Pin

Pin Courtesy of Cheese from Scratch

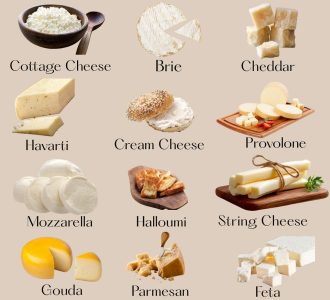

Synopsis: Now here’s a subject that deserves our full attention—cheese, in all its bewildering variety. This catalog presents twenty-five distinct specimens of this ancient food, each one possessing its own curious character and purpose. You’ll learn what separates a young cheese from an old one, why some melt beautifully while others stubbornly refuse, and which varieties belong on your dinner table versus your dessert plate. The information here aims to transform you from a confused spectator at the cheese counter into a confident selector who knows exactly what they want. By the end, you’ll understand these dairy creations well enough to choose them wisely and enjoy them properly.

Humanity has been making cheese for at least four thousand years, though nobody kept particularly good records in the early days. What we do know is this: someone discovered that milk, when treated just right, becomes something far more interesting than it started out being. That discovery has fed countless generations and sparked fierce regional pride in places that take their cheese-making seriously.

The trouble with cheese today is that there’s too much of it, or rather, too many kinds of it. Walk into any respectable grocery store and you’ll face a dairy case that stretches halfway to next Tuesday, filled with wheels and blocks and wedges that all look vaguely similar but taste nothing alike. Some folks just grab whatever’s on sale and hope for the best. Others stand there looking perplexed, wondering why anyone needs seventeen varieties of white cheese when surely three or four would suffice.

But here’s the truth that makes this whole business worthwhile: each type of cheese exists because it solves a particular problem or satisfies a specific craving. The soft ones spread nicely on bread. The hard ones grate beautifully over pasta. The stinky ones make you feel sophisticated at dinner parties. Once you understand what each variety does best, the whole confusing mess starts making sense, and you can navigate that cheese counter with the confidence of someone who knows their business.

Table of Contents

1. Mozzarella

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Quesarella

Mozzarella represents the entry point for most people’s cheese education, and for good reason. This mild, white cheese originated in Italy, where folks made it fresh daily and ate it while it still held the warmth of its creation. The texture feels soft and slightly springy, like something that hasn’t quite made up its mind about being solid yet.

What makes mozzarella special is its talent for melting. When heat hits this cheese, it transforms into long, stretchy strings that make pizza and lasagna worth eating. Fresh mozzarella, sold in balls floating in brine, tastes entirely different from the low-moisture version you find shredded in bags. The fresh kind belongs in salads with tomatoes and basil, where its delicate milk flavor won’t get bullied by stronger ingredients.

You can make mozzarella at home in about thirty minutes if you’re feeling ambitious, though most sensible people just buy it. The cheese gets its characteristic texture from a process called pasta filata, which involves stretching the warm curds like taffy until they develop that familiar squeaky bite. When you need cheese that melts without getting greasy, mozzarella does the job better than just about anything else.

2. Cheddar

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Pixabay

Cheddar has become so common that people forget it once meant something specific. This cheese came from the English village of Cheddar, where limestone caves provided perfect aging conditions. Real cheddar gets its character from a process called cheddaring, where cheese makers stack and turn the curds repeatedly to develop that dense, slightly crumbly texture we recognize.

The flavor of cheddar depends entirely on how long it aged. Young cheddar, aged just a few months, tastes mild and creamy, suitable for people who get nervous around assertive flavors. Medium cheddar has more personality, with a sharper bite that announces itself without shouting. Extra sharp cheddar, aged a year or more, develops crystals of concentrated flavor that crunch pleasantly between your teeth and leave a tangy afterglow.

Color presents another consideration. White cheddar and orange cheddar taste the same because that orange color comes from annatto, a natural dye that does nothing for flavor. The practice started when cheese makers wanted to signal that their cheddar came from cows eating fresh grass, which naturally tints milk slightly yellow. Now it’s just tradition, and you can pick whichever color pleases your eye without worrying about the taste.

3. Brie

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Kodai Cheese

Brie earns its reputation as the fancy cheese, though there’s nothing particularly difficult about eating it. This soft French cheese comes wrapped in an edible white rind that looks like velvet and tastes faintly of mushrooms. Inside, the paste ranges from firm and chalky when young to oozy and almost liquid when perfectly ripe.

