Pin

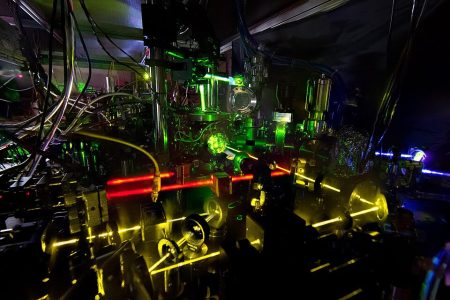

Pin Ytterbium lattice clock that uses photons to measure time precisely / Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Synopsis: Time governs everything in our modern world, from GPS navigation to stock markets. But who decides what time it actually is? Scientists around the globe maintain incredibly precise atomic clocks that define the world’s official time standard. These remarkable devices measure time by counting the vibrations of cesium atoms, achieving accuracy that would only drift by one second every 300 million years. This extraordinary precision keeps our interconnected digital systems synchronized and functioning properly.

For thousands of years, people watched the sun crawl across the sky and called that a day. They noticed the moon’s phases and named that a month. Simple enough. Then civilization got complicated, trains needed schedules, and suddenly knowing the exact hour mattered more than anyone expected.

Today’s world runs on split-second timing that would boggle the minds of our ancestors. When someone checks their phone’s GPS or sends money across the internet, they’re relying on clocks so accurate they make a Swiss watchmaker look downright careless. The difference between good timekeeping and great timekeeping can mean the difference between a successful bank transaction and financial chaos.

The most accurate time in the world doesn’t come from any single clock sitting in a vault somewhere. Instead, it emerges from a democratic process involving hundreds of atomic clocks scattered across the planet, all voting on what second it happens to be. The whole system operates with a precision that borders on the absurd, and yet modern life depends on every tick.

Table of Contents

The Atomic Clock Revolution

Back in 1967, scientists made a decision that changed timekeeping forever. They stopped defining a second based on Earth’s rotation and started using atoms instead. The reason was simple enough—our planet wobbles like a slightly drunk dancer, speeding up and slowing down in ways that make precise measurement impossible.

The atomic clock they settled on uses cesium-133 atoms, which vibrate at a remarkably stable frequency. When left undisturbed, these atoms oscillate exactly 9,192,631,770 times per second. That number isn’t random; it’s now the official definition of one second. Scientists chose cesium because it behaves predictably, doesn’t get moody with temperature changes, and can be reproduced in laboratories worldwide.

These clocks work by detecting the microwave radiation that cesium atoms emit when they jump between energy states. Every time the detector counts 9,192,631,770 oscillations, one second has passed. The beauty of this system lies in its consistency—cesium atoms in Tokyo behave exactly like cesium atoms in Paris, which means everyone’s measuring time with the same ruler.

How Atomic Clocks Actually Work

The inner workings of an atomic clock would make Rube Goldberg proud, though every complication serves a purpose. The process begins when scientists heat cesium metal until it vaporizes into a beam of atoms. This beam then travels through a series of magnetic fields that sort the atoms based on their energy states, keeping only the ones in the right condition for measurement.

Next comes the clever part. The sorted atoms pass through a microwave cavity tuned to exactly 9,192,631,770 hertz. When the frequency matches perfectly, the cesium atoms flip their energy state in a process called resonance. A detector at the end of the line counts these flips, and when it reaches the magic number, the clock ticks forward one second.

The whole apparatus gets surrounded by layers of magnetic shielding to block interference, temperature controls to prevent thermal drift, and vacuum chambers to eliminate air molecules that might bump into the cesium atoms. All this fussing around achieves accuracy that staggers the imagination—these clocks would lose less than one second if they ran for 300 million years straight.

The Global Timekeeping Network

No single atomic clock keeps the world’s official time. Instead, more than 400 atomic clocks in 80 laboratories across the globe contribute their individual measurements to a collective effort. These clocks belong to national measurement institutes, and they each get a vote in determining what time it actually is.

The Bureau International des Poids et Mesures, a French organization with a name longer than some of their measurement intervals, collects data from all these clocks monthly. Their computers then calculate a weighted average called International Atomic Time, or TAI. The weighting matters because not all atomic clocks perform equally—some laboratories maintain more accurate instruments than others, and those get more influence in the final calculation.

This democratic approach protects against catastrophe. If one clock malfunctions or a laboratory loses power, the global time standard barely notices. The system assumes that while individual clocks might drift or fail, the average of hundreds of independent measurements will remain reliable. It’s timekeeping by committee, and it works remarkably well.

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

International Atomic Time would work perfectly if Earth cooperated, but our planet has other ideas. The rotation that gives us day and night gradually slows down due to tidal friction with the moon. Left unchecked, atomic time and solar time would drift apart, and eventually noon would happen at midnight, which would confuse everyone terribly.

To solve this problem, scientists created Coordinated Universal Time, which takes atomic precision and occasionally adjusts it to match Earth’s rotation. About every 18 months on average, timekeepers add a leap second to UTC, inserting an extra tick at midnight on either June 30th or December 31st. This keeps atomic clocks synchronized with astronomical observations.

The leap second system annoys computer programmers and pleases astronomers, which tells you everything about the compromise involved. Some systems handle the extra second gracefully, while others crash spectacularly. There’s ongoing debate about abandoning leap seconds entirely and letting atomic time drift away from solar time, but for now, the tradition continues.

