Pin

Pin Ibn Battuta / Photo courtesy of ChatGPT (AI Generated)

There comes a moment in certain lives when the soul refuses to stay still. For Ibn Battuta, that moment arrived on a summer morning in 1325, when he was just twenty-one years old. He stood at the edge of Tangier, looking toward Mecca, and something inside him whispered: go. What he thought would be a sacred journey to fulfill his religious duty became something far more profound. It became a conversation with the world itself.

Where did Ibn Battuta travel over the next twenty-nine years? He followed the compass of curiosity rather than the safety of maps. His feet carried him across deserts that shimmered like molten gold, through cities where a hundred languages sang in the marketplaces, and onto seas that both blessed and nearly claimed his life. He walked more than 120,000 kilometers, a distance that circles our planet three times. But numbers alone cannot capture what really happened. This wasn’t just physical movement across geography. It was a spiritual awakening, a scholar’s education in the university of human experience, where every stranger became a teacher and every border was just an invitation to understand more deeply.

Table of Contents

The Beginning of a Sacred Promise

In the medieval world of 1325, leaving home meant something different than it does today. There were no phones to call back, no letters that arrived in days, no certainty you’d ever return. When Ibn Battuta kissed his parents goodbye in Tangier, he was twenty-one and freshly educated as an Islamic scholar and judge. His plan was simple and sacred: join a caravan heading east to perform the Hajj, the pilgrimage every Muslim hopes to make once in their lifetime. The road to Mecca stretched nearly 3,000 miles through North Africa, and young Ibn Battuta traveled it with a group of pilgrims, moving slowly through cities that gleamed white under the African sun. He passed through Tunis, Tripoli, and Alexandria, and each stop awakened something in him that textbooks never could. The world wasn’t just wider than his hometown; it was infinitely more complex and beautiful.

But something shifted in his heart during those first months on the road. The scholar who had spent years studying law and theology in quiet rooms suddenly found himself in the greatest classroom of all: life itself. Every city had its own rhythm, its own way of calling people to prayer, its own flavors in the marketplace. He met merchants who spoke of lands beyond the horizon, Sufi mystics who talked about God in ways that made his soul tremble, and fellow travelers who shared their bread and stories under desert stars. By the time he reached Cairo, the largest city in the Islamic world with nearly half a million people, Ibn Battuta had tasted something intoxicating. It wasn’t just knowledge he was gathering. It was wonder. And wonder, once awakened, doesn’t let you go home easily.

Mecca and the Choice That Changed Everything

Pin

Pin Great Mosque of Mecca / Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

When Ibn Battuta finally arrived in Mecca in 1326, he had already been traveling for over a year. The holy city rose before him like a promise fulfilled, the Kaaba at its center drawing pilgrims from every corner of the Islamic world. He performed the rituals that generations of Muslims had performed before him, circling the sacred structure, drinking from the Zamzam well, standing on the plain of Arafat where the Prophet Muhammad had delivered his final sermon. These were the moments he had dreamed about back in Morocco. This was supposed to be the pinnacle, the turning point where he would head home, satisfied and spiritually renewed. But as he completed his pilgrimage, something unexpected happened. Instead of feeling complete, he felt like he was just beginning to understand how vast and interconnected the world really was. The pilgrims around him came from Persia, from the distant lands of Central Asia, from the kingdoms of India. Each one carried stories of their homelands, and each story was a doorway he wanted to walk through.

So Ibn Battuta made a decision that would define the rest of his life. He wouldn’t go home. Not yet. He would keep moving, keep learning, keep meeting the infinite variations of human culture that God had scattered across the earth. He traveled north to Damascus, a city so beautiful that poets had run out of words trying to describe it. He studied with scholars there, deepening his knowledge of Islamic law, but he also wandered through gardens where fountains sang and roses bloomed in colors he had never seen. Then he turned east toward the lands of Iraq and Persia, visiting Baghdad and the tombs of saints, walking roads where ancient caravans had carried silk and spices for thousands of years. Each place taught him that the world was not divided into “us” and “them” but was instead a tapestry where every thread mattered, where a judge from Morocco could find brotherhood with a merchant from Shiraz, where differences in language and custom only made the underlying unity of human experience more precious.

