Pin

Pin Courtesy of Erik Tanghe from Pixabay

Synopsis: The notion that octopuses might be extraterrestrial has gained surprising traction in recent years. These eight-armed cephalopods possess biological features so extraordinary they challenge our understanding of typical animal life: copper-based blue blood, three separate hearts, and the rare ability to edit their genetic code on demand. Internet communities debate their cosmic origins while marine biologists work to understand their evolution. The scientific explanation for their unusual traits offers insights into how life adapts to extreme ocean environments across millions of years.

Social media platforms regularly feature claims about octopuses being visitors from outer space. These posts accumulate millions of views, sparking genuine curiosity about whether Earth’s oceans harbor extraterrestrial life. The theory persists because octopuses genuinely possess characteristics that seem incompatible with life as most people understand it.

Consider their physical capabilities for a moment. An octopus can navigate through openings barely larger than its eyeball because it lacks any rigid skeletal structure. The animal changes its skin color and texture within fractions of a second, creating patterns more complex than any television screen. Its distributed nervous system means each arm can operate semi-independently, solving problems while the brain handles other tasks. Some species produce venom potent enough to paralyze prey many times their size, while others demonstrate problem-solving abilities that rival some mammals.

The biological mechanisms behind these abilities present genuine puzzles for researchers. When scientists sequenced the octopus genome in 2015, they discovered genetic arrangements unlike those found in most other animals. This discovery, combined with their radically different body plan and cognitive abilities, gave the alien theory unexpected credibility among non-specialists. Understanding what actually happened requires examining how evolution operates in deep ocean environments, where survival demands innovation and where conventional strategies often fail. The real explanation connects geology, chemistry, and adaptation in ways that illuminate how our planet creates diversity without any need for extraterrestrial intervention.

Table of Contents

The Blue Blood That Started the Mystery

Pin

Pin Courtesy of sandrine RONGÈRE from Pixabay

Octopuses pump blue blood through their bodies, and this single fact has probably generated more alien theories than any other characteristic. The color comes from hemocyanin, a copper-based molecule that transports oxygen through their circulatory system. Most animals on Earth use hemoglobin, an iron-based compound that turns blood red.

This fundamental difference exists for practical reasons rooted in ocean chemistry. Copper-based blood works more efficiently in cold, oxygen-poor water where these creatures evolved. The deep ocean contains less dissolved oxygen than surface waters, and temperatures hover just above freezing in many regions where octopuses thrive. Hemocyanin binds and releases oxygen more effectively under these conditions than hemoglobin would.

The evolutionary split between hemoglobin and hemocyanin happened hundreds of millions of years ago when early ocean animals faced different environmental challenges. Some lineages developed iron-based systems, while others refined copper-based solutions. Neither approach is inherently alien—both represent successful adaptations to specific conditions. Horseshoe crabs and many arthropods also use hemocyanin, though they receive far less attention in extraterrestrial speculation.

Three Hearts Working in Concert

Pin

Pin Courtesy of SFU Science Alive (Facebook)

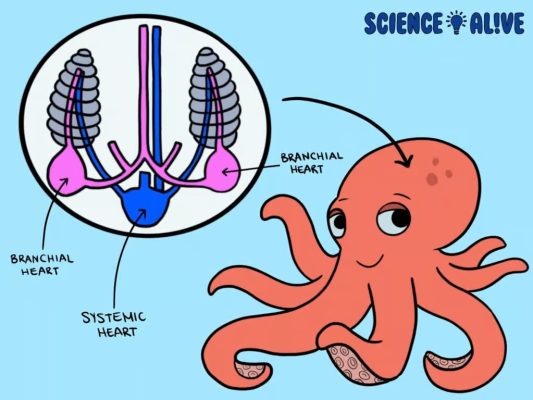

An octopus operates three separate hearts simultaneously, which sounds excessive until you understand the engineering problem they solve. Two branchial hearts pump blood through the gills, where oxygen exchange occurs. The third systemic heart then pushes oxygenated blood throughout the rest of the body.

This arrangement compensates for the inefficiency of hemocyanin compared to hemoglobin. While copper-based blood works well in cold water, it carries oxygen less effectively than iron-based blood does. The extra hearts provide the necessary pressure to keep blood moving at adequate speeds through a system that would otherwise struggle with circulation.

The cardiovascular design also reflects the octopus body plan, which spreads mass across eight flexible arms rather than concentrating it in a compact torso. Moving blood efficiently through this distributed architecture requires more pumping power than a single heart could provide. Marine biologists have documented similar multi-heart systems in other cephalopods, including squid and cuttlefish, all of which face comparable physiological challenges in ocean environments.

The Genome That Confused Scientists

Pin

Pin Courtesy of Springer Nature Link

When researchers published the first complete octopus genome, they found something unexpected. The California two-spot octopus possesses around 33,000 protein-coding genes, more than a human being has. The arrangement of these genes differed substantially from patterns seen in other mollusks, leading some to misinterpret this as evidence of extraterrestrial origin.

