Electricity is a powerful force in nature, and some animals wield it like superheroes in a comic book. These creatures use electricity to hunt, defend themselves, or navigate their murky habitats. Here’s a closer look at the top animals that can give you a literal shock and their electrifying abilities.

Pin

Pin Table of Contents

Electric Eel (Electrophorus electricus)

Pin

Pin Despite its name, the electric eel is not a true eel but a member of the knife fish family. Found primarily in the Amazon and Orinoco River basins in South America, an electric eel can generate up to 600 volts of electricity—enough to stun a horse! This shocking ability is used to locate prey, communicate, and, of course, defend itself.

Taxonomically, it belongs to the order Gymnotiformes, which includes several species of electric fish. More specifically, it is a part of the knife fish family, which are known for their elongated bodies and the capability to generate electric fields.

The electric eel’s most renowned feature is its ability to produce substantial electrical charges, which can reach up to 600 volts. This is an extraordinary feat of biological engineering. The eel uses this electrical power not only as a predator deterrent but also as a sophisticated sensory and communication apparatus. To understand how they generate this electricity, it’s essential to look into their unique physiology.

An electric eel’s body contains specialized cells called electrocytes. These cells function much like batteries, arranged in series and stacked along the animal’s body. When the eel decides to discharge, these cells can create a sudden burst of electricity. A full-grown electric eel has enough electrocytes to stack up to a six-foot-long battery. The electric organ takes up about four-fifths of its body, leaving only a small portion for all its other organs.

These electrical discharges serve several purposes. Predominantly, electric eels use this ability to stun or outright incapacitate prey such as fish, amphibians, and even small mammals. The shock can be so powerful that it does, indeed, have the capacity to stun a fully grown horse. Furthermore, the electric eel uses electric fields for navigation and locating objects in the murky waters where it dwells, a process known as electrolocation.

During electrolocation, the electric eel emits a low-voltage charge that interacts with objects and living creatures in the surrounding environment. Changes in the electric field return to the eel, providing it with information on the location, size, and movement of nearby objects or organisms.

This capability is particularly beneficial in the electric eel’s habitat, where visibility is often poor.

Additionally, electric eels use their electrical abilities to communicate with one another, especially during mating season. The pattern and intensity of electric discharges are distinct, probably allowing individual eels to identify and respond to potential mates, rivals, or threats.

Understanding electric eels is not only of interest to naturalists. The study of their unique electric organs is of significant interest to scientists, especially in fields such as bioelectronics. Research into how electric eels generate and control electricity could lead to advances in medical devices, power generation, and artificial electric receptors.

The electric eel—with its misnomer—is a distinct species that combines the ancient, murky waters of its habitat with a touch of modernity through the remarkable use of bioelectricity. It is an animal that poses a significant interest to both the curious onlooker and the dedicated researcher, as it continues to shock the world in more ways than one.

Electric Ray (Torpedo family)

Pin

Pin Beware the sandy seabeds where electric rays may be hiding. These flat fish, known for their rounded bodies and eyes on top of their heads, can produce an electric discharge ranging from 8 to 220 volts. The shocks help the rays to debilitate prey such as fish and crustaceans.

In the quiet drama that unfolds beneath the ocean’s surface, the sandy seabeds host a deceptive hunter—the electric ray. Members of the Torpedo family, these creatures are the enigmatic sorcerers of the deep. With bodies shaped like rounded discuses, they are a sight to behold, blending the line between fish and phantoms. Noted for their peculiar top-mounted eyes, these eyes peer like periscopes, scanning for movement above while the rest of their form nestles within the ocean floor’s embrace.

The electric ray’s true prowess, however, lies hidden within its innocuous appearance. Beneath its skin are specialized organs known as electric organs, which are constructed from modified muscle or nerve cells called electrocytes. These cells act like batteries, lined up in series and capable of generating electric discharges that vary greatly in intensity—from a mere tingle of 8 volts to a formidable jolt of 220 volts.

A small fish, darting carelessly above the seabed. It does not notice the barely visible outline of the electric ray hidden below. In a flash, the ray releases its built-in weaponry, sending a surge of electrical force through the water. It’s a spectacle not seen but felt. The prey, struck by the sudden charge, finds itself enveloped in an unseen grip, muscles convulsing, temporarily paralyzed. The electric ray emerges from its sandy lair like a specter, slowly approaching the immobilized fish, which is to become its next meal.

