Pin

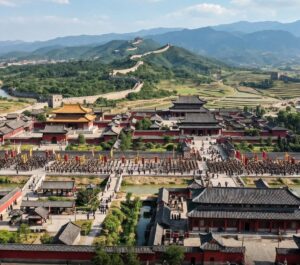

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Synopsis: America scattered sixty-three national parks across her landscape like a gambler tossing cards on a table, each one a different kind of winning hand. These places hold the sort of beauty that makes a person reconsider their life choices, the kind of wilderness that reminds you how small your problems really are. Understanding what each park offers saves you from the common mistake of visiting the wrong one at the wrong time with the wrong expectations.

The United States government made a decision back in the 1800s that still puzzles real estate developers today—they set aside vast stretches of perfectly good land and declared nobody could build strip malls on it. This act of restraint, rare among governments then and now, created the national park system that protects sixty-three of the most spectacular landscapes on the continent.

These parks range from Alaskan wilderness so remote you need a bush plane just to see it, to desert valleys hot enough to make the Devil himself complain about the weather. Some parks preserve forests where trees were already ancient when Columbus got lost looking for India. Others protect coral reefs, volcanic calderas, or slot canyons so narrow you have to turn sideways to squeeze through.

Table of Contents

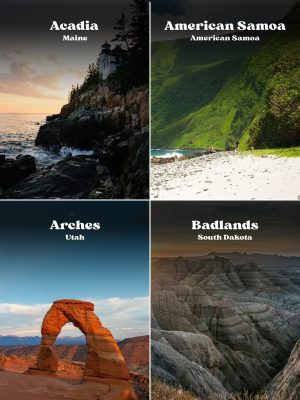

Acadia, American Samoa, Arches, and Badlands

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Acadia perches on Maine’s rocky coast where the mountains meet the Atlantic in a collision that’s been going on since the glaciers retreated. That lighthouse at Bass Harbor Head has been warning ships away from the rocks since 1858, though the real danger is falling in love with this place so hard you can’t bring yourself to leave. The 63 National Parks in USA include only one in the northeastern states, which makes Acadia something of a geographical oddity among parks that tend to cluster out West.

American Samoa sits six thousand miles southwest of California, making it the park that requires the most commitment to visit. Those green volcanic peaks rising straight out of the South Pacific aren’t just scenery, they’re part of the only national park south of the equator. The coral reefs surrounding these islands contain fish species found nowhere else on Earth, swimming in waters so clear you can see a hundred feet down without squinting.

Arches in Utah showcases what happens when erosion works on sandstone for a few million years with artistic intent. Delicate Arch has become so famous that Utah slapped it on their license plates, though the two thousand other stone arches in the park deserve equal billing. Standing beneath these natural sculptures at sunset, when the rock glows orange-red against a darkening sky, you understand why ancient peoples considered these formations sacred.

Badlands in South Dakota earned its name honestly from the Lakota who called it “mako sica,” meaning land bad, which tells you how welcoming they found this terrain. Those layered rock formations rising from the prairie look like a massive cake that somebody left out in the weather for sixty million years. The striations in the rock tell the story of an ancient sea, then a subtropical forest, then the slow patient work of wind and water carving away everything soft until only these pinnacles remained standing.

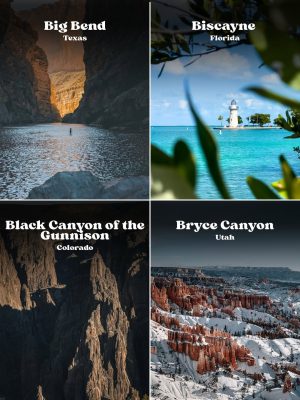

Big Bend, Biscayne, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, and Bryce Canyon

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Big Bend occupies the great curve where the Rio Grande changes its mind about which direction it wants to flow through Texas. The park protects eight hundred thousand acres of Chihuahuan Desert, plus mountains, plus river canyons, which gives you three distinct ecosystems for the price of one admission. Santa Elena Canyon cuts through limestone cliffs that rise fifteen hundred feet on either side of the river, creating shadows so deep that noon feels like evening.

Biscayne down in Florida protects what most folks never see, ninety-five percent of the park sitting underwater where coral reefs, seagrass beds, and mangrove forests create nurseries for fish that eventually stock the entire Atlantic. That lighthouse on the keys stands as one of the few structures in a park dedicated to proving that emptiness has value. Glass-bottom boat tours here reveal a world that makes tropical aquariums look understocked.

Black Canyon of the Gunnison in Colorado earned its name from walls so steep and narrow that sunlight only reaches the bottom for thirty-three minutes a day. The Gunnison River spent two million years cutting through Precambrian rock, the ancient stuff that forms the basement of continents, creating a gorge so sheer that early surveyors refused to believe their measurements. Standing at the rim looking down two thousand feet of vertical cliff makes your survival instincts scream at you to back away slowly.