The trick with brie involves catching it at the right moment. Too young, and it tastes like sour butter with no character. Too old, and it develops an ammonia smell that warns you it has crossed from ripe into spoiled. When you press the center and it gives slightly, like pushing on a ripe avocado, you’ve found the sweet spot where all those complex flavors come together.

Serve brie at room temperature, never cold, because refrigeration dulls its flavor and makes the texture unpleasantly firm. The rind is safe to eat, though some people scrape it off because they find the texture off-putting. Brie pairs beautifully with fruit, nuts, and crusty bread, making it the natural centerpiece of any cheese board that wants to look like you put some thought into it.

4. Parmesan (Parmigiano-Reggiano)

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Parmesan, or Parmigiano-Reggiano if you want to use its proper Italian name, stands as one of the world’s oldest cheeses. Italian law protects this name fiercely, allowing only cheese made in specific regions using traditional methods to call itself Parmigiano-Reggiano. Everything else is just parmesan, and the difference matters more than you might think.

This hard cheese ages for at least twelve months, though many wheels sit in temperature-controlled rooms for two or three years. During that time, enzymes break down proteins and fats into hundreds of flavor compounds that create that characteristic savory, slightly sweet, deeply complex taste. Those white crystals you find in good parmesan aren’t salt—they’re concentrated amino acids that crunch pleasantly and deliver intense bursts of flavor.

Buy parmesan in blocks and grate it yourself right before using it. Pre-grated parmesan loses its flavor within days and often contains cellulose powder to prevent clumping, which does nothing good for the taste. A little parmesan goes a long way because its flavor is so concentrated. Shave it over salads, grate it over pasta, or just eat chunks of it with good balsamic vinegar for a simple pleasure that requires no cooking whatsoever.

5. Gouda

Pin

Pin Courtesy Caws Teifi Cheese

Gouda comes from the Netherlands, where the Dutch have been making cheese since before they had a proper country. This semi-hard cheese has a mild, slightly sweet flavor when young that intensifies into something more complex and caramel-like as it ages. The texture stays smooth and sliceable, making gouda the reliable choice for sandwiches and cheese plates alike.

Young gouda, aged just a few weeks, has a supple texture and gentle taste that won’t offend anyone. Aged gouda, sometimes marked as “old” or “extra old,” develops those crunchy crystals and deep, butterscotch notes that make it interesting enough to eat on its own. Some varieties include added ingredients like cumin seeds or black pepper, though purists argue that good cheese needs no such embellishment.

The red or yellow wax coating on many goudas serves no purpose beyond marketing and must be removed before eating. Traditional gouda gets aged without wax, developing a natural rind instead. This cheese melts reasonably well and works in hot dishes, though it’s honestly better enjoyed cold or at room temperature where you can appreciate its buttery texture and subtle sweetness.

6. Blue Cheese

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Pixabay

Blue cheese divides people into two camps: those who love it and those who won’t go near it. The blue veins running through this cheese come from Penicillium roqueforti, a mold that cheese makers deliberately add to create those distinctive flavors. Before you get worried, remember that this is the same basic process that makes penicillin, and nobody complains about that.

The mold needs air to grow, so cheese makers pierce the wheels with long needles to create channels where oxygen can reach the interior. As the mold spreads, it breaks down fats and proteins into compounds that taste sharp, salty, and intensely savory. Different varieties of blue cheese—Roquefort, Gorgonzola, Stilton—use different molds and aging conditions to create their own personalities.

Blue cheese crumbles easily, making it perfect for salads where you want pockets of intense flavor scattered throughout milder greens. It also melts into cream sauces that coat pasta or vegetables with rich, funky goodness. If you find blue cheese too strong, start with a milder variety like Gorgonzola dolce, which balances the sharpness with creamy sweetness. The taste grows on you once you give it a fair chance.

7. Swiss (Emmental)

Pin

Pin Courtesy Christine Cast Iron Farm

Swiss cheese, properly called Emmental, gets its fame from those distinctive holes. Food scientists call them “eyes,” and they form when bacteria produce carbon dioxide during aging. The gas creates bubbles in the cheese, and those bubbles leave behind the round openings we all recognize. The size and distribution of the eyes indicate how well the cheese maker controlled the fermentation process.

