Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Chikage Takeuchi (竹内千景)

Walk through any quiet street in Kyoto, and you might spot a small workshop where someone is carefully folding fabric into tiny flower petals. Or perhaps you’ll find a craftsman painting delicate patterns onto glass, one precise cut at a time. These aren’t just hobbies or tourist attractions. They’re living connections to Japan’s soul.

The country has always honored the beauty of things made slowly, thoughtfully, and by hand. While the world rushes forward, these hand-made crafts in Japan remain anchored in tradition, yet somehow feel more relevant than ever. Each piece carries the fingerprints of its maker and whispers of generations past.

What makes these crafts so special isn’t just their beauty. It’s the philosophy behind them: that imperfection can be elegant, that patience creates value, and that some things should never be rushed. Let’s explore fifteen of these remarkable traditions that continue to shape Japanese culture today.

Table of Contents

1. Wagasa

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Freepik

The wagasa isn’t just something to keep you dry. It’s a statement of elegance that has graced tea ceremonies, kabuki stages, and geisha districts for hundreds of years. Made entirely by hand using bamboo ribs, handmade washi paper, and natural oils, each umbrella takes days or even weeks to complete.

What sets wagasa apart is the care in every step. Craftsmen split bamboo into perfectly thin strips, then arrange them in a radial pattern that opens like a flower. The paper is painted with traditional designs—cherry blossoms, waves, or geometric patterns—then coated with linseed or perilla oil to repel water. The result glows softly when light passes through it.

Today, only a handful of workshops still make wagasa the traditional way. You’ll see them carried in festivals, used as props in traditional dance, or displayed as art pieces. They cost more than modern umbrellas, sure, but they carry something priceless: the knowledge that someone poured their skill and patience into creating something beautiful just for you. 🌸

2. Kintsugi

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Six Senses Vana

When a cherished ceramic bowl breaks, most people throw it away. In Japan, they see an opportunity. Kintsugi is the practice of mending broken pottery with lacquer mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. The repair doesn’t hide the damage—it celebrates it, turning cracks into veins of precious metal.

The philosophy runs deep here. Instead of treating breakage as failure, kintsugi embraces it as part of the object’s history. Those golden seams tell a story: this bowl fell, it survived, and now it’s more beautiful than before. The technique requires steady hands and patience, as multiple layers of lacquer must cure between applications.

You’ll find kintsugi pieces in museums and modern homes alike. Some collectors actually seek out repaired ceramics, valuing them more than perfect ones. It’s a gentle reminder that our flaws and scars don’t diminish us. They make us unique, resilient, and yes, sometimes even more beautiful than we were before. ✨

3. Washi Paper

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Voyapon

Washi isn’t just paper. It’s a material that has held Japanese writing, art, and architecture together for over a thousand years. Made from the inner bark of mulberry trees, gampi, or mitsumata plants, washi is stronger and more durable than most modern paper despite feeling delicate to the touch.

The process is meditative and physical. Craftspeople soak and steam the bark, then beat it into pulp by hand. They pour this mixture onto bamboo screens, letting water drain through while fibers interlock naturally. The sheets dry slowly, resulting in paper that can last centuries without yellowing or crumbling. You’ll find it in everything from lanterns that cast warm, diffused light to shoji screens that divide rooms with translucent beauty.

UNESCO recognized washi-making as an Intangible Cultural Heritage, and for good reason. This craft connects modern Japan to its past while remaining useful today. Artists still use it for calligraphy and printmaking. Designers incorporate it into notebooks and home décor. Each sheet carries the texture of human hands and the quiet wisdom of a process that refuses to be rushed. 📜

4. Nishijin Ori

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Knife Rolls

In the Nishijin district of Kyoto, looms have been clicking and clacking for over five hundred years. Nishijin ori refers to the luxurious silk textiles woven here, often incorporating gold and silver threads into patterns so intricate they can take months to complete. These fabrics become the most exquisite kimonos, obi belts, and ceremonial garments in Japan.