The discharge also serves as a formidable defense mechanism. Any potential predator contemplating a taste of the ray would retreat, reconsidering its choices when faced with the tingling warning of the ray’s electrical might. Such encounters remain rare, for the creatures of the deep have learned to give wide berth to the soft, sandy patches that might conceal this electric hunter.

But the electric ray does more than hunt and defend. It is a creature of mystery and wonder, a living reminder of nature’s inventiveness. Mariners of old spun tales of these ‘numbing fish’ that could sate the wrath of the sea with a mere touch. Scientists marvel at their unique bioelectrogenesis ability, continuing to study it in hopes of unlocking new understanding in bioelectricity and neurology.

In depths where sunlight falters, on the seabed’s shifting canvas, the electric ray plays out its role in the great tapestry of ocean life—unseen, powerful, and electric in every sense of the word. It is a creature worthy of both respect and distance, for within its unassuming form lies the power to illuminate the mysteries of the deep and remind us of the beauty and danger artfully mingled in nature’s design.

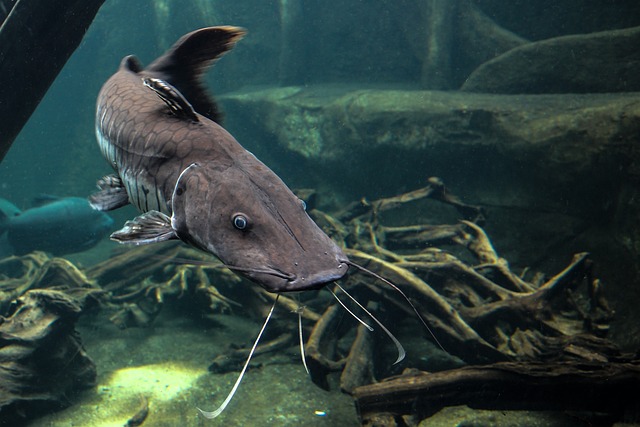

Electric Catfish (Malapteruridae family)

Pin

Pin Mostly found in tropical Africa, electric catfish can produce up to 350 volts of electricity. They use their power for defense and predation. Interestingly, historical accounts suggest that ancient Egyptians may have used these fish for medical shock therapy.

In the lush, rippling waters of tropical Africa, a creature swims silently, enshrouded in mystery and ancient tales – the electric catfish, scientific name Malapterurus electricus, belonging to the family Malapteruridae. Though it may appear as an ordinary catfish with its barbels and elongated body, it conceals within its flesh the startling ability to unleash a formidable electrical charge, an evolutionary marvel perfected over millennia.

This fish, which can grow to a notable size, navigates the muddy riverbeds, wielding an electrical force that can surge up to a staggering 350 volts. This extraordinary power serves a dual purpose: defense and predation. When threatened, the electric catfish generates a pulsating electric field, a natural weapon intimidating potential foes. Predation becomes an effortless task as the fish uses its bioelectricity to stun unwary prey, such as smaller fish, which it can then engulf without a struggle.

But the electric catfish is not just a predator; it is a bearer of stories that stretch back to antiquity. Carved into the stone of Egyptian temples and mentioned in papyrus texts, there are intriguing narratives that these creatures were more than mere inhabitants of the Nile. Ancient Egyptians, ever-advanced in their medical knowledge, may have found a medicinal purpose for the catfish’s shocking abilities. Intriguing historical accounts lead us to believe that they employed the electric shocks in therapeutic practices, possibly to relieve pain or to treat various ailments by stimulating muscles or nerves, an early form of electrotherapy.

Ancient Currents: The Elemental Healer and the Electricity of Life (This is a Fictional Scene or Imagination, Do Not Try)

A world far removed from our modern understanding of medicine, an ancient healer orchestrates a treatment, a mixture of mysticism and empirical knowledge. The patient, awaiting relief from their suffering, watches as the healer gently coaxes the fish from its aquatic home. With careful intent, the healer uses the electricity from the fish in a rudimentary form of shock therapy, perhaps eliciting awe and wonder from the onlookers.

This practice, shadowy as it is across the span of time, speaks to the resourcefulness and innovation of ancient civilizations. It underlines how the nature surrounding them was not only a source of wonder but also of well-being, integrating the electric catfish into their very cultural and medicinal tapestry.