Bryce Canyon isn’t actually a canyon, which would irritate geological purists if they weren’t too busy staring at the hoodoos. These rock spires cluster in natural amphitheaters like an audience waiting for a performance that never starts, their orange and white stripes catching sunrise in ways that make photographers weep with joy. Frost wedging created these formations, water seeping into cracks, freezing, expanding, and breaking off chunks of limestone in a process that continues every winter night.

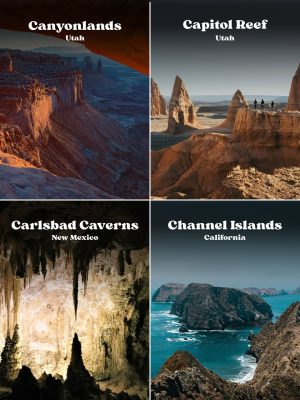

Canyonlands, Capitol Reef, Carlsbad Caverns, and Channel Islands

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Canyonlands in Utah shows what the Colorado and Green Rivers accomplished when given enough time and erosion potential. The park divides into four districts separated by these rivers, each one offering a different flavor of desert wilderness. Mesa Arch frames the sunrise so perfectly that photographers camp overnight to claim their spot, though the arch itself is more remarkable for what it reveals than what it is, a window onto canyons that drop away into depths that make your stomach flip.

Capitol Reef preserves a hundred-mile wrinkle in the Earth’s crust called the Waterpocket Fold, which sounds technical until you see these massive rock layers tilted up like a book someone left spine-up on a table. Mormon settlers named it Capitol Reef because the white sandstone domes reminded them of the Capitol building, and the rock formations blocked travel like an ocean reef blocks ships. The orchards they planted still produce fruit that visitors can pick during harvest season, assuming you believe in mixing your geology with agriculture.

Carlsbad Caverns in New Mexico descends into darkness so complete that your eyes never adjust no matter how long you wait. The Big Room spreads out larger than six football fields, with ceiling heights that could swallow a thirty-story building without touching the roof. Every evening during summer months, four hundred thousand Brazilian free-tailed bats spiral out of the cave entrance in a tornado of wings, heading out to eat their body weight in insects before dawn sends them back underground.

Channel Islands off the California coast protect five islands that evolution used as a laboratory for creating unique species. Island foxes here shrunk to the size of house cats, while island scrub jays grew larger and bluer than their mainland cousins. The kelp forests surrounding these islands grow so thick that swimming through them feels like flying through an underwater redwood forest, sunlight filtering down through the canopy in golden shafts.

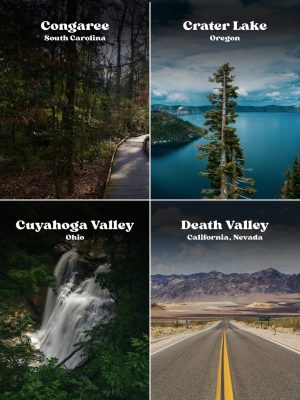

Congaree, Crater Lake, Cuyahoga Valley, and Death Valley

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Congaree in South Carolina protects the largest intact expanse of old-growth bottomland hardwood forest in North America, which is a fancy way of saying these trees grow in a swamp and nobody cut them down yet. The boardwalk trail lets you walk among bald cypresses and water tupelos without getting your feet wet, though the mosquitoes consider that boardwalk a buffet line with you as the main course. Spring flooding transforms this forest into a mirror world where trees stand in their own reflections.

Crater Lake in Oregon fills a volcanic caldera with water so blue it looks photoshopped even when you’re standing right there staring at it. Mount Mazama exploded seven thousand years ago with such violence that it emptied its magma chamber and collapsed into itself, creating a bowl that filled with rain and snowmelt over the centuries. At nearly two thousand feet deep, this ranks as the deepest lake in America, and the absence of any inlet streams means the water achieves a clarity and color found almost nowhere else on Earth.

Cuyahoga Valley in Ohio proves that national parks don’t all require towering mountains or endless deserts. This park protects the river valley between Cleveland and Akron, a green corridor that somehow survived the Industrial Revolution happening on both ends. The river itself caught fire so many times from industrial pollution that it inspired the Clean Water Act, though these days the water runs clean enough that beavers have moved back in and built dams without checking the property values first.

Death Valley in California and Nevada holds the record for hottest temperature ever reliably recorded on Earth at one hundred thirty-four degrees Fahrenheit, measured at Furnace Creek in 1913. The valley sits two hundred eighty-two feet below sea level at Badwater Basin, the lowest point in North America, where salt flats stretch to the horizon in geometric patterns that form when water evaporates and leaves minerals behind. Those rare occasions when rain does fall here trigger wildflower blooms that transform the valley into a garden that vanishes again within weeks.

