Pin

Pin Representative Image / Image by Freepik

There exists in human history a peculiar arrogance, a belief that we might improve upon nature’s design through sheer force of will. Not the careful cultivation of crops or the domestication of animals—no, something far more audacious. Something that makes one pause and wonder at the breathtaking hubris of it all. Scientists in Soviet laboratories attempting to breed humans with chimpanzees. Chinese officials declaring war on birds. Doctors injecting monkey glands into aging men seeking youth. Each episode reads like fiction, yet each occurred, documented in journals and newspapers, witnessed by thousands.

What strikes one most forcefully about these moments is not their scientific ambition but their fundamental misunderstanding of nature’s complexity. When humans tried to play nature, they approached ecosystems and biology as if they were simple machines—pull this lever, push that button, achieve the desired result. But nature, as they discovered, does not bend so easily to human intention. It pushes back. It reveals consequences unforeseen, cascading failures that ripple outward like stones thrown into still water. These are the stories of those attempts, each one a lesson written in ecological disaster or ethical horror.

Table of Contents

1. The Great Sparrow Campaign (1958)

Pin

Pin Great Sparrow Campaign (1958) / Photo from Wikimedia Commons

Mao Zedong, in the spring of 1958, looked upon the fields of China and saw enemies everywhere. Not human enemies, but small brown birds—sparrows, to be precise. They ate grain, he reasoned, and China needed every kernel of rice to feed its enormous population. The logic seemed simple, almost mathematical. Eliminate the sparrows, save the grain, feed the people. And so began one of history’s most catastrophic exercises in ecological manipulation. The entire nation mobilized. Citizens banged pots and pans for days, preventing sparrows from landing until they fell from the sky in exhaustion. Others shot them, poisoned them, destroyed their nests. Within months, sparrow populations plummeted toward extinction.

But nature, as it so often does, had the last word. The sparrows, it turned out, ate something besides grain. They consumed insects in vast quantities—locusts, in particular. Without sparrows to check their numbers, locust populations exploded across China’s farmlands like a biblical plague. The insects devoured crops far more efficiently than any sparrow ever had. Combined with other disastrous policies of the Great Leap Forward, the result was famine. Between fifteen and forty-five million people starved. One thinks of those who banged the pots and pans, believing they were helping their country, unaware they were participants in an ecological unraveling. By 1960, the government quietly imported sparrows from the Soviet Union, a tacit admission that nature’s balance was not theirs to redesign so carelessly.

2. The Human-Ape Hybrid Experiments (1920s)

Pin

Pin The Human-Ape Hybrid Experiments (1920s) / Photo from Wikimedia Commons

In a research station on the coast of French Guinea, a Soviet scientist named Ilya Ivanovich Ivanov pursued what might be the most disturbing experiment in modern biology. The year was 1926, and Ivanov had convinced himself—and apparently the Soviet government—that creating a human-chimpanzee hybrid was not only possible but desirable. One struggles to understand the reasoning, though it seems rooted in a desire to prove evolutionary theory while simultaneously creating a new species that might serve as laborers. He inseminated three female chimpanzees with human sperm. The attempts failed. The chimpanzees did not become pregnant, and perhaps that failure was nature’s mercy.

But Ivanov did not stop there. He returned to the Soviet Union with a new, even more troubling plan. He would inseminate human women with chimpanzee sperm. One thinks of the ethical abyss this represents, the complete abandonment of human dignity in service to scientific curiosity. He found volunteers—five women who agreed, though one wonders what desperation or ideological fervor drove them to such a decision. Before the experiment could proceed, however, Ivanov was arrested during Stalin’s purges in 1930, charged with counter-revolutionary activities. He died two years later in exile. The experiment never happened, though his earlier attempts remain documented in Soviet archives. What haunts one most is not merely the failure of the science, but the willingness to try at all—to treat the boundary between species as merely another obstacle to overcome.

3. The Monkey Gland Affair (1920s)

Pin

Pin The Monkey Gland Affair 1920s / Photo from Wikimedia Commons

Serge Voronoff stood in his Paris clinic in the 1920s, holding what he believed was the key to eternal youth—testicle tissue from chimpanzees and baboons. A Russian-born surgeon working in France, Voronoff had convinced himself that aging resulted from depleted sex glands, and that transplanting thin slices of monkey testicular tissue into human scrotums would restore vigor, vitality, and years to a man’s life. Hundreds of wealthy men, terrified of their own mortality, paid enormous sums for the procedure. By 1930, over five hundred men had undergone the operation in Voronoff’s clinic alone, with thousands more performed by other surgeons who adopted his technique. The promise was intoxicating—youth restored through surgical intervention, nature’s clock turned backward through sheer audacity.