Today, the electric catfish still thrives in the freshwaters of Africa, largely unchanged, an enduring testament to the power and complexity of evolution. It continues to capture the imagination, now of scientists and curious minds, who study its abilities in hopes of uncovering more of its secrets. In the silent, swirling waters it calls home, the electric catfish swims on – a living conduit between the ancient and the modern, the understood and the mystical.

Electric Stargazer (Astroscopus family)

Pin

Pin With eyes perched on top of its head and a mouth facing upwards, the stargazer buries itself and delivers shocks to unsuspecting prey that swim by. Their voltage can reach up to 50 volts, mainly serving as a weapon to capture meals.

In the dimly lit underwater realms, where the seabed becomes a stage for survival, the electric stargazer from the Astroscopus family engages in an unassuming hunt. This singular creature, more an artist of ambush than a relentless predator, adapts a form finely tuned for its environment. Its body merges seamlessly with the sandy or muddy bottom, resembling a rocky outcrop or a patch of sea floor.

The stargazer, unassuming in repose, is equipped with a natural arsenal that defies the passive nature of its appearance. With eyes that rise like periscopes atop its head, it surveils the world above, a silent sentinel in its sandy fortress. Its upward-facing mouth is not merely an anatomical curiosity but an integral aspect of its predatory tactic.

As the stargazer lies in wait, buried but for its eyes and mouth, it merges so wholly with its environs that unsuspecting prey would only recognize their peril when it was far too late. Fish, accustomed to the open and seemingly innocuous spaces above the seabed, swim by, oblivious to the lurking danger beneath.

Then, in a flash of action that disturbs the otherwise still waters, the stargazer reveals its formidable weapon: an organ capable of producing electrical shocks up to 50 volts. This jolt is no mere parlor trick; it is the stargazer’s means of survival, its method of ensnaring the unwary. The current it releases serves a dual purpose—not only does it stun and disorient its prey, but it also compels the unlucky victim towards its gaping maw.

The startled prey, now in the throes of the electric grasp, is consumed with ruthless efficiency. To the world above, the disturbance is a mere flutter, a ripple on the surface, but for the prey, it is the end — a sudden and shocking finale.

Observers of the stargazer might contemplate the silent, electric drama with a sense of wonder and a touch of dread. Here, in the deep, lies a creature whose very existence challenges our notions of power and predation. It is a living testament to nature’s complexity, where electricity is not the domain of the skies above but an elemental force wielded beneath the waves by a creature as enigmatic as the night sky itself.

Narwhal (Monodon monoceros)

Pin

Pin While not electric in the traditional sense, the narwhal has made this list thanks to recent studies that suggest these “unicorns of the sea” might use their iconic tusks to detect changes in water temperature, salinity, and even electrical fields hinting at the presence of prey and predators.

In the frigid embrace of the Arctic waters, there exists a creature as enigmatic as it is endearing. The Narwhal, or Monodon monoceros, possesses an attribute that seems extracted straight from the realm of myth — a spiraled tusk that has captivated the human imagination for centuries. This singular “horn,” an elongated tooth with helical grooves, has likened these creatures to the fabled unicorns, earning them the title “unicorns of the sea.”

But the narwhal’s tusk is far more than a mere appendage of fantasy. Beyond its surreal appearance, modern research reveals a surprising possibility; it may serve as a unique sensory organ. Recent studies have nudged science closer to unraveling this mystery, suggesting that the narwhal’s tusk may be sensitive to various environmental factors, including temperature gradients, water column salinity, and perhaps most fascinatingly, electrical fields that pervade the ocean’s depths.

The Narwhal’s Tusk as Nature’s Compass

A silent, shadowy world under a ceiling of ice. Here, the narwhal navigates the darkness, not just with sight and sound, but possibly with the subtle guidance of its own biological compass, its tusk acting as a conduit of sensory information. In the murky waters, where every advantage counts, this capacity might inform the narwhal of approaching predators, stealthily gliding through the water, or it might signal the presence of prey — a flicker of electricity amid the stillness that harks to life and sustenance.

The hows and whys of this possible sensory perception lie within the tusk’s unique structure, lined with millions of nerve endings that connect to the narwhal’s central nervous system. Such biological wiring could theoretically render the tusk a sensitive probe, picking up the faintest whispers of movement through the conductivity of the saline water that cradles the Arctic giants.