The weaving process demands both technical skill and artistic vision. Weavers work from detailed pattern charts, sometimes lifting individual threads by hand to create complex designs. The fabrics shimmer with scenes from nature: cranes in flight, autumn leaves, flowing water. Each color must be perfectly aligned, each thread tension precisely controlled. One small mistake can ruin weeks of work.

Nishijin ori represents the pinnacle of textile artistry, but it also faces modern challenges. Fewer young people want to spend years mastering such demanding work. Yet the workshops that remain produce textiles so breathtaking that collectors worldwide treasure them. When you see someone wearing a formal kimono with elaborate patterns that seem to dance in the light, there’s a good chance it came from these historic looms. 🎎

5. Arita & Imari Porcelain

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Noorie’s Vintage

The small towns of Arita and Imari in Saga Prefecture have been producing some of the world’s finest porcelain for over four hundred years. What started when Korean potters discovered kaolin clay deposits in the area eventually became Japan’s first porcelain industry. Today, Arita-yaki and Imari-yaki ceramics are prized globally for their delicate hand-painted designs and remarkable durability.

The creation process blends chemistry with artistry. Potters shape the pure white porcelain on wheels, then fire it at extremely high temperatures that few other clays can withstand. After this initial firing, artists paint intricate patterns using mineral-based pigments, often featuring blue cobalt designs of flowers, landscapes, or traditional motifs. A final glaze firing locks these paintings beneath a glass-like surface that can last generations.

What makes these pieces special isn’t just their technical perfection. It’s the way each painter brings their own touch to traditional patterns, keeping designs fresh while honoring centuries of style. You might find a rice bowl with tiny flowers painted around its rim, or a vase depicting a mountain scene so detailed you could study it for hours. These aren’t mass-produced items. They’re functional art that transforms everyday meals into moments of quiet appreciation. 🍵

6. Edo Kiriko

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of MASU

Edo kiriko emerged in Tokyo during the late 1800s when Japanese artisans adapted European glass-cutting techniques into something uniquely their own. The craft involves taking clear or colored crystal glass and carving intricate geometric patterns into its surface using rotating grinding wheels. The result catches light like a prism, scattering rainbows across nearby surfaces while maintaining sharp, precise edges that feel almost impossibly clean.

Creating these pieces requires extraordinary control and years of practice. The artisan holds the glass against spinning diamond or stone wheels at exact angles, cutting grooves that intersect to form elaborate patterns. Traditional designs include hemp leaf motifs, fishnet patterns, and chrysanthemum flowers, each requiring different cutting techniques and depths. One slip can ruin hours of work, so craftsmen develop an almost meditative focus as they work.

You’ll find edo kiriko in everything from whiskey glasses that transform your evening drink into a light show, to decorative vases that look like frozen fireworks. The craft nearly disappeared after World War II, but dedicated masters kept it alive. Now it’s experiencing a revival as people rediscover the pleasure of drinking from a glass that was shaped entirely by human hands and patience. Each piece refracts not just light, but the spirit of craftsmanship itself. ✨

7. Sashiko

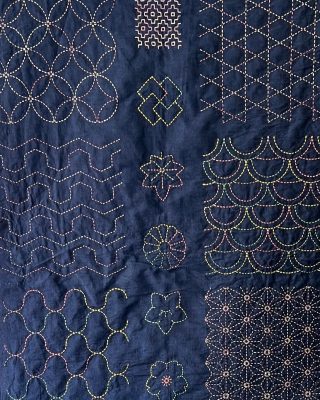

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Kitealo

Sashiko started not as decoration, but as necessity. Centuries ago, Japanese farmers and fishermen couldn’t afford to throw away worn clothing, so they reinforced thin fabric with running stitches that held layers together. Over time, these functional repairs evolved into an art form featuring geometric patterns stitched in white thread against indigo cloth. The name itself means “little stabs,” referring to the simple up-and-down motion of the needle.

The beauty of sashiko lies in its humble origins and meditative rhythm. Stitchers work by hand, following traditional patterns like waves, mountains, or interlocking circles. Each stitch should be the same length, creating a visual harmony that’s both calming to create and pleasing to view. The repetitive motion becomes almost therapeutic, connecting modern practitioners to generations of people who sat by lamplight, mending clothes while their hands moved in steady patterns.