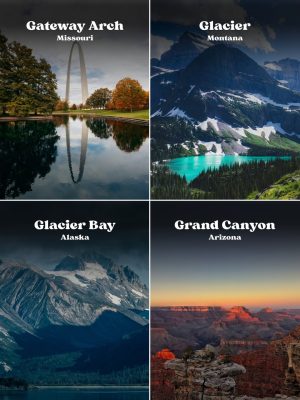

Gateway Arch, Glacier, Glacier Bay, and Grand Canyon

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Gateway Arch in Missouri became a national park in 2018, which makes it the newest addition to the collection though the arch itself has been standing since 1965. This six hundred thirty-foot stainless steel curve commemorates westward expansion, serving as a bookmark between the settled East and the frontier West. Riding the tram to the top involves sitting in a small pod that travels up the inside of the arch like a very slow roller coaster, depositing you at an observation deck where you can see for miles while trying not to think about being suspended inside a hollow monument.

Glacier in Montana earns its name from the handful of glaciers still clinging to the highest peaks, though climate change is melting them faster than anyone wants to admit. Going-to-the-Sun Road crosses the Continental Divide while somehow staying attached to cliff faces that seem too steep for roads, offering views that make passengers grab the dashboard and question their life choices. Grizzly bears here outnumber rangers, which creates interesting dynamics for hikers who forgot to bring bear spray.

Glacier Bay in Alaska shows what happens when ice retreats and life rushes in to fill the empty space. When Captain George Vancouver sailed through here in 1794, he found a wall of ice five miles wide and four thousand feet thick blocking the bay. That ice has retreated sixty-five miles since then, exposing rock that’s seeing daylight for the first time in thousands of years. Humpback whales feed in these waters during summer, their breaches and tail slaps echoing off glaciers that still calve icebergs the size of buildings into the sea.

Grand Canyon in Arizona needs no introduction, though most visitors still gasp when they first see it because photographs cannot capture the scale of this hole in the ground. The Colorado River spent six million years cutting through layer after layer of rock, exposing nearly two billion years of Earth’s history in the canyon walls. Standing at the rim, you’re looking at a timeline written in stone, each layer representing a different chapter of this planet’s story, and your entire human existence amounts to less than a footnote.

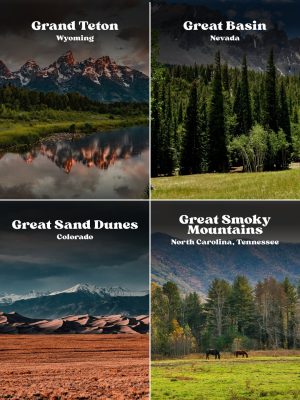

Grand Teton, Great Basin, Great Sand Dunes, and Great Smoky Mountains

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Grand Teton in Wyoming rises from the valley floor with no foothills to soften the drama, just jagged peaks shooting straight up like stone teeth trying to bite the sky. The Snake River reflects these mountains on calm mornings, creating the image that launched a thousand postcards and convinced Ansel Adams he’d chosen the right career. Moose wade through wetlands here with an indifference to humans that suggests they haven’t checked the food chain lately.

Great Basin in Nevada protects the transition zone between desert and alpine forest, where bristlecone pines grow at elevations that would kill most trees. Some of these gnarled ancients have been alive for five thousand years, which means they were already old when the Egyptians were building pyramids. Lehman Caves beneath the park contain formations that took millions of years to create, stalactites and stalagmites meeting in columns that water built one mineral deposit at a time.

Great Sand Dunes in Colorado pile seven hundred fifty feet high against the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, creating the tallest dunes in North America through a quirk of geography that funnels sand into this corner of the valley. These dunes sing when conditions are right, the sand grains sliding against each other in frequencies that create low humming sounds. Medano Creek flows along the base of the dunes each spring, appearing and disappearing based on snowmelt from the mountains, offering the surreal sight of a beach with fourteen-thousand-foot peaks as a backdrop.

Great Smoky Mountains straddling North Carolina and Tennessee attracts more visitors than any other national park, which tells you something about accessibility and beauty combining into irresistible appeal. The morning fog that gives these mountains their name rolls through valleys like slow-motion waterfalls, condensation from forests so dense they create their own weather. This park protects more than a hundred species of trees, more diversity than exists in all of northern Europe, plus synchronous fireflies that flash in unison during June nights in a mating display that looks like Christmas lights achieved consciousness.