Into the Heart of Arabia and Beyond

Pin

Pin Image by Talal Alghamdi from Pixabay

After his time in the sophisticated cities of Syria and Iraq, Ibn Battuta felt the pull of Arabia’s deeper mysteries. He journeyed south through the Arabian Peninsula, a landscape where ancient Bedouin tribes still lived as their ancestors had for millennia, moving with their herds across endless expanses of sand and stone. This wasn’t the Arabia of grand mosques and busy markets. This was the raw, elemental desert where survival depended on knowing where the next water source lay hidden beneath the earth. He traveled with caravans that moved like ships across an ocean of dunes, and he learned the hospitality code of the desert people, who would share their last dates with a stranger because in that harsh beauty, kindness was the difference between life and death. The experience stripped away the layers of scholarly abstraction he had built up. Out here, under stars so bright they seemed to whisper secrets, he understood that faith wasn’t just something you studied in books. It was something you lived when you trusted the caravan guide, when you rationed your water, when you helped a fellow traveler whose camel had gone lame.

From Arabia, he sailed down the East African coast, and the world transformed again. The port cities of Somalia and Kenya were cosmopolitan centers where African, Arab, and Persian cultures blended into something entirely new. He visited Mogadishu, where the Sultan’s generosity was legendary, and Mombasa, where the air smelled of cloves and coconut. The Indian Ocean stretched before him like liquid sapphire, and the sailors told him stories of lands even farther south, of the great kingdom of Kilwa where gold from the African interior flowed through markets built of coral stone. Ibn Battuta spent months exploring these coastal communities, marveling at how trade had created a shared language and culture that connected people across thousands of miles of ocean. The jurist in him observed how Islamic law was practiced here with local variations, adapting to customs that predated Islam while maintaining its essential spirit. He was beginning to understand something profound: that human civilization was not a single story but a symphony, with each culture contributing its own voice to a larger harmony.

The Golden Empire of Mali

Pin

Pin Empire of Mali / Photo courtesy of Pennsylvania State University

In 1352, Ibn Battuta set out on one of his most challenging journeys yet: crossing the Sahara Desert to reach the legendary Empire of Mali. Europeans of his time knew almost nothing about the kingdoms south of the great desert, but stories of Mali’s wealth had reached every corner of the Islamic world. This was the realm of Mansa Musa, the emperor who had passed through Cairo decades earlier with so much gold that he accidentally crashed the Egyptian economy. Ibn Battuta joined a massive caravan of merchants and travelers, and for two months they moved across a landscape so hostile that a wrong turn could mean death for everyone. The heat was crushing during the day, the cold bitter at night, and water sources were sometimes a week apart. Yet caravans had been making this journey for centuries, following invisible paths marked by the bones of those who hadn’t made it and the knowledge passed down through generations of guides who could read the desert like others read books.

When he finally reached Mali, Ibn Battuta found an empire that defied every expectation. The capital city of Niani sat on the Niger River, a lifeline that made civilization possible in the midst of harsh savanna. The emperor ruled over a territory larger than Western Europe, and his court was a place of sophisticated protocol and genuine power. Ibn Battuta was impressed by the absolute security he found there—a traveler could cross the empire with gold and valuables without fear of robbery, something he couldn’t say about many places he’d visited. He observed the blend of Islamic practice with local African traditions, noting how people prostrated themselves before the emperor while also maintaining Muslim prayers. The marketplace bustled with goods from across Africa: salt from the desert mines, gold from the southern forests, kola nuts, ivory, and enslaved people being traded in numbers that disturbed him. He spent eight months in Mali, and his accounts would later become one of the few detailed descriptions of this powerful medieval African civilization, preserving details about daily life, governance, and culture that might otherwise have been lost to history.

The Jewel of India and the Sultan's Court

In 1333, Ibn Battuta arrived in Delhi, and his life took a turn he could never have anticipated back in Morocco. India was then ruled by Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq, a ruler whose brilliance and unpredictability made him one of history’s most fascinating and terrifying leaders. The sultan was a scholar who could debate theology and philosophy for hours, but he was also capable of sudden, brutal violence against those he perceived as disloyal. Ibn Battuta impressed the sultan with his legal knowledge and his experience as a jurist, and within weeks of arriving, he was appointed as the qadi, the chief Islamic judge of Delhi. Suddenly, this traveler who had been living out of saddlebags was residing in a palace, receiving a salary that made him wealthy, and presiding over legal cases that affected thousands of people. He married again, as he had in several other places during his travels, adding to the families he was creating across the Islamic world. For eight years, he lived in the intoxicating and dangerous orbit of the sultan’s court, where fortunes could change overnight and yesterday’s favorite could become tomorrow’s prisoner.