The flavor of Swiss cheese leans mild and slightly nutty, with a firm but pliable texture that slices cleanly. It melts well without becoming greasy, making it the traditional choice for hot sandwiches and fondues. Baby Swiss, a smaller version with tinier holes and a softer texture, offers a gentler introduction for people who find regular Swiss too assertive.

Not all Swiss-style cheeses have eyes. Blind Swiss, made by controlling the bacteria more strictly, has no holes at all. Some manufacturers actually inject carbon dioxide to create artificial eyes in cheese that didn’t develop them naturally, which seems like cheating but technically works. For sandwiches and cooking, the holes don’t matter much. For impressing your friends with cheese knowledge, now you know why they’re there.

8. Feta

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Odyssey Brands

Feta comes from Greece, where shepherds have been making it for thousands of years. Traditional feta uses sheep’s milk or a mixture of sheep and goat milk, never cow’s milk, though many commercial versions break this rule. The cheese gets brined in salt water, which gives it that characteristic tangy, salty flavor and crumbly texture that falls apart when you try to slice it.

The tanginess in feta comes from the combination of lactic acid bacteria and the salt brine. Good feta tastes clean and bright, with a pleasant sourness that wakes up salads and cooked dishes. Bad feta tastes like salted chalk. The difference comes down to milk quality and how carefully the cheese maker controlled the process.

Feta belongs in Greek salads, obviously, but it also crumbles nicely over roasted vegetables, melts into omelets, and adds zip to pasta dishes. Store feta in its brine to keep it from drying out, and if the saltiness bothers you, rinse it under cold water before using. Some people soak particularly salty feta in milk for an hour to draw out excess salt, though this also softens the flavor along with the saltiness.

9. Provolone

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Facciola Winebar

Provolone descends from the same Italian tradition as mozzarella, using that pasta filata stretching method to create its smooth, firm texture. What separates provolone from its milder cousin is aging time and the addition of different bacterial cultures. Young provolone tastes mild and slightly sweet, while aged provolone develops a sharper, more assertive personality that demands attention.

This cheese comes shaped into various forms—balls, cones, cylinders—and often hangs from strings in Italian delis where it ages for anywhere from a few weeks to several months. The longer aging period allows enzymes to break down proteins and fats into more complex flavor compounds. Provolone piccante, the aged sharp variety, has a bite that stands up to strong Italian cured meats and vinegar-based dressings.

Provolone melts beautifully, making it excellent for sandwiches, especially when you want something more interesting than mozzarella but less aggressive than aged cheddar. It also works well in cooking, though the aged varieties have too much flavor to serve as a neutral melting cheese. For the best results, buy provolone from a deli counter where you can taste different ages and find the one that suits your preference.

10. Camembert

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Pizza 4P’s India

Camembert closely resembles brie, and many people can’t tell them apart at a glance. Both come from France, both have white rinds, and both get soft and runny as they ripen. The main difference lies in size—camembert comes in smaller wheels—and flavor intensity. Camembert tastes earthier and more mushroom-like than brie, with a stronger aroma that some people find off-putting until they try it.

Like brie, camembert ripens from the outside in. The white mold on the surface produces enzymes that slowly break down the cheese, turning the firm paste near the rind into a creamy, almost liquid layer. A perfectly ripe camembert has a firm center surrounded by that oozy layer. Cut into it too early and you get bland, chalky cheese. Wait too long and you get ammonia fumes that warn everyone in the room that you missed your window.

Serve camembert at room temperature, or bake it whole in its wooden box for a warm, gooey appetizer that you scoop up with bread. The rind is edible and contributes to the overall flavor profile, though some people find its texture unpleasant. Camembert pairs well with apples, pears, and wine, making it a reliable choice when you want to feel like you’re having a sophisticated snack.

11. Gruyère

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Fromage Gruyere SA

Gruyère comes from Switzerland, where it has been made since the 12th century in the town that gave it its name. This hard cheese ages for at least five months, developing a complex flavor that balances sweet, salty, and nutty notes. The texture stays firm and sliceable, though it melts into a smooth, creamy consistency that makes it the cheese of choice for fondue and French onion soup.

What sets Gruyère apart from similar cheeses is its depth of flavor. Young Gruyère tastes mild and creamy with subtle nuttiness. As it ages, it develops more pronounced fruity and earthy notes, along with those characteristic crunchy crystals that indicate proper aging. The holes in Gruyère are much smaller than Swiss cheese holes, barely noticeable unless you look closely.