Why Such Precision Matters

The modern world couldn’t function without nanosecond-level time accuracy. GPS satellites, for instance, broadcast signals that include precise timestamps. Your phone receives signals from multiple satellites and calculates your position by measuring tiny differences in arrival times. If those satellite clocks were off by even a microsecond, your navigation would be wrong by about 300 meters.

Financial markets depend on accurate timestamps to determine which stock trade happened first. When two orders arrive at nearly the same instant, the difference of a few microseconds can mean millions of dollars. High-frequency trading systems now synchronize their clocks to within microseconds of UTC, and regulators require detailed time records to prevent cheating.

Telecommunications networks use precise timing to coordinate how they share bandwidth and route data. The internet itself relies on synchronized clocks to maintain connections and prevent data packets from arriving out of order. Even your cellphone tower uses atomic clock accuracy to manage the thousands of simultaneous calls and data streams it handles every second.

The Next Generation - Optical Atomic Clocks

Scientists never rest on their laurels, and while cesium clocks remain the official standard, newer optical atomic clocks make them look positively prehistoric. These devices use laser light instead of microwaves and measure oscillations of strontium or ytterbium atoms at frequencies around 500 trillion cycles per second.

The higher frequency means better precision. Current optical clocks achieve accuracy that would only drift by one second in 15 billion years—longer than the universe has existed. They’ve become so sensitive that they can detect tiny differences in the passage of time based on height above sea level, confirming Einstein’s prediction that time flows differently in different gravitational fields.

These clocks remain experimental and haven’t replaced cesium as the official standard yet. The transition requires international agreement and standardized procedures that take years to establish. But eventually, the definition of a second will likely change again, based on optical transitions instead of microwave frequencies, pushing human timekeeping to even more absurd levels of precision.

Measuring Time in Extreme Places

Maintaining accurate time in space presents unique challenges. GPS satellites carry multiple atomic clocks, but they orbit Earth at speeds where Einstein’s relativity comes into play. Special relativity says their clocks should run slower due to their velocity, while general relativity says they should run faster because they’re farther from Earth’s gravitational field.

The general relativity effect wins out. Satellite clocks actually tick about 38 microseconds faster per day than identical clocks on the ground. Engineers program the satellite clocks to run at a slightly different rate to compensate for this difference. Without these relativistic corrections, GPS navigation would accumulate errors of about 10 kilometers per day.

Deep space missions face even tougher timing problems. Light takes several minutes to travel between Earth and Mars, making real-time communication impossible. Spacecraft carry their own atomic clocks and must make decisions independently, trusting their timekeeping to coordinate actions with Earth-based commands that were sent hours earlier.

The Human Factor in Perfect Time

Despite all the sophisticated machinery, humans still play crucial roles in maintaining global time standards. Operators monitor the atomic clocks constantly, checking for drift or malfunction. They adjust environmental controls, perform maintenance, and occasionally rebuild entire clock systems when better technology becomes available.

The people who run these time laboratories take their responsibility seriously. A single error could disrupt GPS navigation, crash financial markets, or interfere with scientific experiments worldwide. Most laboratories maintain multiple redundant systems and cross-check their measurements against other institutes regularly to catch problems before they spread.

There’s also an art to it. Experienced operators learn to recognize subtle patterns in how their clocks behave. They notice when seasonal temperature changes affect the building’s structure enough to influence measurements, or when electromagnetic interference from nearby construction creates anomalies in the data. Machines provide the precision, but human judgment keeps the system honest.

Time and the Internet

Network Time Protocol keeps computers around the world synchronized to within milliseconds of UTC. The system operates in layers, with the most accurate atomic clocks at the top providing reference time to thousands of secondary servers, which then distribute time to millions of devices below them.

Every time a computer connects to the internet, it checks what time it should be and adjusts its internal clock accordingly. This happens automatically and invisibly, but it prevents the chaos that would ensue if every device kept its own time. Email timestamps, file creation dates, security certificates, and countless other digital functions depend on reasonably accurate shared time.

The protocol itself uses clever mathematics to account for the variable delays that occur when time information travels across networks. It measures how long messages take to travel in both directions and estimates the true time by accounting for this network latency. The system isn’t perfect, but it works well enough that most people never think about it.

The Cost of Precision

Building and maintaining an atomic clock costs serious money. A research-grade cesium clock runs about half a million dollars, while the cutting-edge optical clocks can exceed ten million. Then there’s the infrastructure—specialized buildings with temperature control, vibration isolation, electromagnetic shielding, and backup power systems.

National measurement institutes justify these expenses because accurate time underpins so much economic activity. The GPS system alone generates hundreds of billions of dollars in economic value annually, and it depends entirely on atomic clocks. Studies estimate that a single day without synchronized time would cost the global economy tens of billions of dollars in disrupted services.

Smaller organizations can access accurate time without building their own atomic clocks. They receive time signals from GPS satellites, connect to network time servers, or subscribe to commercial services that provide traceable time references. This democratizes access to precision timekeeping, letting even small companies synchronize their operations to nanosecond accuracy.

FAQs

Yes, individual atomic clocks can drift or malfunction. That’s why global time uses an average of 400+ clocks. If one fails, the others compensate automatically.

Not really. They count atomic oscillations continuously rather than ticking. The “tick” happens mathematically when the count reaches 9,192,631,770 vibrations.

They’re too new and complex. Changing the official second requires international agreement and ensuring labs worldwide can reproduce the measurements reliably.

Clocks either pause for one second or count 60 seconds instead of 59. Some systems spread the adjustment across hours to avoid crashes.

Modern civilization would struggle badly. GPS would fail, markets would chaos, and telecommunications would degrade within hours without precise time synchronization.