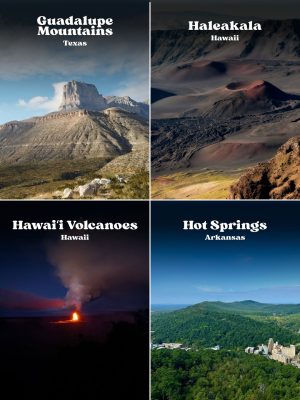

Guadalupe Mountains, Haleakalā, Hawai'i Volcanoes, and Hot Springs

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Guadalupe Mountains in Texas protect an ancient reef from the Permian period when this part of Texas sat at the bottom of a tropical sea. El Capitan rises from the desert like a limestone ship’s prow, the reef’s southern edge marking where the sea once stopped. McKittrick Canyon in autumn displays fall colors that seem impossible in West Texas, maples and oaks turning gold and red in a microclimate that gets just enough moisture to support trees that shouldn’t exist in the Chihuahuan Desert.

Haleakalā on Maui means “house of the sun” in Hawaiian, named for the summit crater where the demigod Māui supposedly lassoed the sun to slow its journey across the sky. The volcano rises ten thousand feet from sea level, though it actually starts on the ocean floor, making it one of the tallest mountains on Earth when measured from base to summit. Sunrise from the summit attracts crowds who drive up in darkness, watching stars fade as the sun breaks over clouds that float below like an ocean of cotton.

Hawai’i Volcanoes on the Big Island showcase creation in real time as Kīlauea continues adding land to the island through lava flows that reach the sea in steam explosions. The park lets you walk across recent lava flows, black rock still warm underfoot, and peer into Halema’uma’u Crater where molten rock glows red beneath a vent to the planet’s interior. This is geology without the comfortable distance of time, volcanic activity happening on human timescales instead of millions of years.

Hot Springs in Arkansas became a national park before the Park Service even existed, protected since 1832 because people believed the thermal waters held medicinal properties. Forty-seven springs flow from Hot Springs Mountain, carrying water that fell as rain four thousand years ago, heated by the Earth’s interior, and filtered through rock before emerging at one hundred forty-three degrees. Bathhouse Row preserves ornate buildings where visitors once “took the waters,” though these days most folks just appreciate the architecture and wonder who thought sitting in hot water could cure tuberculosis.

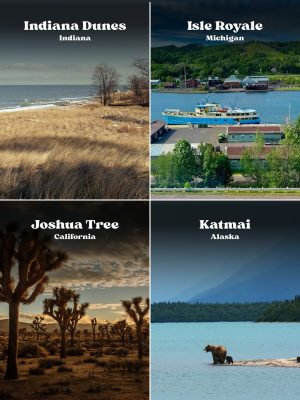

Indiana Dunes, Isle Royale, Joshua Tree, and Katmai

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Indiana Dunes along Lake Michigan became a national park in 2019, protecting sand dunes that reach heights of two hundred feet and contain more plant diversity than any other park in the National Park System. These dunes migrate inland pushed by winds off the lake, burying forests that sometimes re-emerge decades later like wooden ghosts. The park sits close enough to Chicago that you can see the skyline from the beach, an odd juxtaposition of wilderness and civilization sharing the same horizon.

Isle Royale floats in Lake Superior as a wilderness island that closes entirely during winter when ice makes access impossible. The island hosts one of the longest-running predator-prey studies in science, tracking the relationship between wolves and moose since 1958. These days the wolf population hovers near extinction after inbreeding weakened the pack, while moose numbers fluctuate based on how much vegetation they can eat before starving themselves out of house and home.

Joshua Tree in California protects the quirky yucca trees that only grow where the Mojave and Colorado deserts overlap. These twisted sentinels depend on a single species of moth for pollination, a relationship so specific that if one disappears, the other follows into extinction. Rock climbers love this park for the granite formations that offer thousands of routes, while stargazers appreciate the dark skies that reveal the Milky Way in all its glory.

Katmai in Alaska exists primarily because of bears, specifically brown bears that gather at Brooks Falls each July to catch salmon jumping upstream to spawn. The falls create a buffet line where bears position themselves in the best fishing spots, occasionally catching salmon in mid-air like furry baseball players fielding fly balls. This park protects the largest population of brown bears on Earth, roughly two thousand of them, which makes hiking here an exercise in paying very close attention to your surroundings.

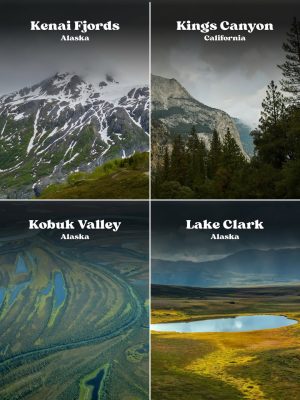

Kenai Fjords, Kings Canyon, Kobuk Valley, and Lake Clark

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Kenai Fjords in Alaska showcases glaciers that flow from the Harding Icefield down to the sea, calving icebergs in thunderous crashes that echo across the water. The fjords themselves were carved by ice age glaciers that retreated, leaving behind steep-walled valleys that flooded when sea levels rose. Boat tours here navigate between icebergs while orcas hunt seals and sea otters float on their backs cracking open sea urchins against their chests like they’re picnicking at a salad bar.