Gruyère costs more than everyday cheeses, but the price reflects the careful production methods and long aging time. You can substitute it with Swiss or Emmental in most recipes, though you’ll lose some complexity. For gratins, quiches, and any dish where the cheese plays a starring role, Gruyère delivers flavors that cheaper alternatives can’t match. Grate it, melt it, or slice it for sandwiches—all three applications showcase what makes this cheese worth seeking out.

12. Monterey Jack

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Ullrich’s Pembroke

Monterey Jack was invented in California during the 1800s, making it one of the few genuinely American cheeses. This semi-hard cheese has a mild, buttery flavor and a high moisture content that makes it melt smoothly. Young Monterey Jack tastes gentle enough for children and picky eaters, while aged versions called Dry Jack develop harder textures and sharper flavors that can compete with aged cheddar.

The cheese got its name from David Jacks, a businessman who marketed it widely, though he probably didn’t invent it himself. Traditional Monterey Jack has no added ingredients, but pepper jack includes jalapeño peppers and sometimes other spices that give it a spicy kick. Colby Jack combines Monterey Jack with Colby cheese in a marbled pattern that looks nice but doesn’t change the flavor much.

Monterey Jack melts beautifully without separating or getting greasy, making it perfect for quesadillas, nachos, and any Tex-Mex dish that needs cheese. The mild flavor won’t overpower other ingredients, which makes it useful in recipes where you want cheese texture without strong cheese flavor. Keep Monterey Jack in your refrigerator as your reliable melting cheese when mozzarella seems too Italian and cheddar seems too British for what you’re cooking.

13. Manchego

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Spain

Manchego comes from Spain, specifically from La Mancha, the same region that inspired the adventures of Don Quixote. This sheep’s milk cheese has been made the same way for hundreds of years, following strict rules about what kinds of sheep, what grazing lands, and what aging conditions qualify as authentic Manchego. The result is a firm cheese with a distinctive herringbone pattern pressed into its rind.

The flavor of Manchego depends on aging time. Young Manchego, aged just two months, tastes mild and buttery with a slight tang from the sheep’s milk. Aged Manchego, left to mature for a year or more, develops nutty, caramel-like notes and a firmer, more granular texture. Sheep’s milk gives all Manchego a richer, more complex base flavor than cow’s milk cheese, with a slight barnyard quality that some people love and others find too strong.

Manchego belongs on cheese boards alongside Spanish ingredients like olives, almonds, and quince paste. It also melts reasonably well, though its best qualities shine when you eat it at room temperature where the full range of flavors comes through. Slice it thin for sandwiches or cube it for snacking. Either way, you’re getting a taste of Spanish tradition that has survived because it simply tastes good.

14. Havarti

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Buholzer Brothers

Havarti hails from Denmark, where a farm woman named Hanne Nielsen developed it in the mid-1800s after studying cheese-making techniques across Europe. This semi-soft cheese has a buttery, slightly tangy flavor and a supple texture full of small irregular holes. The taste stays mild enough for everyday eating but interesting enough that you won’t get bored of it.

What makes Havarti useful is its versatility. It melts smoothly for hot sandwiches and burgers. It slices cleanly for cold sandwiches and cheese plates. It even crumbles reasonably well over salads when you need something softer than feta but more flavorful than mozzarella. Flavored varieties include dill, caraway, jalapeño, and garlic, though the plain version has enough character to stand on its own.

Havarti ages quickly, developing a sharper flavor within just a few months. Most of what you find in stores is young Havarti, mild and creamy. If you spot aged Havarti at a cheese counter, grab some to see what this cheese becomes when given more time. The interior develops a deeper yellow color and the flavor intensifies into something that resembles a mild cheddar with more complexity and creaminess.

15. Ricotta

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Ricotta Cheese

Ricotta isn’t technically cheese in the traditional sense. Most cheese comes from curdling milk directly, but ricotta gets made from the whey left over after making other cheeses. Italian cheese makers, too practical to waste anything, discovered that heating whey causes the remaining proteins to form soft, grainy curds. The name means “recooked” in Italian, referring to this second heating process.

Fresh ricotta has a mild, slightly sweet flavor and a texture like fine-grained cottage cheese. It’s wet enough to spread but not so wet that it runs off your spoon. The best ricotta tastes clean and milky, with just a hint of sweetness. Commercial ricotta often includes stabilizers and gums to extend shelf life, which changes the texture into something more uniform but less interesting.