Upon the discovery, we envision the narwhal, gliding through the saltwater currents as though it were tracing the threads of a watery web. Amidst the cold, where every sense is heightened, the tusk leads the way, revealing a tapestry of signals — warm currents that weave around ice floes, saline signatures of tidal fluctuations, and the electric dances of small fish darting through the inky sea.

The narwhal exemplifies nature’s knack for artistry — a blend of form and function, poetry and pragmatism. Much remains unknown, veiled in the depths of the ocean and the nascent stages of scientific inquiry, but this novel perspective shines a light on the narwhal’s tusk in remarkable new ways, transforming it from an instrument of folklore into a potential key unlocking hidden ecological interactions at the heart of one of Earth’s most extreme environments.

As we continue to piece together this intricate puzzle, the narwhal floats on, a living testament to the Earth’s capacity for wonder, ever guiding us to broaden the boundaries of our understanding of the natural world and the myriad ways life adapts to its surroundings.

Echidna (Tachyglossus aculeatus)

Pin

Pin In the veil of the Australian underbrush, where the untamed foliage whispers ancient tales, the quaint echidna roves with quiet assurance. These solitary beings, echoes of prehistoric times with their spiny armor and roving snouts, carry within them a secret that bridges the realms of animal ingenuity.

The echidna, an enigma swathed in a coat of spikes, is a rarity amongst the mammalian ilk – an egg-layer, a custodian of a lineage stretching back to the time when reptiles transitioned to birds and mammals. Unique to its kind, it is known for an ability that seems almost mystical, if not for the grounded science behind it: the power to detect the faint whispers of life beneath the earth, the electrical impulses invisible to the eye and silent to the ear.

With a snout that serves as both a sword and wand, the echidna gently probes the humus-rich soil, its electroreceptors finely tuned to the symphony of the underground. As it forages, immersed in its search, the echidna’s world narrows to the delicate pings of electrical signals. Tiny dramas unfold in the dark loam – a worm shuffles through the decomposing leaves, a beetle larva wriggles in its earthen cocoon, their biological rhythms casting faint electrical auras in their wake.

Unseen to most, these pulses are like the beat of a drum to the echidna’s perceptive receptors, drawing it ever closer. With patient precision, it excavates the source of this living rhythm, the long, slender tongue flickering with an eager anticipation that belies its otherwise stoic demeanor.

In the echidna’s search, there is a silent grace, a communion with the invisible forces that thread through all living forms. It is a reminder of the interconnected nature of life, where even the faintest current is a beacon in the patina of the natural world.

Electroreception, the echidna’s gift, is more than a mere tool for survival; it is a testament to the rich tapestry of evolution, a subtle adaptation that has allowed it to thrive in an ever-changing world. In its quiet quest for sustenance, the echidna not only reveals the hidden narratives playing beneath our feet but also humbles us with the reminder of nature’s endless creativity.

Elephant Nose Fish (Gnathonemus petersii)

Pin

Pin In the murky waters of the African riverine systems dwells a creature as enigmatic as it is peculiar—the elephant-nose fish. Despite what its name might imply, this creature bears no true kinship with the great terrestrial behemoths. Its defining feature, an elongated appendage jutting forth from its lower jaw, is no prehensile trunk but an adaptation of an altogether different sort. This long chin, resembling an aerial that’s been misplaced on the anatomy of a fish, is an exquisite tool, a sensor of the silent electrical whispers of life in the aquatic murk.

The elephant-nose fish has perfected the art of electroreception. Its fleshy, pendulous chin is dotted with cells capable of detecting the faintest electrical fields emitted by all living organisms. As it glides through the pitch-dark waters of its habitat, where not even the faintest rays of sunlight can penetrate, it navigates a world invisible to the eyes. Where other creatures would find themselves blind and disoriented, the elephant-nose fish thrives.

Each sweep of its peculiar “nose” sends out a signal, an electrical pulse so subtle it yields no disturbance in the water, yet it maps the world around it in precise detail. The returning echoes paint a picture in the fish’s mind of prey burrowed away in silt, of the contours of the riverbed, and of the presence of fellow fish perhaps veiled by night or the churn of sediment-heavy currents. This biological sonar allows the elephant-nose fish to not only survive in the opaque environment but to become a deft hunter. A creature that can perceive life itself through the veil of eternal darkness.