Kings Canyon in California pairs with Sequoia as a joint park protecting groves of giant sequoias plus a canyon that rivals Yosemite for sheer granite walls. The Kings River carved a canyon eight thousand feet deep in places, creating what John Muir called “a rival to Yosemite” though fewer people visit because the road ends halfway in and the rest requires hiking. General Grant tree stands as the nation’s Christmas tree by congressional decree, though the tree itself remains indifferent to this honor.

Kobuk Valley in Alaska protects sand dunes that seem wildly out of place twenty-five miles north of the Arctic Circle. These dunes rise a hundred feet high, remnants of glacial deposits that wind shaped into formations that wouldn’t look out of place in the Sahara. Caribou migrate through here twice annually, half a million animals moving in herds that stretch to the horizon, following routes their ancestors established millennia ago through landscape that hasn’t changed much since the ice retreated.

Lake Clark in Alaska offers the usual Alaskan attractions of bears, salmon, volcanoes, and coastline, plus accessibility that requires a floatplane because roads gave up trying to reach this corner of the state. Two active volcanoes anchor the landscape, steam rising from their peaks like signals that the Earth’s interior remains very much awake. The lake itself runs forty miles long, fed by glaciers and drained by rivers where red salmon return each summer to spawn and feed the bears waiting in the shallows.

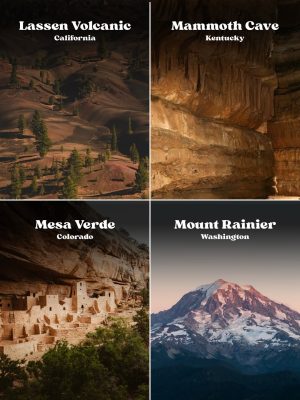

Lassen Volcanic, Mammoth Cave, Mesa Verde, and Mount Rainier

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Lassen Volcanic in California serves as the southern end of the Cascade Range volcanic chain, protecting a landscape still recovering from the mountain’s last eruption in 1915. Bumpass Hell offers a walk through a geothermal area where boiling mud pots, fumaroles, and sulfur vents prove that volcanic activity continues beneath the surface. The park’s hydrothermal areas showcase all four types of volcanoes in one place, making this a geology classroom where the lessons involve avoiding scalding water and toxic gas.

Mammoth Cave in Kentucky contains more than four hundred miles of surveyed passages, making it the longest cave system known to exist on Earth. The cave keeps revealing new sections as explorers find passages previously missed, suggesting the final length might exceed six hundred miles of tunnels carved by water dissolving limestone over millions of years. Historic tours follow routes that enslaved people first explored in the early 1800s, mapping passages by torchlight and discovering chambers that remain among the cave’s most impressive features.

Mesa Verde in Colorado preserves cliff dwellings built by Ancestral Puebloans between 600 and 1300 AD, stone structures tucked into alcoves like apartments carved into canyon walls. Cliff Palace contains one hundred fifty rooms, though nobody lives there anymore, the inhabitants having abandoned these dwellings around 1300 for reasons that archaeologists still debate. Walking through these ruins raises questions that archaeology can’t fully answer about why people would build such elaborate structures only to leave them behind.

Mount Rainier in Washington looms over Seattle like a massive monument visible from a hundred miles away on clear days. The mountain rises fourteen thousand four hundred feet, an active volcano wearing twenty-six glaciers like a frozen cloak. Paradise area lives up to its name with wildflower meadows that bloom in summer, offering views of the mountain that make you understand why so many people attempt to climb it despite the avalanches, crevasses, and storms that kill climbers with depressing regularity.

New River Gorge, North Cascades, Olympic, and Petrified Forest

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

New River Gorge in West Virginia became a national park in 2020, protecting a river that flows north and happens to be one of the oldest rivers on the continent despite its misleading name. The gorge cuts through the Appalachian Plateau creating whitewater that rafters consider some of the best in the eastern United States. That massive steel arch bridge spanning the gorge rises eight hundred seventy-six feet above the river, allowing cars to cross in seconds a gap that used to require an hour’s detour through the valley.

North Cascades in Washington contains more than three hundred glaciers, which is more than half of all glaciers in the lower forty-eight states packed into one park. The mountains here rise in jagged peaks that early explorers called the American Alps, with names like Mount Terror and Mount Fury suggesting that somebody had strong opinions about the climbing conditions. This park sees fewer visitors than almost any other in the continental United States, which tells you something about how far people will drive for accessibility versus scenery.