The genome contains massive expansions in gene families related to neural development and sensory processing. This genetic architecture supports the octopus’s sophisticated nervous system, which contains roughly 500 million neurons distributed throughout its body. The arrangement allows each arm to process sensory information and coordinate movement without constant input from the central brain.

Genetic complexity alone does not indicate alien origin. Many plants possess far larger genomes than animals do—a Paris japonica plant has 50 times more DNA than a human. Genome size and organization reflect evolutionary history and functional requirements rather than cosmic origins. The octopus genome reveals how evolution can reorganize existing genetic material to produce radically new body plans and capabilities within Earth’s biological framework.

RNA Editing Abilities That Seemed Impossible

Octopuses and their cephalopod relatives perform RNA editing at rates far exceeding those of other animals. This process involves modifying genetic instructions after they leave the DNA but before cells use them to build proteins. The editing allows octopuses to fine-tune their biochemistry in response to environmental changes, particularly temperature fluctuations in ocean water.

Research published in 2017 showed that octopuses edit their RNA in ways that slow down evolution at the DNA level. They apparently trade long-term genetic adaptation for short-term biochemical flexibility. This strategy makes sense for animals inhabiting environments where conditions change seasonally or even daily, requiring rapid physiological adjustments without waiting for genetic mutations to spread through populations.

The discovery startled researchers because few animals use RNA editing so extensively. However, the mechanism itself is not alien—all animals edit RNA to some degree. Octopuses simply developed this existing biological tool into a primary adaptation strategy. The approach carries trade-offs, including reduced genetic diversity over time, but it clearly works well enough to have sustained these animals through millions of years of environmental change.

Intelligence That Defies Expectations

Octopuses solve problems that perplex many vertebrates. Laboratory specimens learn to open childproof containers, navigate mazes, and recognize individual human handlers. Some species use coconut shells or discarded bottles as portable shelters, demonstrating tool use once thought exclusive to primates and birds. This cognitive sophistication seems wildly out of place in an invertebrate.

The explanation lies in convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar traits in response to similar challenges. Octopuses evolved intelligence along a completely different pathway than vertebrates did, yet arrived at comparable results. Their brains organized differently, with more neurons in their arms than in their heads, creating a distributed intelligence network rather than centralized processing.

This independent evolution of intelligence demonstrates that cognitive sophistication can emerge through multiple biological routes. It does not require extraterrestrial intervention—just sufficient evolutionary pressure and time. Crows, elephants, and dolphins each evolved intelligence through different mechanisms as well. The octopus simply represents the most extreme example of this principle, showing that even animals without backbones can develop complex thinking when survival demands it.

The 2018 Study That Sparked Alien Theories

A controversial paper published in 2018 proposed that octopuses might have originated from frozen extraterrestrial viruses that arrived on comets during the Cambrian period. The 33 co-authors suggested this could explain the sudden appearance of complex cephalopods in the fossil record. Media outlets amplified the claim, and it spread rapidly across social platforms despite immediate criticism from the scientific community.

The paper misrepresented both the fossil evidence and the nature of the Cambrian explosion. While cephalopods do appear relatively suddenly in geological terms, this reflects the incomplete nature of the fossil record rather than actual instantaneous appearance. Soft-bodied animals like octopuses rarely fossilize, making their early evolutionary history difficult to trace. The gaps in evidence do not justify invoking extraterrestrial explanations.

Mainstream evolutionary biology rejected the panspermia hypothesis for octopuses because it violated basic principles while solving no actual problems. The genetic, anatomical, and biochemical evidence all points to octopuses evolving from earlier mollusks through conventional natural selection. The paper succeeded primarily in generating headlines rather than advancing scientific understanding, but those headlines gave the alien theory credibility it did not deserve among audiences unfamiliar with paleontology and evolutionary mechanisms.

What the Fossil Record Actually Shows

Cephalopods have existed for roughly 500 million years, with ancestors that included shelled creatures like ammonites and nautiluses. The earliest forms bore little resemblance to modern octopuses, possessing external shells and simpler body plans. Gradual changes over millions of years produced the soft-bodied, highly mobile creatures swimming through today’s oceans.

The transition involved progressive loss of the external shell, which improved swimming efficiency and allowed access to new ecological niches. As the shell disappeared, natural selection favored increased flexibility, better camouflage, and enhanced cognitive abilities for finding shelter and evading predators. Each step provided survival advantages that helped these traits spread through populations.

Fossil evidence supporting this progression exists, though it remains incomplete due to preservation challenges. Soft tissue rarely survives the fossilization process, especially in marine environments where bacterial decomposition proceeds rapidly. Researchers must often infer evolutionary transitions from scattered specimens and comparative anatomy studies. Despite these limitations, the available evidence consistently supports gradual evolution rather than sudden extraterrestrial arrival.

