Pin

Pin Image by @earlystartupdays / Instagram

In 1989, Japan ruled the economic world. Tokyo real estate was worth more than all of California combined. Eight of the world’s ten largest companies were Japanese. The country’s GDP per capita had surpassed America’s, and everyone was talking about the “Japanese miracle.”

Then everything collapsed. What followed wasn’t just a recession—it was three decades of economic stagnation that economists now call Japan’s “Lost Decades.” The story of how the world’s second-largest economy fell so far offers crucial lessons about what happens when rapid growth meets poor policy decisions, cultural resistance to change, and demographic reality.

Table of Contents

America Rebuilt Japan — Then Regretted It

After World War II, Japan lay in ruins. Cities were destroyed, industries were shattered, and the country faced an uncertain future. The United States, fearing the spread of communism in Asia, made a strategic decision that would reshape global economics. They pumped massive aid into Japan, broke up monopolies, and helped rebuild the nation into an export powerhouse.

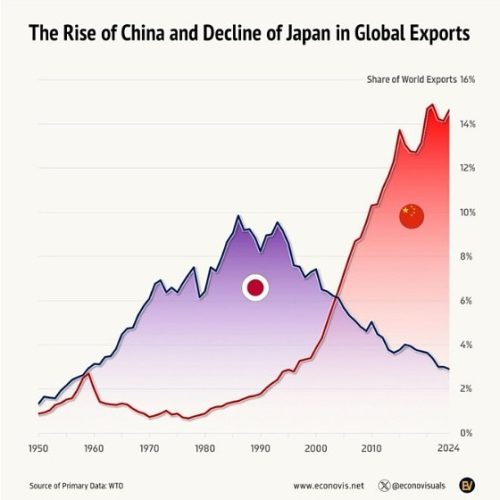

The transformation was remarkable. Japan’s exports grew an astounding 380% between 1953 and 1970, making it the greatest economic comeback story in modern history. Japanese companies mastered quality manufacturing, creating products that the world desperately wanted. Cars, televisions, radios, and semiconductors bearing the “Made in Japan” label became symbols of reliability and innovation. What started as American strategy to contain communism had created an economic rival that would soon challenge America’s dominance.

Pin

Pin Japan Became the World's Factory

By the 1980s, Japan had evolved into something unprecedented—a global manufacturing powerhouse that seemed unstoppable. Cars, televisions, radios, and semiconductors rolled off Japanese assembly lines with a precision that amazed the world. The secret wasn’t just hard work; it was Japan’s revolutionary approach to quality management systems that emphasized continuous improvement and collective responsibility.

The numbers were staggering. By the 1980s, eight of the world’s ten largest companies were Japanese. Tokyo had become the center of global finance, and Japan’s GDP per capita had actually surpassed America’s. The phrase “Made in Japan” had transformed from a post-war joke about cheap goods into a gold standard of quality. Japanese business practices, from just-in-time manufacturing to total quality management, became case studies in business schools worldwide. The student had become the master, and the world was taking notes.

Pin

Pin The Plaza Accord - The Deal That Broke Everything

Pin

Pin In 1985, representatives from five major economies gathered at the Plaza Hotel in New York City to address America’s growing trade deficit. The solution seemed straightforward: Japan would allow its currency, the yen, to strengthen against the dollar, making Japanese exports more expensive and American goods more competitive. Japan, eager to maintain good relations with its most important ally, agreed to the deal.

The consequences were devastating and immediate. The yen doubled in value over just three years, crushing Japan’s export-driven economy. Companies that had built their success on selling affordable, high-quality goods to the world suddenly found their products priced out of international markets. Growth stalled, exports collapsed, and panic set in. The very foundation of Japan’s economic miracle—its ability to manufacture and sell to the world—had been severely damaged by a single policy decision made in a Manhattan hotel room.

Cheap Money Flooded the Country

Pin

Pin Image from Economist

Desperate to save their economy after the Plaza Accord disaster, Japanese policymakers made a fateful decision: they slashed interest rates to 2.5% in an attempt to stimulate growth. The move was designed to encourage investment and spending, but it had an unintended consequence that would haunt Japan for decades. Cheap money began flooding the country, but instead of flowing into productive business investments, it poured into speculation.