But life in Delhi was never comfortable, even with all its luxuries. Ibn Battuta witnessed executions that haunted him, saw political intrigue that made him constantly vigilant, and lived with the knowledge that the sultan’s favor was as unstable as desert sand. He made friends among the Sufi mystics who gathered in the city, finding in their company a spiritual grounding that the material wealth of court life couldn’t provide. The sultan eventually appointed him as an ambassador to China, a mission that would take him even farther from home. Before leaving India, he traveled extensively through the subcontinent, visiting the Malabar Coast where pepper grew in abundance and small kingdoms thrived on maritime trade, and the island of Ceylon where he climbed Adam’s Peak, a mountain sacred to multiple faiths. India had tested him in ways the desert never could, teaching him about power, about the thin line between civilization and chaos, and about how a person could maintain their integrity when surrounded by both magnificence and moral compromise. The judge from Morocco had become a player on one of the world’s great political stages, but the experience left him understanding that worldly success was just another kind of journey, one with its own perils and lessons.

Shipwrecks, Pirates, and the Journey to China

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Freepik

The journey to China that Sultan Muhammad bin Tughluq had arranged for Ibn Battuta turned into one of the most catastrophic episodes of his entire twenty-nine years of travel. He left Delhi in 1341 with a massive diplomatic caravan carrying gifts for the Chinese emperor, including horses, camels, and enslaved people, along with a hundred other companions. But before they even reached the coast, bandits attacked the caravan in the forests of central India. Ibn Battuta was separated from the group, hiding in a mosque while rebels plundered everything the sultan had entrusted to him. When he finally made it to the port city of Calicut on the Malabar Coast, he was essentially starting over, having lost the emperor’s goods and fearing what the unpredictable sultan might do to him if he returned in failure. So he decided to continue toward China anyway, hoping that somehow he could still fulfill his diplomatic mission. He boarded a fleet of Chinese junks, massive wooden ships that dwarfed anything he had seen in the Mediterranean or the Red Sea, with multiple decks and sails that looked like clouds.

Then the sea turned against him with a violence that made all his previous hardships seem gentle. A storm struck the fleet near the Maldive Islands, and Ibn Battuta watched in horror as ships capsized and broke apart, swallowing hundreds of people into the churning waters. He survived by clinging to wreckage and eventually swimming to shore, but he had lost nearly everything again, including companions he had traveled with for years. Rather than give up, he spent time in the Maldives, where he actually served as a judge and married into the local royal family, adding yet another chapter to his already complicated personal life. When he finally continued toward China, sailing through Southeast Asia, he was no longer a grand ambassador but simply a persistent traveler who refused to let disaster stop him. He reached the southern coast of China, visiting the great port cities of Quanzhou and Guangzhou, where he saw ships from all over the world and markets that sold goods he couldn’t even name. But his descriptions of China are briefer and less detailed than his accounts of other places, and some historians wonder if he actually made it as far inland as he claimed, or if the trauma of the shipwrecks had finally exhausted even his remarkable resilience.

The Maldives and the Complexities of Power

Pin

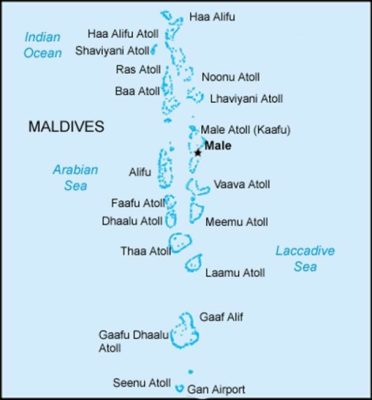

Pin Maldives / Photo courtesy of intercultures.ca

The Maldives became an unexpected home for Ibn Battuta, a place where the traveling judge finally stopped running and settled into a life that was almost ordinary, at least by his extraordinary standards. These islands scattered across the Indian Ocean like emeralds on blue silk were ruled by a sultanate, and the people had converted to Islam relatively recently, just a few centuries before his arrival. Ibn Battuta was welcomed as a learned scholar who could help strengthen Islamic practice and law in the islands, and he accepted a position as the chief qadi once again. For nearly two years, he lived in this tropical paradise, where coconut palms swayed in warm breezes and the ocean provided an abundance of fish.

He married again, this time to a woman from the royal family, and for a moment it seemed he might actually stay somewhere permanently. The islands were beautiful, the people were kind, and his position gave him respect and comfort. But Ibn Battuta was discovering something about himself that he might not have fully understood before: he wasn’t just a traveler by circumstance anymore. He had become a traveler by nature.