With this extraordinary ability to detect, analyze, and react to environmental electric impulses, the elephant-nose fish spends its existence in a delicate dance with the invisible forces that surround it. It is a living testament to the intricacies of evolution, a solitary figure that probes the enigmatic electric networks of life in the water. The fish, often solitary, leads a life that is as complex as the environment it navigates, though its interactions with the world around it are as silent as the depths in which it dwells.

In a world where vision falls short, the elephant-nose fish has blossomed into a creature tailored to its unique niche. Its distinctive “nose” pulses with the unseen rhythms of the river, a ballet of life conducted beneath the surface of the water—an elegant synchronization with the silent and invisible world that it alone can sense and interpret. The waters whisper their secrets, and the elephant-nose fish, humble and extraordinary, listens intently to the electrical heartbeats of its underwater realm.

Bees (Apis mellifera)

Pin

Pin Within the vibrant tapestry of a garden, where the air is heavy with the scent of blooming life, a subtle dance of energy and allure takes place between flowers and their winged suitors, the bees. This is not merely a visual affair; beyond the riot of color and the intoxicating fragrance lies an invisible layer to this delicate interaction—an electrical one.

Each flower, resplendent in its bright petals, is more than a beacon of color. It’s a bastion of electric charge. Unseen to the human eye, every bloom is charged with a halo of electric potential, created by the floral dance of positive and negative ions. This electric signature is as integral to the plants as their pigments and scents. It whispers promises of nectar and pollen to those that can hear its silent hum.

Bees, the deft foragers that they are, have evolved to sense the world in a way humans can scarcely imagine—they perceive the electric. Tiny hairs on the bees’ bodies vibrate in response to electrostatic fields, giving these industrious insects a sense of electric landscapes overlaid upon the colorful ones we see. With this ability, they glide from flower to flower, not solely seduced by the brightness of petals or their seductive perfume.

For bees, the electric charge of a flower is a storybook, one of recent history and presence. Once a bee lands and delves into the chamber of petals to feast on nectar and bathe in pollen, it leaves more than a trail of physical contact. The flower undergoes an electric change, its potential altering, the charge slightly diminished by the bee’s touch—a floral visitor’s indelible signature.

As the bee bumbles away, satiated, this change in electric charge lingers like a whispered secret, a sign that reads “visited” in a language only those with electric senses can decode. The next bee, buzzing its way through, sweeps near the flower and senses the drop in voltage, the shift in the electric story. It tells them unmistakably that another has come before, that the riches may be plundered, and they must decide: is it worth investigating, or should it move on, seeking an untouched bloom rich with potential?

Thus, the bees flit from flower to flower, guided by sight, scent, and the silent pull of electric cues, participating in an ancient and intricate electricity-laced ballet. It’s a dance of life and coexistence, a complex communication between species, where electric charges carry messages across the petals and inform choices that sustain both the foragers and the flora.

In this hidden electric theater, bees are the audience and the actors, attuned to the shifting scenes of charge that help ensure their survival and the continuation of the botanical world. It’s a reminder of the complex layers of interaction in nature, and the wonders that lie just beyond our perception, where even a thing as ephemeral as a static charge can shape the daily rhythm of the living Earth.

Oriental hornets (Vespa orientalis)

Pin

Pin In the annals of the natural world, where fact can eclipse fiction, there exists a creature seemingly sprung from the pages of a superhero comic. The Oriental hornet, a being cloaked in the vibrant hues of yellow and brown, veils within its striking form a marvel of biological engineering, a power that defies the mundane crawlings of its earthbound kin. For unlike any other member of the animal kingdom, this insect wields the astonishing capability to draw energy from the sun itself.

The saga of the Oriental hornet’s extraordinary ability begins with its unique exoskeleton. Picture the yellow parts of its body, not merely for ornamentation but as living solar panels. Within these yellow tissues lies a complex microscopic structure capable of trapping sunlight. But the marvel does not end there; the insect’s brown tissues enter the narrative as bioelectric wonders, taking the absorbed light and, like an alchemist of the natural world, converting it into electrical energy.

This is no mere fairy tale but the conclusion of astute observation. Scientists, intrigued by the hornet’s propensity for activity during the searing high noon—while its peers sought the shade—set out to unravel the mystery. It was antithetical behavior for a hornet, as these creatures typically eschew the zenith of the sun’s tyranny.