Olympic in Washington offers three parks in one, combining Pacific coastline, temperate rainforest, and alpine peaks into an ecosystem collection that shouldn’t logically exist in the same place. The Hoh Rainforest receives over twelve feet of rain annually, creating forests so thick with moss and ferns that walking through them feels like stepping into a Tolkien novel. The coastal section protects seventy miles of wilderness beach where tide pools reveal ecosystems that exist in the space between land and sea, creatures timing their lives to the rhythm of waves.

Petrified Forest in Arizona protects logs that turned to stone over millions of years when volcanic ash buried trees and silica-rich water replaced wood cells with quartz crystal. These fossilized logs scatter across badlands painted in layers of purple, blue, and red, minerals creating colors that look too vivid to be natural. The park also contains the largest concentration of petroglyphs in the Southwest, ancient rock art that raises questions about what these images meant to the people who carved them and whether we’re interpreting their messages correctly.

Pinnacles, Redwood, Rocky Mountain, and Saguaro

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Pinnacles in California protects volcanic rock formations that originated two hundred miles south and traveled north along the San Andreas Fault over twenty-three million years. The rock spires create technical climbing routes that attract climbers willing to share the cliffs with California condors that nest in caves within the formations. Talus caves form where massive boulders fell and wedged together, creating passages that stay cool enough to harbor colonies of Townsend’s big-eared bats.

Redwood in California guards the tallest trees on Earth, coast redwoods that regularly exceed three hundred feet and live for two thousand years or more. Walking among these giants recalibrates your sense of scale, the trees so massive that looking up makes you dizzy trying to see the tops. The foggy coast provides these trees with moisture they absorb through their needles, a survival adaptation that lets them thrive in climates that would kill lesser species.

Rocky Mountain in Colorado offers alpine tundra within easy reach of Denver, making it one of the most accessible high-elevation parks in the system. Trail Ridge Road crosses the Continental Divide at twelve thousand feet, a route that closes every winter when snow makes passage impossible even for plows. Elk gather in massive herds during autumn rut, the bulls bugling challenges that echo across meadows as they compete for breeding rights.

Saguaro in Arizona exists solely to protect those iconic cacti you recognize from Road Runner cartoons. These giants grow nowhere else except the Sonoran Desert, taking seventy-five years to grow their first arm and living up to two hundred years if nothing kills them first. The cacti bloom white flowers in late spring, a brief show that happens at night when temperatures drop enough that the flowers won’t desiccate before dawn.

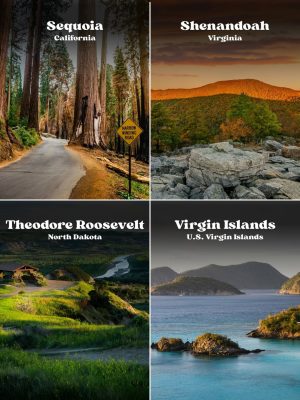

Sequoia, Shenandoah, Theodore Roosevelt, and Virgin Islands

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Sequoia in California protects the largest trees by volume on Earth, giant sequoias that dwarf even their redwood cousins. General Sherman tree contains enough wood to build a house for every person in a small town, standing two hundred seventy-five feet tall with a base that measures over a hundred feet around. These trees depend on fire to reproduce, their cones requiring heat to open and release seeds onto mineral soil that fire prepares for germination.

Shenandoah in Virginia offers Appalachian wilderness within easy reach of Washington DC, making it the park where politicians go when they suddenly remember that nature exists. Skyline Drive runs the length of the park along the Blue Ridge crest, offering overlooks where autumn foliage creates color displays that make New England jealous. Black bears here have learned that picnic baskets contain food, proving that Yogi Bear based his career on legitimate research.

Theodore Roosevelt in North Dakota preserves badlands that inspired the future president’s conservation ethic after he came here to ranch following his wife’s death. The Little Missouri River carved canyons through layers of sediment and volcanic ash, creating striped formations that change color depending on light conditions. Bison, elk, and wild horses roam these badlands much as they did when Roosevelt rode these same hills, hunting and writing about experiences that shaped his environmental policies.

Virgin Islands in the Caribbean protects coral reefs, tropical forests, and beaches that colonial powers fought over for centuries. Trunk Bay offers an underwater snorkel trail with plaques identifying reef features, making this the closest thing to a guided tour you can take while swimming with sea turtles. The park covers two-thirds of St. John island, protected after Laurance Rockefeller purchased the land and donated it to the Park Service in 1956, a gift that preserved one of the last undeveloped Caribbean islands.