Today, sashiko has traveled far beyond its repair origins. Fashion designers incorporate it into jackets and bags. Quilters use the technique to add texture and meaning to their work. Home crafters stitch sashiko patterns onto pillows and wall hangings. What makes it endure isn’t just its beauty, but its accessibility. Anyone with a needle, thread, and patience can practice this craft, joining a tradition that values simple tools and steady effort over expensive materials. 🧵

8. Tsumami Zaiku

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of COCON

Tsumami zaiku is the art of creating flowers from tiny squares of silk fabric, each piece folded with tweezers into petals no bigger than a fingernail. This delicate craft emerged during the Edo period when artisans needed decorative elements for the elaborate hairpins worn with formal kimonos. The technique involves cutting silk into small squares, folding each one into a petal shape, then gluing dozens or even hundreds of these petals together to form realistic flowers like cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, or peonies.

The precision required borders on the microscopic. Craftspeople use specialized tweezers to fold each fabric square, applying rice starch paste to hold the shape. The petals must be uniform in size and angle, or the final flower looks unbalanced. A single hairpin ornament might contain over a hundred individual petals, each folded and placed by hand. The process demands not just skill but genuine devotion to detail that most people can barely comprehend.

These fabric flowers appear on traditional hair accessories called kanzashi, which geishas and brides wear during special occasions. Modern artisans have expanded the craft into brooches, earrings, and decorative art pieces. Despite its painstaking nature, tsumami zaiku continues to attract practitioners who find something deeply satisfying in transforming flat fabric into three-dimensional beauty, one tiny fold at a time. 🌸

9. Daruma Dolls

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Donna Aurora G.

The daruma doll is one of Japan’s most recognizable folk crafts, with its round red body, thick eyebrows, and distinctively blank eyes. These papier-mâché dolls represent Bodhidharma, the founder of Zen Buddhism, who according to legend meditated so long that his arms and legs fell off. But the dolls serve a purpose beyond decoration. They’re vessels for goals and determination, blank canvases waiting for your ambitions to bring them to life.

When you buy a daruma, both eyes are unpainted white circles. You paint in one eye while setting a goal or making a wish, leaving the second eye blank. The one-eyed doll sits somewhere visible, silently reminding you of your commitment. Only after achieving your goal do you paint the second eye, completing the doll and honoring the journey. If the year ends without success, many people take their daruma to temples for ceremonial burning, then start fresh with a new one.

Craftspeople in cities like Takasaki have been making these dolls by hand for generations. They build up layers of papier-mâché over wooden molds, let them dry, then paint the distinctive red bodies and facial features. The weighted bottom means the doll always rights itself when knocked over, embodying the Japanese proverb about falling down seven times and getting up eight. It’s a simple craft with profound meaning, turning determination into something you can hold in your hands. 🎯

10. Kokeshi Dolls

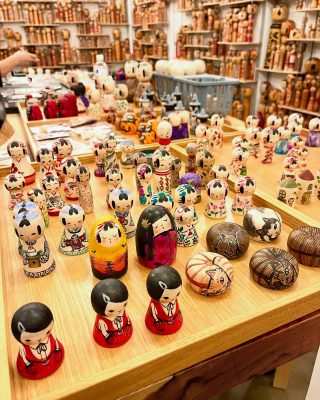

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Shibuya Kokeshi

Kokeshi dolls are charmingly minimalist wooden figures that originated in the hot spring regions of northern Japan during the Edo period. These hand-carved dolls have no arms or legs, just a cylindrical body topped with a round head, yet their simplicity creates an almost magnetic appeal. Craftspeople turn them on lathes from a single piece of wood, usually mizuki or dogwood, then hand-paint their faces and decorative patterns using thin brushes and natural pigments.

What strikes most people first is their sweet, almost shy expressions. The faces typically feature just a few delicate lines: closed or slightly open eyes, a small red mouth, and sometimes rosy cheeks. The bodies display painted floral patterns, geometric designs, or colorful stripes that vary by region and maker. Each area of northern Japan developed its own kokeshi style, so collectors can often identify where a doll was made just by looking at its proportions and decoration.