Laboratory studies and analyses illuminated the truth. As the sun climbs its daily peak, the Oriental hornet’s activity surges. It is during these sweltering hours that the hornet channels the solar power to fuel its flight and work. The energy, harnessed from the very star that sustains life on Earth, now powers the sinew of this small insect. The Oriental hornet has morphed into a biological solar cell, the only known animal to claim genuine solar power as its birthright.

This astonishing discovery has swelled beyond the confines of entomological circles into the broader imagination. The Oriental hornet’s solar abilities have challenged what was once considered the exclusive domain of plants and some bacteria. The wonder lies not just in the what, but in the how—a creature has morphed into harnessing power not from the food it consumes or the sheer by-product of living, but directly from the source of all light and life itself.

In this extraordinary tale, the Oriental hornet stands as a paragon of possible futures, an emblem of sustainable power. Whether this narrative will one day inspire human innovation or remain an envied anomaly of natural selection, the wonder it stirs is no less potent. The comic book heroes of our childhoods, passed on from generation to generation, clad in bright colors and gifted with powers beyond the mundane, may have found their match in the reality of this miniature but mighty avenger of the natural world—the solar-powered Oriental hornet.

Guiana dolphins (Sotalia guianensis)

Pin

Pin Beneath the serene blue waves of the Guiana coastline, dolphins cut through the water with athletic grace. These denizens of the deep are the Guiana dolphins, creatures that partake in an aquatic ballet that fascinates and charms onlookers. At first glance, one might simply admire their playful antics and sociable nature, but the story of these cetaceans is written in the intricate details of their biology and evolution.

The origins of the Guiana dolphin hint at a transition from land to sea, a tale tucked away beneath the smooth surface of their skin. In their infancy, a remnant of their terrestrial ancestry is revealed—whiskers. These tactile hairs, born of a time when the ancestors of dolphins roamed the earth’s terrains, adorn the snouts of the young, hinting at a story that stretches back millions of years.

With time, the young dolphins shed these hairs as one discards relics of a former self, but the legacy of the whiskers endures. The tiny pits that cradled these sensory bristles, known as vibrissal crypts, evolve into sophisticated tools of perception. As the whiskers fade away, these crypts become conduits for a different kind of sense, one that harks back to the ancient and enigmatic sense of electroreception.

Each crypt, now an empty chamber, tells its part in this grand narrative of evolution. Surrounded by a network of capillaries and intricately connected to the trigeminal nerve—the same nerve that carries whispers of touch from the face to the human brain—the crypts become the dolphin’s means to “see” in a world where vision cannot always penetrate.

The stillness underwater, the murmur of the current, the dance of particles around. In such a space, the Guiana dolphin swims, guided not just by sight but by the electric portraits that life beneath the waves paints. Hidden prey that once could rely on the cloak of seabed or murky water finds this veil pierced by the electric sense of the dolphin. Through the medium of specialized gel within the receptors, the faint electric fields emanate from living beings are detected, unveiling shadows of life in the dolphin’s mind.

Each electric signal, be it feeble or strong, is captured by the crypts, translated into a language of impulses, and conveyed to the awaiting brain. Here, in the control center, the dolphic computer interprets the echoes of electric voices, constructing an ethereal image of the world where the dolphin’s prey hides. With deft precision and the stealth only centuries of adaptation can craft, the Guiana dolphin navigates and hunts, a mammal shaped by ancient whispers, utilizing a sense lost to many but preserved in the depths where it continues its age-old hunt. And thus, the story of the dolphin’s past is ever-present, playing out each day in the life of these remarkable creatures

Spiders (order Araneida or Araneae)

Pin

Pin In the quiet hours of the night, under the gentle caress of a sliver of moonlight, the garden becomes an orchestra of whispering leaves and the scuttling of hidden life. The world is unaware of the diligent artisans at work, the architects of the most delicate traps known to nature — spiders. Employing an ancient craft passed down through countless generations, they weave not just silk, but the very fabric of life and death in the nooks and crannies of the world.

A single spider, legs balletic and purposeful, labors tirelessly. Each thread it spins is a lifeline and a weapon, an amalgamation of nature’s finesse and savage law. But this particular web, spun from the spinnerets of the arachnid, is imbued with more than just structural ingenuity. It’s coated with a substance far more remarkable than the silk itself — a type of glue, a gift of evolution that serves as a testament to nature’s inventiveness.