What drove him away from the Maldives wasn’t hardship but his own restless spirit and, perhaps, the complications that came with being too close to power. He became involved in local politics, which in a small island sultanate meant navigating family rivalries and court intrigues that made even Delhi seem straightforward. He also clashed with local customs that differed from his more conservative understanding of Islamic practice, particularly regarding women’s dress and behavior in this tropical culture where people had their own long-standing traditions. After trying to impose stricter rules and finding resistance, and after becoming entangled in disputes he couldn’t fully control, he made the familiar choice: he would leave and continue toward China. The pattern of his life had been set. He could settle anywhere, marry, work, and build a life, but something always called him back to the road. Perhaps it was curiosity, or perhaps it was the knowledge that staying in one place meant watching the world grow smaller again, while moving meant keeping alive the sense of infinite possibility that had first seized him as a young man leaving Tangier.

The Return Journey and the Weight of Distance

By 1346, Ibn Battuta had been away from Morocco for more than twenty years. He had crossed oceans, survived storms that killed hundreds, served sultans and emperors, married women whose languages he barely spoke, and witnessed civilizations at heights of glory that would soon fade into history. But something began pulling him homeward, a gravitational force that even his insatiable curiosity couldn’t resist forever. The journey back was not simply retracing his steps. He traveled through Central Asia, passing through the lands of the Mongol khans who ruled over territories so vast that a rider could travel for months and never leave their domain. He visited Samarkand and Bukhara, cities where Islamic scholarship flourished under Mongol protection, and where the architecture seemed to reach toward heaven with turquoise domes that caught the light like pieces of sky. He witnessed the aftermath of the Black Death, the plague that was sweeping across Asia and would soon devastate Europe, leaving entire villages empty and trade routes eerily silent. The world he was returning through was not the same world he had left, and he was not the same man.

When he finally reached the Golden Horde territory north of the Black Sea, he made a detour that took him even farther from home, traveling north into what is now Russia during the brutal winter. He wanted to see the court of the Mongol khan, and he was curious about lands where the cold turned breath into ice crystals and where people lived in ways completely foreign to someone raised under the African sun. He visited Constantinople, the great Byzantine capital where Christian emperors still ruled, and where he observed Orthodox Christianity with the same careful attention he had given to Buddhist temples in India and animist practices in Mali. Every religion, every culture, every way of organizing human life was part of the great tapestry he was documenting in his mind. By the time he turned his face truly homeward, crossing back through Egypt and North Africa, he carried within him a treasury that no caravan could transport: the understanding that humanity was one family with countless expressions, and that the differences between people were never as profound as the fundamental similarities that united them all under the same sky.

Home After Three Decades

In 1349, Ibn Battuta crossed back into Morocco, and the moment his feet touched the soil of his homeland must have carried a weight beyond words. He had left as a twenty-one-year-old student of law, eager and untested. He returned as a man in his mid-forties, weathered by sun and sea, carrying scars from shipwrecks and memories of courts where empires rose and fell. But the homecoming he had imagined for so many years was not waiting for him. His mother had died while he was away, a loss he would never be able to reconcile because he hadn’t been there to say goodbye. His father was also gone. The house he remembered from childhood felt smaller somehow, and the streets of Tangier seemed to belong to a different lifetime. The people he had grown up with had lived entirely different lives while he was gone, marrying, having children, growing old in the same rooms where they were born. They looked at him with a mixture of awe and incomprehension, this man who spoke of Chinese junks and African gold and Indian monsoons as if these were common things. How could he explain what he had seen to people who had never left their own region?

Yet even home couldn’t hold him still for long. Within months, he was traveling again, this time through the parts of North Africa and Spain he had never visited. He crossed into al-Andalus, the Muslim territories in Iberia where Islamic civilization had created architectural wonders like the Alhambra and where libraries held knowledge from three continents. But he could see that this world was shrinking, that Christian kingdoms were gradually reclaiming the peninsula and that the golden age of Muslim Spain was entering its twilight. He returned to Morocco and made one final journey south across the Sahara to visit Mali again, updating his earlier observations and adding new details about the trans-Saharan trade that connected North Africa to the kingdoms of the south. By 1354, when he finally settled in Fez, the capital of Morocco, he was fifty years old and had traveled more than any human being in recorded history up to that point. His wandering days were over, but the real work of his life was just beginning. All those years of movement needed to become something permanent, something that would outlive him and preserve the world he had witnessed.