Ricotta belongs in lasagna, stuffed shells, and cannoli filling, where its mild flavor and creamy texture complement stronger ingredients without competing. You can also eat it on toast with honey, mix it into pancake batter for extra moisture, or use it as a base for dips. Fresh ricotta spoils quickly, so use it within a few days of opening. The watery liquid that accumulates on top is whey—you can drain it off or stir it back in depending on whether you want thicker or looser ricotta.

16. Asiago

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Caform Japan

Asiago comes from northeastern Italy, where it exists in two distinct forms. Fresh Asiago, aged just a few weeks, has a soft, smooth texture and mild flavor similar to a firmer version of mozzarella. Aged Asiago, matured for nine months or longer, becomes hard and granular like Parmesan, developing sharp, nutty flavors that make it suitable for grating over pasta.

The difference between fresh and aged Asiago is so dramatic that you might not recognize them as the same cheese. Fresh Asiago melts nicely and works well in sandwiches or on burgers where you want something more interesting than provolone but less aggressive than aged cheddar. Aged Asiago doesn’t melt as smoothly, but its concentrated flavor means you need less of it to make an impact.

Most grocery stores carry aged Asiago rather than fresh, which makes sense because aged cheese ships better and lasts longer. If you find fresh Asiago at an Italian deli or specialty shop, buy some to understand the full range this cheese covers. You can substitute aged Asiago for Parmesan in most recipes, though it has a slightly different flavor profile that leans more toward sharp and tangy than sweet and nutty.

17. Cream Cheese

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Essence Cheese

Cream cheese emerged in America during the late 1800s when a New York dairyman developed a method for making richer, smoother cheese by adding cream to milk. The result had a mild, slightly tangy flavor and a spreadable texture that made it perfect for bagels. Philadelphia became the dominant brand name, so much so that many people call all cream cheese “Philadelphia” regardless of who made it.

The fat content in cream cheese ranges from full-fat versions with 33% milk fat down to reduced-fat and fat-free versions that use gums and stabilizers to mimic the texture. Full-fat cream cheese spreads smoothly, blends easily into cheesecake batter, and tastes rich without being overwhelming. Lower-fat versions work fine for spreading but don’t perform as well in baking or cooking where fat content affects texture and moisture.

Cream cheese softens at room temperature, making it easier to spread or blend. If you forget to take it out of the refrigerator ahead of time, cut it into chunks and microwave it briefly, checking every ten seconds to avoid melting it. Whipped cream cheese spreads more easily straight from the refrigerator because air has been beaten into it, though it doesn’t work well in recipes that specify regular cream cheese because the volume measurements don’t match.

18. Colby

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Shop Victual

Colby cheese was invented in Wisconsin in 1885, named after the town where it originated. This mild, semi-hard cheese resembles cheddar in appearance but has a softer, more open texture with higher moisture content. The curds get washed with cold water during production, which removes some of the lactic acid and creates a milder, sweeter flavor than cheddar.

The texture of Colby feels springier and less dense than cheddar. It doesn’t age well—most Colby gets eaten young, within a few months of production. Trying to age Colby just makes it dry and crumbly without developing the complex flavors that make aged cheddar interesting. This cheese works best as an everyday eating cheese for people who find cheddar too sharp and Monterey Jack too bland.

Colby melts reasonably well, though not as smoothly as Monterey Jack. You’ll often find it mixed with Monterey Jack in a marbled pattern sold as Colby Jack, which combines the mild sweetness of Colby with the better melting properties of Jack. Use Colby in sandwiches, on crackers, or cubed for snacking. Don’t bother cooking with it unless you need a mild melting cheese and happen to have Colby on hand.

19. Fontina

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Appetite London

Fontina originates from the Valle d’Aosta in northwestern Italy, where cows graze on mountain pastures that give the milk distinctive flavors. Real Fontina Val d’Aosta has a protected designation, meaning only cheese made in that specific region following traditional methods can use the full name. What you find in most grocery stores is Fontina-style cheese made elsewhere, which tastes similar but lacks some of the complexity.