This glue, hardly discernible to the naked eye, is a marvel. It possesses an almost magnetic charm for the charged particles that dance restlessly in the air. It’s not just a passive adhesive, it’s an active predator, a siren song for the unwitting pests that flit through the night. The charged particles on the wings and bodies of flying insects respond, drawn in like iron filings to a magnet, unaware of the doom that awaits them.

The spider’s web, seemingly inanimate, is eternally alive with hunger. At the hint of a nearby vibration, it is as if the web breathes, shivering forward ever so slightly, reaching out. An insect’s proximity amplifies these movements; the web quivers in anticipation, bending and shifting, coaxing the air around it to deliver its next meal. It’s a dance of death, choreographed by static forces and the spider’s ingenuity.

But the web’s role isn’t confined to the demise of insects alone. As the weaver slumbers or awaits its prey, its creation partakes in a silent cleansing of the world. The same charged glue that ensnares flying nectar-seekers and nuisance-bearers alike is also predisposed to capturing another invisible threat — airborne pollutants. Dust, smoke, and microscopic fragments of the urban sprawl are all fair game for the spider’s sticky snare. These webs become accidental purifiers, filtering the air in a tireless effort that goes largely unnoticed by the dwellers of the household it protects.

Thus, in the grand tapestry of life, spiders weave more than meets the eye. Theirs is a tapestry that snares the unwelcome, that cleanses the air, and ensures, in the quiet unseen corners of our homes and gardens, a balance is kept. These guardians in the shadows perform a thankless task, an eternal service to the natural order. And so, the spider continues to spin, with each thread a note in an unseen symphony, a delicate strand in the intricate web of life.

Geckos (Hemidactylus frenatus)

Pin

Pin In the tranquil remoteness of a verdant rainforest, where the whispers of leaves form an orchestra with the patter of rain, there moves a creature with an almost magical finesse. Like a miniature superhero from the pages of a comic book, the gecko, small in stature yet majestic in its abilities, confronts the sheer face of a water-kissed leaf or the smooth, unyielding surface of a human habitation. Observers, fueled by curiosity, have long marveled at this reptilian wonder’s capacity for defiance against the fundamental laws of gravity.

But what is the secret behind the gecko’s extraordinary ability to scale the vertical planes that seem to repel all others? It’s a phenomenon not of fiction, but one firmly rooted in the marvels of the natural world, poised on the infinitesimal tips of the gecko’s toes.

Each foot of this agile lizard is an evolutionary masterpiece, equipped with hundreds of thousands of tiny bristles called setae. These setae, much like the bristles of a soft brush, are so minuscule that they delve into the realm of the microscopic. Yet, each one branches out into even finer structures known as spatulae. It is here, on this almost immeasurable scale, that the gecko’s secret resides.

When the gecko places its toe on any surface, these spatulae employ the power of the van der Waals force – a type of electrostatic force that emerges from the subtle and temporary redistribution of electrons around the atoms of any two touching surfaces. It means that every spatula, when in intimate proximity with a surface, experiences a kind of attraction; an electron ballet that allows for an adhesive force strong enough to support the gecko’s weight, yet delicate enough to release as the foot peels away for the next step.

As it happens, this adhesion requires no liquids, no suction, and no residue. It is purely the consequence of an atomic dance, inducing an electrostatic attraction between the gecko’s foot and the climbing surface, making the gecko’s locomotion a spectacle of physics as much as it is of biology.

Imagine the wonder then, when this reptile, no larger than the palm of a hand, scales a pane of vertical glass, it seems to mock the very concept of up and down. The gecko does not ponder the impossibility of its actions. It simply moves, assured by millions of years of evolutionary design that at each step, the invisible forces of nature will keep it firmly glued to its path.

Thus, the gecko continues to climb in this silent, secret ballet, perpetually anchored, even as it defies the pull of the earth beneath it. Each toe-pad contact with the climbing plane is a testament to the power held within the minuscule and the mundane. And so the gecko, with Spider-Man agility, unassumingly demonstrates that sometimes, the wall itself becomes a pathway, for those equipped to walk it.

Sharks (Selachimorpha)

Pin

Pin Beneath the surface of the deep, shimmering blue, a predator lurks, gliding through the water with an ancient and silent grace. It is the shark, a creature both feared and revered, perfected by millions of years of evolution to become one of the ocean’s most formidable hunters. Central to its arsenal of senses is an almost otherworldly ability, one that allows it to detect the faintest whispers of life in the vast and shadowy depths: the ampullae of Lorenzini.