Real estate and stock prices began climbing at alarming rates. People stopped investing in companies and started betting on land instead. The bubble grew so massive that at its peak, the Imperial Palace grounds in Tokyo were theoretically worth more than the entire state of California. Banks, flush with easy money, made increasingly risky loans to fuel the frenzy. What Japan had intended as economic medicine had become economic poison, creating the largest asset bubble in modern history.

The Bubble Burst — And Never Recovered

Pin

Pin Source: Wikipedia.org

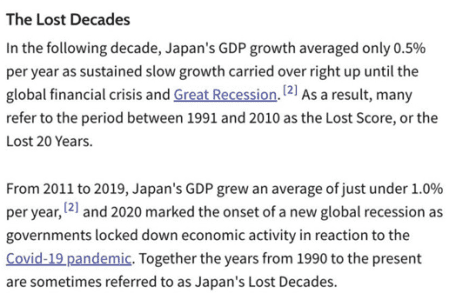

By 1990, reality came crashing down. The stock market lost $1 trillion in value, real estate prices plummeted by $3 trillion, and wages peaked at levels they still haven’t recovered to in 2024. What had taken decades to build was destroyed in a matter of months. The bursting of Japan’s asset bubble marked the beginning of what economists would later call the “Lost Decades” — a period of economic stagnation that continues to this day.

The psychological impact was as devastating as the financial one. A generation of Japanese workers who had known only growth and prosperity suddenly faced a new reality of flat wages and limited opportunities. The period between 1991 and 2010 saw Japan’s GDP grow at an average of just 0.5% per year. Even during the recovery period from 2011 to 2019, growth averaged under 1% annually. The country that had once seemed destined to overtake America economically was now struggling just to maintain what it had.

Zombie Banks Made It Worse

Pin

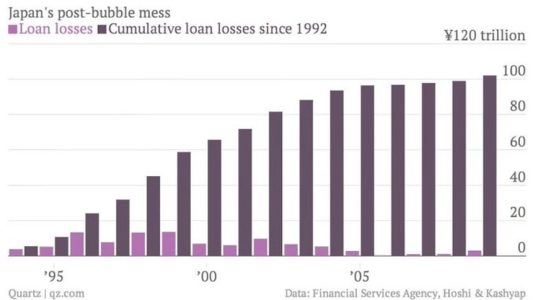

Pin While the bubble was bursting, Japan’s banking system faced a crisis that would prolong the economic pain for decades. Banks had made massive loans during the bubble years, much of it to companies and real estate projects that were now worthless. The smart move would have been to write off these bad debts, let failing companies go bankrupt, and start fresh. Instead, Japanese banks chose a different path that would haunt the economy for years.

The government bailed out the banks without forcing them to clean up their balance sheets first. This created what economists call “zombie banks” — financial institutions that were technically alive but couldn’t fulfill their main purpose of funding growth. These zombie banks kept lending money to “zombie companies” that should have been allowed to fail. Innovation died, competition stagnated, and resources that could have funded new, dynamic businesses were tied up keeping dead companies on life support. The chart showing cumulative loan losses climbing to over 100 trillion yen tells the story of a financial system that refused to face reality.

Stimulus Came Too Late, and Was Spent Wrong

When Japan finally decided to fight back against its economic decline, the government launched massive stimulus spending programs. The theory was sound: inject money into the economy to boost demand and create jobs. But the execution was deeply flawed. Instead of investing in cities and emerging industries that could drive future growth, Japan poured billions into rural infrastructure projects that did little to move the economic needle.

Keynesian economists had offered several explanations for Japan’s struggles, including Paul Krugman’s theory that the country was caught in a “liquidity trap” where consumers hoarded savings because they feared worse times ahead. The government’s response was to build bridges to nowhere, rural roads that served few people, and other projects that felt more like political favors than economic planning. Much of the stimulus spending seemed designed to reward loyal constituencies rather than address the structural problems holding back Japan’s economy. The money was there, but it was flowing in all the wrong directions.

Culture Blocked Progress

In Japan, success still means long hours and seniority. While other countries adapted to the new global economy with flexible work arrangements, entrepreneurial risk-taking, and rapid innovation, Japan remained locked in cultural patterns that had served it well during its manufacturing heyday but became obstacles in the information age. Efficiency, innovation, and risk-taking all took a backseat to “doing things the way they’ve always been done.”