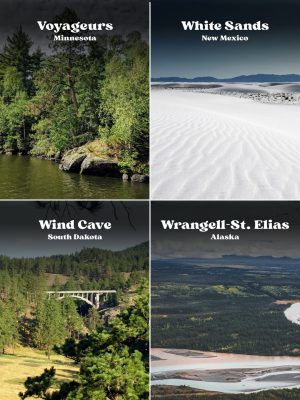

Voyageurs, White Sands, Wind Cave, and Wrangell-St. Elias

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Voyageurs in Minnesota takes its name from French-Canadian fur traders who paddled canoes through these waterways, following routes that indigenous peoples established centuries earlier. The park consists largely of interconnected lakes, meaning boats provide better access than cars for reaching most destinations. Northern lights dance over these waters during winter, auroras reflecting off ice in displays that justify the brutal cold temperatures required to witness them.

White Sands in New Mexico contains the largest gypsum dune field in the world, brilliant white sand that reflects sunlight so intensely that sunglasses become mandatory equipment. The dunes migrate across the basin pushed by prevailing winds, swallowing anything in their path before eventually exposing it again as they move on. The white sand stays cool enough to walk barefoot even in summer because gypsum doesn’t absorb heat like silica sand, making this the rare desert where you can play in the sand without burning your feet.

Wind Cave in South Dakota holds ninety-five percent of the world’s known boxwork formations, calcite fins that protrude from cave walls in honeycomb patterns that make no logical sense until you understand the chemistry that created them. The cave also contains the seventh longest cave system in the world, with new passages still being discovered and mapped. Above ground, the park protects mixed-grass prairie where bison herds graze alongside prairie dogs that built towns covering hundreds of acres before humans decided prairie dogs were agricultural pests worth eliminating.

Wrangell-St. Elias in Alaska covers more area than Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Switzerland combined, making it the largest national park in the United States by a margin that makes other parks look like city parks in comparison. Nine of the sixteen highest peaks in the United States rise within park boundaries, ice-covered mountains that challenged early climbers and continue killing people who underestimate the dangers of Alaskan alpine environments. Glaciers here measure in miles rather than feet, rivers of ice flowing down valleys at speeds that seem imperceptible until you compare photographs taken years apart.

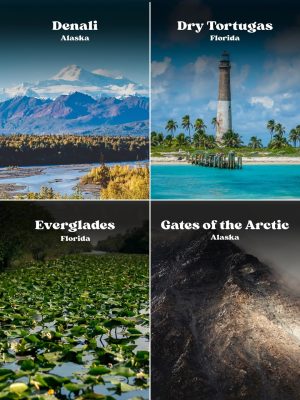

Denali, Dry Tortugas, Everglades, and Gates of the Arctic

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Denali in Alaska protects North America’s tallest peak, a mountain so massive that it creates its own weather systems and hides behind clouds roughly two-thirds of the time. The mountain rises twenty thousand three hundred ten feet from a base elevation of about two thousand feet, making the vertical relief greater than Mount Everest when you account for Everest starting at seventeen thousand feet. Denali means “the great one” in the native Koyukon language, which seems more accurate than McKinley, the name some politician slapped on it in 1896 without bothering to ask the people who’d been looking at this mountain for thousands of years.

Dry Tortugas sits seventy miles west of Key West in the Gulf of Mexico, accessible only by boat or seaplane, which keeps the crowds manageable and the water impossibly clear. Fort Jefferson occupies most of Garden Key, a massive brick fortress that never fired a shot in anger but served admirably as a prison for Union deserters during the Civil War. The snorkeling here rivals anything in the Caribbean, coral reefs and shipwrecks creating underwater landscapes where sea turtles glide past with the casual grace of creatures that know they own the place.

Everglades in Florida protects the largest subtropical wilderness in North America, a river of grass flowing so slowly toward the Gulf of Mexico that it barely seems to move at all. This isn’t a swamp despite what most people think—it’s a shallow, wide river fifty miles across and a hundred miles long, moving at a quarter mile per day through sawgrass prairies. Alligators here treat the park like their personal kingdom, sunning on banks and occasionally reminding visitors that Florida’s ecosystem includes apex predators with better claims to the real estate than humans have.

Gates of the Arctic in Alaska sits entirely above the Arctic Circle, the second-largest national park in the system and arguably the most remote. No roads lead here, no trails get maintained, and no park facilities exist beyond a handful of ranger stations. This park attracts people who think Denali has gotten too crowded, which tells you everything about the level of wilderness involved. The Brooks Range cuts through the park, mountains rising from tundra in formations that haven’t changed much since the last ice age ended and the glaciers retreated north.

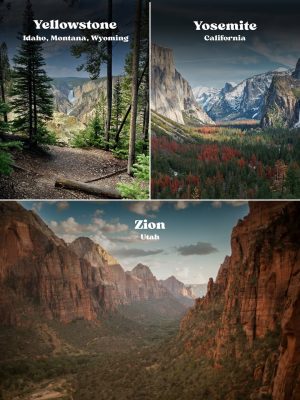

Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Zion

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy The Great Planet

Yellowstone sits atop a volcanic hotspot that produces enough geothermal energy to power every geyser, hot spring, and mud pot in the park while still having enough left over to threaten civilization if the caldera ever decides to erupt again. Scientists monitor earthquake activity here with the nervous attention of people sitting on a geological time bomb, knowing that the supervolcano erupts roughly every six hundred thousand years and the last eruption happened six hundred forty thousand years ago. The math on that timeline makes geologists uncomfortable, though they’re quick to point out that volcanic systems don’t follow schedules.