These specialized receptors are a marvel of nature’s design, embedded within the shark’s snout, an array of jelly-filled pores that dot its skin like stars in a midnight sky. They are the shark’s sixth sense, tuned exquisitely to pick up on the electric fields that ripple through the water, fields generated by all living creatures. Every twitch of a muscle, each beat of a heart, sends out a symphony of electrical impulses, invisible to the eye, silent to the ear, but to the shark — a signal as clear as day.

In the abyss, where light dares not tread and where the silence is as heavy as the water that presses in from all sides, the ampullae of Lorenzini come into their own. Here, prey is cloaked in darkness, hiding among rock and reef, or mimicking the innocuousness of the seabed. Camouflage may fool the eye, and stillness may pass in silence, but nothing can mask the electrical aura of life.

A shark, hunting in these enigmatic waters, opens a window into a hidden world with its electrically tuned perception. What seems to us a barren and featureless expanse of water is, for the shark, a landscape alive with signals and tells. A flounder, buried in sediment with only the faintest outlines visible, cannot elude the shark’s extraordinary sense. To the shark, the flounder’s attempt at stealth merely paints a bullseye upon it, for every movement, no matter how subtle, reverberates through the water and into the keenly attuned detectors that line the hunter’s snout.

One might marvel at how the shark, solitary and serene, floats through the open sea. Its eyes may scan for the silhouettes of prey against the sparse light from above, its nostrils may sample the currents for the scent of blood or carrion, but it is with the ampullae of Lorenzini that the shark truly sees its world. No murk can obscure its vision; no distance within range can provide sanctuary.

As the shark approaches its unsuspecting quarry, it exemplifies the cutting edge of nature’s ingenuity. The dance of predator and prey nears its inevitable conclusion, not with a furious chase, but with the quiet inevitability of a fate long decided by the unparalleled senses bestowed upon this ancient mariner. The shark, with the guidance of its ampullae of Lorenzini, affirms its place as the sovereign of the sea, an apex predator in a world where sight is secondary and electric fields tell the tales of the hidden and the hunted.

Conclusion

These electric animals are truly astounding, combining the wonders of biology and physics to survive and thrive in their respective environments. They remind us that even though we harness electricity for our daily needs, in the wild, it’s a natural tool for some of the most unique creatures on Earth. As always, it is critical to respect wildlife and maintain a safe distance, especially with those that pack a powerful electric punch!

FAQs - Shocking Wonders: The Top Electrifying Animals That ZAP You With Awe!

Numerous animals can generate electric shocks, the most famous being electric eels, electric rays, and certain species of catfish. Other less-known electrifying creatures include the electric stargazer fish, certain types of sharks, and even some species of beetles.

Electric eels generate electricity using specialized cells called electrocytes. These cells work much like batteries, arranged in series and stacked end to end. When the eel decides to discharge, these cells create a sudden voltage difference, resulting in an electric shock.

Most electric shocks from these animals are not harmful to humans and might feel like nothing more than a mild tingle. However, the electric eel can produce a substantial shock of up to 600 volts, which can be dangerous and cause serious harm or even death to an unwary human.

Generally, electric animals use their shocking ability as a defense mechanism or to stun prey, not for aggression. They typically avoid humans and will not attack unless provoked or threatened.

Animals like electric eels use their shocks to stun or paralyze prey, making it easier to capture. The sudden electricity disrupts muscular control, rendering the prey immobile long enough for the predator to consume it.

No, the voltage can vary widely between species. Some rays deliver only a gentle jolt, while others can produce a much more potent shock, with some capable of generating voltages up to 220 volts.

No, electric shocks from animals require water or a direct contact medium to conduct electricity. You cannot be shocked by these animals through the air.

Yes, while it is less common, some terrestrial creatures produce electric shocks. One example is the electric ant, also known as the “shock ant,” which can deliver a small, charged defensive jolt.

Researchers use insulated equipment and take careful measures to avoid direct contact with the animals when possible. They may also anesthetize the animals temporarily during handling to ensure both the safety of the animal and the researchers.

Yes, some animals, like the electric eel, have some degree of control over the intensity and frequency of their shocks. They can deliver a range of shocks, from faint pulses for navigation and communication to powerful jolts for defense or hunting.