The image of exhausted businessmen sleeping on trains became a symbol of Japanese dedication, but it also revealed a deeper problem. Japan even has a word for working to death: “karoshi.” This cultural resistance to change made it nearly impossible to build the future with a mindset rooted in the past. Companies clung to hierarchical structures where age mattered more than ideas, and lifetime employment practices that discouraged both worker mobility and corporate restructuring. The very cultural traits that had made Japan an industrial powerhouse were now suffocating its ability to innovate and adapt.

No Immigration = Shrinking Population

While other developed countries faced aging populations by bringing in workers, Japan made a different choice. The country essentially closed its borders to immigration, maintaining one of the world’s most restrictive immigration policies. This decision, rooted in cultural preferences for homogeneity, would have devastating long-term consequences for the economy. The population data tells a stark story: what had once been steady growth turned into decline.

Today, over 25% of Japan’s population is above 65 years old, and young people aren’t having children at replacement rates. The workforce has been shrinking since 1995, creating a vicious cycle where fewer workers must support more retirees while also trying to drive economic growth. The chart showing Japan’s population change reveals the dramatic shift: the bars that once reached high into positive territory now sit below the zero line. Without fresh workers to fill jobs, drive consumption, and support innovation, Japan’s economy became trapped in a demographic death spiral that no amount of monetary policy could fix.

The Real Lesson - Debt Isn't Free

Innovation matters more than most politicians realize, and Japan forgot some key economic truths that would prove costly. The lesson that emerged after decades of stagnation was simple but painful: land doesn’t equal wealth, bailouts don’t equal growth, all businesses need to die eventually, and governments can’t accurately predict the future. These hard truths became evident as Japan struggled to restart its economic engine despite throwing money at the problem for years.

The formal photo of Japanese officials in their traditional morning dress tells the story of a country still clinging to old ways of doing business. While other nations embraced creative destruction – allowing failing companies to collapse so new ones could take their place – Japan tried to preserve everything. The result was an economy weighed down by zombie companies that consumed resources without generating innovation. The government’s attempts to pick winners and losers, fund infrastructure projects based on political considerations rather than economic merit, and maintain the status quo all contributed to Japan’s extended economic malaise.

Japan’s Crisis Holds Lessons for the World

Japan’s struggle wasn’t just a local tragedy — it was a global warning. The collapse of its “economic miracle” showed how even the strongest economies can crumble when structural issues are ignored and policy mistakes pile up. The combination of an aging society, resistance to reform, speculative bubbles, and political short-termism created a perfect storm that turned prosperity into stagnation.

Other nations should pay attention. China, for example, faces a similar mix of high debt, shrinking demographics, and reliance on exports. The U.S. continues to run on ballooning debt and asset inflation that echoes Japan’s pre-1990 bubble. Europe faces its own struggles with aging populations and rigid labor systems. Japan proves that no amount of wealth or prestige makes a country immune to long-term decline if leaders fail to adapt.

The “Lost Decades” were not inevitable. They were the product of choices—bad policy, cultural rigidity, and demographic neglect. Japan’s crisis is less about the past than it is about the future, offering a mirror that every nation must decide whether to look into, or ignore at its own peril.

FAQs

The Plaza Accord of 1985 and the resulting asset bubble were the main triggers. Cheap money policies, reckless real estate speculation, and a stock market frenzy created an unsustainable bubble that burst in the early 1990s, wiping out trillions in wealth.

Unlike the U.S., Japan avoided letting bad banks and failing companies collapse. Instead, it propped them up, creating “zombie banks” and “zombie companies” that drained resources and stalled innovation for decades.

Japan’s refusal to open its borders to immigration, combined with one of the world’s lowest birth rates, meant its workforce started shrinking while the elderly population kept growing. This imbalance created long-term economic drag.

Yes. Japan’s rigid work culture, obsession with seniority, and resistance to restructuring made it difficult to adapt. Traits that worked well in the manufacturing boom became obstacles in the knowledge and tech-driven global economy.

That debt-fueled growth has limits, speculative bubbles eventually burst, and demographics cannot be ignored. Countries must embrace innovation, allow creative destruction, and adapt policies before structural problems become permanent crises.