Originally sold as souvenirs to travelers visiting hot springs, kokeshi have become beloved collectibles worldwide. Some people display entire collections, appreciating how each doll captures a moment of the maker’s artistic vision. Modern artisans continue the tradition while occasionally adding contemporary touches, but the essence remains unchanged. These quiet wooden figures remind us that beauty doesn’t require complexity, and sometimes the simplest forms speak most directly to the heart. 🪆

11. Lacquerware

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Vintage by Dani

Lacquerware, known as urushi in Japan, transforms everyday objects into glossy treasures that can last centuries. The craft relies on sap harvested from lacquer trees, a substance that hardens into an incredibly durable, waterproof finish when exposed to humidity. Artisans apply this natural resin in multiple thin layers to wooden bowls, trays, chopsticks, and decorative pieces, building up depth and richness that synthetic finishes simply cannot replicate.

The process tests patience in ways few other crafts do. Each layer of lacquer must dry completely in a humid chamber before the next application, and a single piece might receive anywhere from ten to over a hundred coats depending on its intended quality. Between layers, craftspeople polish the surface until it’s perfectly smooth, removing any dust particles or imperfections. Some pieces take months or even years to complete, with the final result being a lustrous surface so deep it almost seems to glow from within.

What makes lacquerware special goes beyond its beauty. The finish actually grows stronger and more beautiful with age and use. Oil from human hands gradually enriches the surface, adding warmth and character over decades. You’ll find lacquerware in traditional tea ceremonies, high-end restaurants, and family heirlooms passed down through generations. It’s a craft that literally improves with time, rewarding patience with objects that your great-grandchildren might still be using. ✨

12. Samurai Sword

Pin

Pin Image by skefalacca from Pixabay

The Japanese sword, or nihontō, represents perhaps the most revered metalworking tradition in the world. Master swordsmiths, who must train for years before earning certification, forge these blades using techniques that have remained essentially unchanged for over a thousand years. The process begins with tamahagane, a special steel made from iron sand smelted in traditional clay furnaces. This isn’t just metalwork—it’s considered a sacred art form with Shinto rituals performed at various stages.

Creating a single blade can take several months of intense, focused labor. The smith repeatedly heats, folds, and hammers the steel, sometimes performing this process dozens of times to create thousands of microscopic layers. This folding removes impurities and creates the blade’s distinctive wavy pattern. The smith then shapes the curve and edge, applies a special clay mixture to different parts of the blade, and performs a critical heat treatment that gives the cutting edge its legendary hardness while keeping the spine flexible enough to absorb impact.

Today, only a few hundred licensed swordsmiths work in Japan, and they can only produce a limited number of blades per year by law to preserve quality. These aren’t weapons for battle anymore—they’re works of art that collectors and museums treasure. Each sword carries the spirit of its maker, embodying values like discipline, perfection, and the belief that some things are worth doing the hardest possible way because the result transcends mere function. ⚔️

13. Bamboo Craft

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Japanese Crafts

Bamboo has shaped Japanese life for millennia, and the craft of takesaiku transforms this fast-growing grass into objects of remarkable beauty and utility. Artisans select bamboo carefully based on age, flexibility, and intended use, then split the thick stalks into thin strips that can be woven, bent, and shaped. The material’s natural strength and flexibility make it perfect for everything from tea ceremony utensils to intricate baskets that seem impossibly delicate yet hold their shape for decades.

The weaving techniques vary widely depending on the region and the object being created. Some craftspeople use tight, dense weaves for baskets meant to carry heavy items, while others create open, airy patterns for decorative pieces or flower arrangements. The bamboo must be worked while still somewhat green and pliable, requiring artisans to move quickly and decisively. As it dries, the bamboo locks into its new shape, hardening into a form that resists water and wear far better than most people expect from what looks like thin strips of grass.