The Rihla—When Memory Becomes Monument

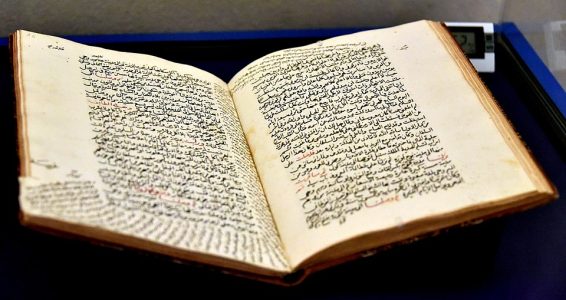

Pin

Pin Rihla Book / Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Sultan of Morocco, Abu Inan Faris, understood that Ibn Battuta carried something invaluable in his memory. This was not just the idle reminiscences of an old traveler but a living archive of the Islamic world at its most expansive moment. The sultan commanded Ibn Battuta to dictate his travels to a young scholar named Ibn Juzayy, and together they began the painstaking work of transforming decades of experience into written form. The book they created, known as the Rihla, which simply means “The Journey,” became one of the most important travel narratives in human history. For months, Ibn Battuta sat with Ibn Juzayy and spoke, pulling from memory the details of places he had seen twenty or thirty years earlier, describing the taste of foods, the layout of cities, the personalities of rulers, the customs of peoples who lived thousands of miles apart. Ibn Juzayy shaped these memories into flowing Arabic prose, sometimes adding his own poetic flourishes and occasionally inserting passages from other sources to fill gaps or add context. The result was not a dry geographical catalog but a deeply human document, full of wonder and fear, judgment and admiration, humor and sorrow.

The Rihla is remarkable not just for where Ibn Battuta went but for how he saw. He paid attention to things that official historians often ignored—how ordinary people lived, what they ate, how they married, what made them laugh. He described the judicial systems of different regions with a professional eye, comparing how Islamic law was interpreted and applied from Morocco to China. He wrote about architecture and agriculture, about the price of bread and the quality of horses, about holy men who performed miracles and charlatans who pretended to. He was honest about his own failures and sometimes inflated his own importance in certain events, a very human tendency that actually makes the account more trustworthy in its imperfection. Some of his stories are clearly exaggerated or borrowed from others, and modern historians debate which parts he truly experienced himself, but even the embellishments tell us something about what people in the fourteenth century found marvelous or important. The Rihla preserved knowledge about societies that would soon be transformed by conquest, plague, and time, offering future generations a window into a world that was interconnected long before globalization became a modern buzzword.

The Legacy That Outlived Empires

Ibn Battuta died sometime around 1368 or 1369 in Morocco, probably in his mid-sixties, which was a respectable age for someone who had survived shipwrecks, diseases, bandit attacks, and the countless dangers of medieval travel. He spent his final years living quietly, perhaps serving as a judge in some local capacity, far from the grand courts and exotic lands that had defined most of his adult life. History doesn’t record much about these last years, which is fitting in a way. The man who had been so restless, so hungry for the next horizon, finally found peace in stillness. But while his body came to rest in Moroccan soil, his spirit continued traveling through the words of the Rihla, which began circulating among scholars and educated readers across the Islamic world. For centuries, his book was read primarily in Arabic, known mainly to those who could access manuscript copies in libraries and madrasas. European scholars didn’t discover it until the nineteenth century, when they began translating it and realizing that this medieval Muslim traveler had documented parts of Africa and Asia that Europeans were only beginning to explore.

Today, Ibn Battuta stands as a bridge figure in human history, someone who lived in a world that was deeply connected despite lacking our modern technology. He showed that curiosity could be a form of worship, that learning about other people’s ways of life didn’t diminish your own faith but deepened it. His travels remind us that globalization is not a new phenomenon but something humans have been building for millennia through trade routes, diplomatic missions, scholarly exchanges, and individual wanderers who refused to believe that their birthplace was the only place worth knowing. The Rihla remains a vital historical source for understanding medieval Africa, Asia, and the Islamic world, offering details about daily life, economics, politics, and culture that appear nowhere else. More than that, it’s a testament to what one person can accomplish when they choose openness over fear, when they treat every encounter as an opportunity to learn rather than to judge. Ibn Battuta’s greatest journey wasn’t measured in kilometers but in the expansion of understanding, both his own and ours, proving that the most important discoveries happen not just in the places we go but in what those places teach us about being human.

FAQs

Most historians believe he did cover this remarkable distance over 29 years, though some details in his account may be exaggerated or secondhand. His core journeys are well-documented.

He worked as an Islamic judge in various courts, received gifts from rulers he visited, married into wealthy families, and traveled with merchant caravans who valued having a legal scholar along.

In the Islamic world, yes. He traveled farther and documented more societies. Marco Polo became more famous in Europe, but Ibn Battuta’s Rihla is considered more comprehensive by historians today.

He was fluent in Arabic and likely knew Persian. He probably picked up basic phrases in other languages during his travels, and often relied on translators in places like China and Mali.

Yes! Many sites he described still exist, including Mecca, Damascus, Delhi, Timbuktu, and Mombasa, though they’ve changed significantly. Some countries even have “Ibn Battuta routes” for tourists to follow.