This semi-soft cheese has a pale yellow interior with small holes scattered throughout. The flavor balances mild nuttiness with a slight earthy quality and a hint of mushroom. Fontina melts beautifully, becoming creamy and smooth without separating or getting greasy. Italian cooks use it in fonduta, a fondue-like dish, and over polenta where its melting properties and rich flavor shine.

Young Fontina has a supple, sliceable texture good for sandwiches and cheese plates. As it ages, the texture firms up slightly and the flavor intensifies, though most Fontina gets eaten young. Store Fontina wrapped in wax paper or cheese paper rather than plastic wrap, which traps moisture and encourages unwanted mold growth. Let it come to room temperature before serving to appreciate the full range of flavors that cold temperatures suppress.

20. Cotija

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Cotija cheese

Cotija comes from Mexico, named after the town of Cotija in Michoacán. This hard, crumbly cheese resembles feta in texture but has a saltier, more intensely savory flavor. Traditional Cotija ages for several months, developing a firm texture that crumbles easily and doesn’t melt. Mexican cooks use it as a finishing cheese, crumbling it over tacos, elotes (grilled corn), beans, and salads.

Two types of Cotija exist: fresh and aged. Fresh Cotija, also called Cotija fresco, has a softer texture and milder flavor similar to feta. Aged Cotija, sometimes called añejo, becomes hard and salty with a concentrated flavor that stands up to spicy dishes. The aged version is what most people mean when they say Cotija, and it’s the one you’re more likely to find in stores.

Cotija doesn’t melt, which confuses people expecting it to behave like other cheeses. Instead, it softens slightly and holds its shape, making it perfect for topping hot dishes where you want cheese flavor without cheese goo. The high salt content acts as a preservative, so Cotija lasts longer than soft cheeses. If you can’t find Cotija, aged feta makes a reasonable substitute, though it has a tangier flavor and slightly different texture.

21. Pecorino Romano

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Global Horeca

Pecorino Romano comes from central Italy, made from sheep’s milk following methods that date back to Roman times. The name tells you everything: pecorino means sheep’s cheese in Italian, and Romano indicates its connection to Rome. This hard, salty cheese has a sharp, assertive flavor that dominates any dish you add it to, which is exactly what traditional Italian cooking calls for in certain preparations.

The production process involves salting the cheese wheels heavily and aging them for at least five months, though many wheels age for eight to twelve months. This creates a rock-hard texture that requires a sharp grater and a firm grip. The flavor is intensely salty and tangy, much more aggressive than Parmesan. A little Pecorino Romano goes a long way—you need about half as much as you would Parmesan to achieve the same flavor impact.

Pecorino Romano belongs in classic Roman pasta dishes like cacio e pepe, carbonara, and amatriciana, where its sharp saltiness balances rich ingredients like guanciale and pasta cooking water. You can substitute it for Parmesan in most recipes, but adjust the amount and be prepared for a different flavor profile. Some people mix Pecorino and Parmesan half and half to get the best qualities of both cheeses without either one overwhelming the dish.

22. Boursin

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Liza

Boursin represents a modern approach to cheese-making, invented in France in 1957 by François Boursin. This soft, spreadable cheese comes flavored with herbs, garlic, and spices mixed directly into the cheese rather than added as a coating. The texture resembles cream cheese but fluffier and lighter, with a tangy base flavor that comes from the addition of crème fraîche.

The most popular variety combines garlic and fine herbs, creating a savory spread that works on crackers, bread, or vegetables without any additional preparation. Other flavors include pepper, shallot and chive, and cranberry. All varieties share that same soft, spreadable consistency that makes them useful for quick appetizers when you don’t have time to assemble a proper cheese board.

Boursin melts into a creamy sauce when heated, making it useful for quick pasta dishes or as a topping for baked chicken or fish. The flavors are already built in, so you don’t need to add much else beyond the cheese itself. Store Boursin in its original packaging and use it within a few days of opening, as the high moisture content means it doesn’t keep as long as harder cheeses. If the price seems high for such a small package, remember that a little Boursin delivers more flavor than a larger amount of plain cream cheese.

23. Limburger

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Selfsustainable Me

Limburger earned its reputation as the smelliest cheese in the world, though that reputation is somewhat exaggerated. This soft cheese originated in Belgium but became popular in Germany and eventually found a devoted following in parts of the United States where German immigrants settled. The smell comes from Brevibacterium linens, the same bacteria that causes foot odor, which cheese makers deliberately spread on the surface.