Camouflage Systems More Advanced Than Technology

An octopus can transform its appearance in less than one second, matching colors, patterns, and even textures of its surroundings with precision that baffles materials scientists. Specialized cells called chromatophores expand and contract under muscle control, while iridophores and leucophores manipulate light reflection and scattering. The system operates without central coordination, with each patch of skin responding semi-independently to visual input.

This capability evolved as both predator avoidance and hunting strategy. Octopuses lack the defensive shells their ancestors possessed, making them vulnerable to fish, marine mammals, and other threats. Effective camouflage became essential for survival. Simultaneously, the ability to hide in plain sight helps octopuses ambush prey like crabs and small fish.

The sophistication of octopus camouflage emerges from millions of years of selective pressure rather than alien engineering. Each incremental improvement in color-matching or texture simulation provided survival advantages, gradually producing the remarkable system observable today. Cuttlefish and squid evolved similar systems independently, demonstrating that multiple evolutionary pathways can generate comparable solutions when animals face similar environmental challenges.

The Boneless Body Plan

Octopuses possess no skeleton whatsoever except for a small beak made of chitin. This complete absence of rigid structure allows them to squeeze through any opening larger than their beak, reshape their bodies to hide in impossibly small crevices, and move with flexibility unmatched by vertebrates. The trade-off involves losing the structural support that bones provide, requiring powerful muscles to maintain body shape.

This body plan represents an extreme adaptation to life among rocks, coral, and other complex underwater structures where rigid bodies would be a liability. The ability to compress and contort provides both escape routes from predators and access to prey hiding in narrow spaces. The strategy works because water pressure helps support the soft body, reducing some demands that gravity places on land animals.

Evolution produced this design through gradual reduction of the ancestral shell and reorganization of muscular systems. The process did not happen overnight—intermediate forms existed with partial shells or different arrangements of support structures. Natural selection favored configurations that improved survival and reproduction in specific habitats. The final result appears alien because few animals pursue this strategy to such extremes, but the developmental pathway followed ordinary evolutionary mechanisms without requiring extraterrestrial input.

Why Ocean Evolution Produces Strange Creatures

The ocean environment imposes selection pressures vastly different from those on land. Water provides buoyancy, reducing the importance of skeletal support. Cold temperatures and low oxygen levels reward unusual metabolic solutions. Darkness at depth favors bioluminescence and enhanced non-visual senses. These conditions push evolution toward designs that seem bizarre when compared to familiar land animals.

Cephalopods exemplify ocean-specific adaptations more dramatically than most groups, but they are not unique in developing unusual traits. Deep-sea fish display transparent heads, fishing-rod lures made of modified fins, and expandable stomachs for swallowing prey larger than themselves. Jellyfish lack brains entirely yet capture prey effectively. Mantis shrimp see colors humans cannot perceive and strike with acceleration matching bullet speeds.

The octopus becomes less alien when viewed alongside other marine life adapted to similar conditions. The ocean has been evolving complex life for longer than land has, providing more time for diversification and experimentation. The fundamental mechanisms remain the same as terrestrial evolution—mutation, selection, and inheritance—but the different environment guides these mechanisms toward different outcomes. Understanding this context reveals why octopuses seem strange while explaining why they are entirely terrestrial in origin.

What This Teaches Us About Evolution

The octopus demonstrates how evolution can produce intelligence, complex behavior, and sophisticated biology through pathways completely independent of vertebrate development. This reality has implications for how scientists think about life elsewhere in the universe. If Earth’s evolution generated intelligence through at least two radically different routes—vertebrate and cephalopod—then life on other planets might produce cognitive beings through mechanisms we have not yet considered.

The alien octopus theory fails scientifically but succeeds in highlighting how strange Earth’s own biodiversity can be. The traits that make octopuses seem extraterrestrial actually illustrate the creative power of natural selection operating across geological timescales. Each unusual feature traces back to specific environmental challenges and the gradual accumulation of beneficial mutations.

Perhaps the most important lesson is that evolution does not follow a single template. There is no universal form that intelligent or complex life must take. The octopus proves that Earth itself can generate organisms as strange as anything science fiction might propose. When we eventually detect life on other worlds, it may resemble octopuses more than it resembles us—not because octopuses are alien, but because evolution explores every viable solution to survival challenges, producing diversity that exceeds human imagination without ever leaving the planet.

FAQs

Yes, their blood is blue due to hemocyanin, a copper-based oxygen carrier that works better in cold, low-oxygen ocean water than iron-based hemoglobin would.

They edit RNA, not DNA. This lets them adjust protein production quickly in response to temperature changes without waiting for genetic mutations to occur.

Significantly smarter. They solve puzzles, use tools, recognize individual humans, and possess around 500 million neurons distributed throughout their bodies.

Most don’t. One controversial 2018 paper suggested it, but the scientific community rejected the hypothesis as unsupported by genetic and fossil evidence.

Their cephalopod ancestors appeared roughly 500 million years ago. Modern octopuses evolved gradually through natural selection, not extraterrestrial arrival.