What draws people to bamboo craft is its connection to the natural world and Japanese aesthetics of simplicity. A well-made bamboo basket embodies the concept of using just enough material and no more, creating beauty through restraint rather than excess. Tea masters prize bamboo utensils for their humble elegance. Modern designers incorporate bamboo weaving into furniture and lighting. The craft endures because bamboo grows abundantly and sustainably, and skilled hands can coax it into forms that feel both ancient and perfectly suited to contemporary life. 🎋

14. Tenugui Dyeing

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Ponpindo

Tenugui are thin cotton towels that have been part of Japanese daily life for centuries, serving as everything from hand towels to headbands, gift wrapping, and decorative wall hangings. What makes them special isn’t just their versatility, but the traditional hand-dyeing techniques used to create their distinctive patterns and colors. The most prized tenugui are dyed using methods like chusen, where craftspeople pour dye through stencils onto stacked layers of fabric, creating patterns that penetrate all the way through the cloth rather than just sitting on the surface.

The dyeing process requires remarkable skill and timing. Artisans prepare rice paste resist patterns or use paper stencils to block certain areas from absorbing dye. They must work quickly because the dye begins setting immediately, and any hesitation or uneven application shows in the final product. Traditional designs include seasonal motifs like cherry blossoms or autumn leaves, geometric patterns, festival imagery, or playful illustrations. The edges are left unhemmed and naturally fray slightly with use, which Japanese aesthetics consider part of the cloth’s honest character rather than a flaw.

Tenugui occupy a sweet spot between functional and artistic. You can actually use them daily for drying hands or wiping sweat, yet they’re beautiful enough to frame and display. Many people collect them as affordable souvenirs that capture specific moments, places, or seasons. The cloth becomes softer and more absorbent with each washing, aging gracefully rather than deteriorating. It’s a craft that honors the idea that everyday objects deserve beauty, and that things we touch regularly should bring small moments of joy. 🎨

15. Bonsai Art

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Zimmer Bonsai

Bonsai is the art of cultivating miniature trees that capture the essence and beauty of their full-sized counterparts in nature. This isn’t simply growing small plants in pots—it’s a living art form that can span generations, with some bonsai trees being hundreds of years old and passed down through families. Practitioners carefully shape these trees through precise pruning, wiring, and root management, guiding growth over years or decades to achieve forms that evoke windswept mountain pines, ancient forest giants, or graceful willows by a stream.

The practice demands a unique relationship with time that few other crafts require. You can’t rush a bonsai into maturity. Each cut, each wire placement, each decision about which branch to keep affects not just this season but years into the future. Enthusiasts learn to read their trees, understanding when they need water, when to fertilize, when the branches are flexible enough to wire into new positions. The trees respond slowly, sometimes taking months to reveal whether your intervention succeeded or needs correction. This creates a dialogue between human and nature that unfolds at nature’s pace.

What makes bonsai profound is how it compresses vast landscapes into small spaces without losing their spirit. A tree that fits on a table can still convey the dignity of a centuries-old pine clinging to a mountainside. The practice teaches patience, attention, and respect for natural processes. Modern practitioners around the world have embraced bonsai, but Japan remains its spiritual home, where masters continue refining techniques and philosophies that see trees not as possessions but as living partners in creation. 🌳

FAQs

Each piece takes days, weeks, or months to complete by hand. You’re paying for a master’s lifetime of skill, rare materials, and the time investment that modern factories simply can’t replicate. Plus, many techniques use natural materials that must be harvested sustainably. 💰

Absolutely! Many workshops offer hands-on experiences where you can try your hand at making washi paper, painting kokeshi dolls, or attempting basic bamboo weaving. It’s a wonderful way to appreciate the skill involved and take home something you made yourself. 🎨

Yes, though the numbers are smaller than previous generations. Some crafts face succession challenges, but there’s growing interest as people seek meaningful work and connection to heritage. Several programs now support apprenticeships in traditional arts. 👨🎨

Look for slight variations that show human touch, certifications from craft associations, and higher price points reflecting labor costs. Reputable shops provide maker information. True handmade items have subtle irregularities that machine-made products lack. ✨

Sashiko embroidery is wonderfully accessible—you only need fabric, needle, and thread. Origami and basic kokeshi painting are also beginner-friendly. These crafts teach fundamental Japanese aesthetic principles while being forgiving to newcomers. 🧵