Yosemite Valley carved by glaciers and refined by the Merced River creates a granite cathedral where El Capitan and Half Dome serve as pillars holding up the sky. Yosemite Falls drops twenty-four hundred feet in three sections, the longest waterfall in North America when measured from top to bottom. John Muir spent years wandering these mountains, writing descriptions that convinced Congress to establish the park, though he never managed to capture in words what your eyes see when you first enter the valley and everything stops making sense for a moment.

Zion in Utah offers slot canyons so narrow that walking through them requires turning sideways in places where the walls rise a thousand feet but stand only a few feet apart. The Virgin River carved these canyons through Navajo sandstone, the same formation that creates the white and pink cliffs throughout the park. Angels Landing trail includes sections where chains bolted into rock provide the only thing preventing hikers from falling hundreds of feet, making this the hike where people discover whether they actually have a fear of heights or just a healthy respect for gravity.

Why Some States Have More Parks Than Others

Alaska, California, and Utah dominate the national park count not because they’re better at lobbying Congress but because geology dealt them winning hands. Alaska’s size and remoteness preserved landscapes that development destroyed elsewhere, while California’s topographical diversity crammed multiple climate zones into one state. Utah’s canyon country contains so many unique geological features that five national parks barely scratch the surface of what deserves protection.

The eastern states have fewer national parks largely because European settlement started there, meaning more land got converted to farms, cities, and industry before anyone thought preservation might matter. The parks that do exist in the East, like Acadia and Shenandoah, required buying back land from private owners and allowing forests to regrow over abandoned farms. This process costs more and takes longer than simply drawing boundaries around existing wilderness.

Political factors also influence which areas become national parks versus national monuments or other protected designations. Presidents can declare national monuments without congressional approval, while parks require legislation that must navigate committee hearings, amendments, and the general dysfunction that characterizes Congress. Some areas wait decades for park status, existing as monuments until political conditions align and Congress finally acts.

Planning Your National Park Adventures

Visiting all sixty-three national parks requires more planning than just buying a Golden Age pass and pointing your car west. Alaska and Hawaii require flights, winter closes roads to many parks, and summer crowds at popular destinations like Yellowstone and Yosemite can make you question whether wilderness means what you thought it meant. The shoulder seasons of spring and fall offer better odds of experiencing these places without fighting for parking spaces or sharing trails with tour groups.

Remote parks demand different preparation than the accessible ones. Gates of the Arctic requires wilderness skills that Acadia doesn’t, while American Samoa needs vaccinations and passports that Rocky Mountain doesn’t. Each park has specific challenges, whether that’s altitude sickness at high elevation parks, heat exhaustion in desert parks, or bear encounters in Alaska. Researching conditions before you visit prevents the kind of mistakes that rangers spend their summers rescuing people from making.

The national park system represents the best idea America ever had, protecting landscapes and ecosystems for reasons beyond profit or development. These places exist because enough people decided that some things shouldn’t be turned into shopping malls or subdivisions, that wilderness has value beyond what can be extracted or built. Whether you visit one park or all sixty-three, these protected areas offer reminders that humans don’t actually run this planet, we just live here on terms that nature occasionally allows.

FAQs

Gates of the Arctic in Alaska wins this contest, sitting entirely above the Arctic Circle with no roads leading in, no trails maintained, and no facilities once you arrive. Getting there requires a bush plane and a wilderness permit that basically says “you’re on your own.”

Gates of the Arctic sees fewer than 10,000 visitors per year, mostly because reaching it requires serious money, wilderness skills, and a comfort level with being genuinely alone that most people don’t possess. Lake Clark runs a close second for similar reasons.

Several people have done it, though the logistics require military precision, a substantial budget for flights to Alaska and Hawaii, and enough vacation time to make your employer question your commitment. Winter closures make timing crucial for parks like Glacier and Rocky Mountain.

Katmai in Alaska hosts the largest concentration of brown bears on Earth, roughly 2,200 of them, though they’re generally more interested in salmon than tourists. Yellowstone combines grizzlies, wolves, and bison that gore more people than bears do because visitors treat them like petting zoo animals.

Some parks now require timed entry reservations during peak season—Glacier, Rocky Mountain, Arches, and Yosemite all implemented systems to control crowds. Others operate first-come, first-served, which means arriving at dawn or accepting that parking lots fill by 9 AM during summer.