The aroma is genuinely strong—there’s no point pretending otherwise. Opening a package of Limburger will announce itself to everyone in the room. But here’s the curious thing: the taste is much milder than the smell suggests. The interior has a smooth, almost sweet flavor with just a hint of that pungent quality. People who work up the courage to try it often find themselves surprised by how edible it is.

Limburger softens as it ages, starting firm and becoming increasingly creamy. Eat it on dark rye bread with onions and mustard, the traditional German way, which helps balance the strong flavors. If you want to try Limburger but fear the smell will overwhelm you, start with a young piece and work your way up to aged versions. The cheese has survived for centuries because enough people genuinely enjoy it, even if they have to open the windows while doing so.

24. Halloumi

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Shruti

Halloumi comes from Cyprus, where it has been made for centuries from a mixture of sheep and goat milk. What makes this cheese remarkable is its high melting point. While most cheeses turn liquid when heated, halloumi holds its shape, developing a golden-brown crust on the outside while staying soft and chewy inside. This unique property comes from the cheese-making process, which involves cooking the curds at high temperatures.

The flavor of halloumi is mild and slightly salty, with a texture that squeaks against your teeth when you bite into it. That squeak indicates fresh halloumi—as the cheese ages, it loses that characteristic. Raw halloumi tastes fine but not particularly interesting. Grilled or fried halloumi transforms into something special, with a crispy exterior giving way to a warm, elastic interior that has a texture unlike any other cheese.

Cook halloumi in a hot, dry pan or on a grill, flipping once to brown both sides. It takes just a few minutes and needs no oil because the cheese contains enough fat to prevent sticking. Serve it as a vegetarian main course, add it to salads for protein and texture, or eat it as an appetizer with lemon juice squeezed over the top. Halloumi comes packed in brine, which you should drain off before cooking. If it tastes too salty, soak it in water for an hour to draw out excess salt.

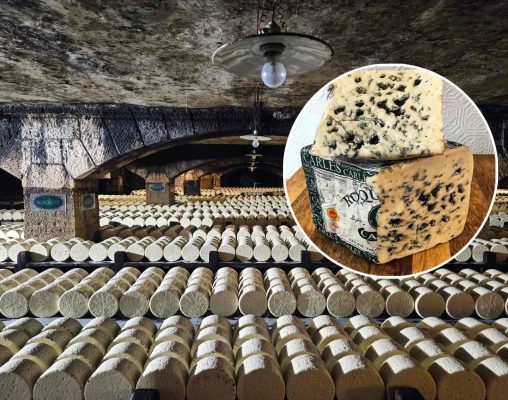

25. Roquefort

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Coleni9

Roquefort stands as one of the oldest known cheeses, with records mentioning it as far back as the year 79. This French blue cheese comes from sheep’s milk and ages in natural caves in the Roquefort-sur-Soulzon region, where specific molds in the air contribute to its distinctive character. French law protects the name Roquefort as strictly as it protects Champagne—only cheese aged in those specific caves can use the name.

The flavor is intensely sharp and salty, with a crumbly, moist texture that falls apart easily. Roquefort tastes stronger than most other blue cheeses because sheep’s milk provides a richer base and the aging process in those caves develops more complex mold flavors. The blue-green veins run throughout the cheese in irregular patterns, and the paste itself ranges from white to pale yellow.

Roquefort belongs crumbled over salads, mixed into compound butter, or eaten with sweet accompaniments like honey, figs, or pears that balance its aggressive saltiness. A small amount delivers substantial flavor, so buy just what you’ll use in a week or two. The cheese should look moist but not wet, crumbly but not dry. If you find Roquefort too strong, try mixing it with cream cheese or butter to mellow the flavor while maintaining that characteristic blue cheese taste.

FAQs

Hard cheeses like cheddar and Parmesan freeze reasonably well, though the texture becomes crumblier after thawing. Soft cheeses turn grainy and watery when frozen, so it’s better to use them fresh or buy smaller amounts.

Cheese needs to breathe, so plastic wrap traps moisture and encourages mold. Wrap cheese in wax paper or cheese paper, then loosely in plastic, and store it in the warmest part of your refrigerator, usually the vegetable drawer.

Natural cheese contains just milk, cultures, enzymes, and salt. Processed cheese includes emulsifiers, preservatives, and other additives that give it a longer shelf life and smoother melting properties but less complex flavor.