The reality, of course, was quite different. The grafted tissue was rejected by the human immune system, though this was not understood at the time. Any perceived benefits were purely placebo, the psychological boost of believing oneself rejuvenated. But the consequences rippled outward in ways Voronoff never anticipated. The demand for monkey glands was so intense that it threatened primate populations in Africa. Hundreds of chimpanzees and baboons were captured and killed to supply European clinics. By the 1940s, the medical community had thoroughly debunked Voronoff’s claims, and his reputation collapsed into ridicule. Yet one cannot help but feel a strange sympathy for those desperate patients, so frightened of death that they were willing to have ape tissue sewn into their bodies. The boundary between human and animal, it seemed, was negotiable if the price was right.

4. The Dust Bowl Creation (1930s)

Pin

Pin Arthur Rothstein’s Farmer and Sons Walking in the Face of a Dust Storm, a Resettlement Administration photograph taken in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, in April 1936

The American Great Plains had existed for thousands of years as grassland—deep-rooted prairie grass that held the soil together through drought and wind. Then came the farmers in the early 1900s, armed with new mechanized plows and an unshakeable belief that they could transform this semi-arid land into an agricultural paradise. They tore up millions of acres of native grass, planting wheat in its place. The wheat grew well during wet years, and profits soared. More grass was plowed under. More soil was exposed. No one paused to consider what might happen when the rains stopped, as they inevitably do on the plains. The settlers had lived there only decades, but they spoke with the confidence of people who believed they understood the land better than the land understood itself.

The drought began in 1930, and without deep prairie roots to anchor it, the topsoil simply blew away. Massive dust storms, some carrying dirt as far as New York City and Washington D.C., turned day into night across the plains. On April 14, 1935—Black Sunday—a dust cloud two miles high rolled across the region, suffocating livestock and burying homes. Three and a half million people fled, becoming refugees in their own country. The disaster was not natural, not truly. It was manufactured through agricultural hubris, through the belief that nature’s design could be improved upon without consequence. The native grasses had evolved over millennia to survive prairie conditions. Humans, in their wisdom, had decided wheat would be better. The land responded by becoming uninhabitable, teaching a generation that some boundaries exist for reasons we ignore at our peril.

5. The Thalidomide Tragedy (1957-1961)

A German pharmaceutical company called Chemie Grünenthal synthesized a new drug in 1957 and named it thalidomide. It seemed, by all accounts, remarkably safe—a sedative that could calm nerves and ease nausea without the dangerous side effects of barbiturates. Pregnant women, suffering from morning sickness, found it particularly effective. Doctors prescribed it freely across Europe, Australia, and Canada, reassured by studies showing the drug was virtually impossible to overdose on. Here was modern chemistry at its finest, they believed—a gentle remedy for a common ailment, proof that science could improve upon nature’s harsh treatment of expectant mothers. The drug was sold over the counter in Germany, so trusted was its safety profile. Thousands of women took it during their first trimester, grateful for the relief it brought.

Then the babies began to be born. Infants with seal-like flippers instead of arms and legs, a condition called phocomelia that had been extraordinarily rare in medical history. The pattern emerged slowly, terrifyingly—almost every affected child’s mother had taken thalidomide during early pregnancy. By the time the drug was withdrawn in 1961, an estimated ten thousand children worldwide had been born with severe malformations. Thousands more died shortly after birth. The tragedy revealed something medicine had not fully grasped: the developing fetus exists in a delicate chemical balance, and substances that seem harmless to adults can be catastrophic to forming limbs and organs. Nature had established strict parameters for fetal development over millions of years of evolution. Thalidomide, created in a laboratory in less than a decade, had disrupted those parameters with devastating precision. The survivors lived as permanent reminders that human cleverness and natural processes operate on fundamentally different timescales.

6. The Aral Sea Disaster (1960s-2000s)

Pin

Pin Aral Sea Disaster (1960s-2000s) / Photo by envis.maharashtra.gov

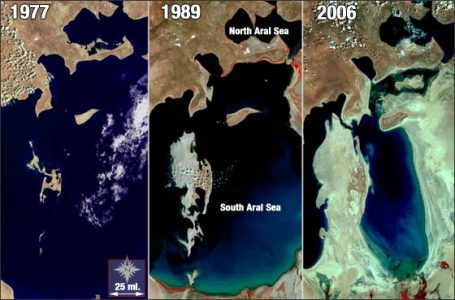

The Aral Sea, nestled between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, was once the fourth-largest lake in the world. Fishermen had worked its waters for centuries, pulling in sturgeon and carp from depths that seemed inexhaustible. Then Soviet central planners looked at the two rivers feeding the sea—the Amu Darya and Syr Darya—and saw waste. All that water flowing into a landlocked lake when it could be diverted to irrigate cotton fields in the desert. Cotton would bring foreign currency, transform the Soviet economy, prove that socialist planning could make even deserts bloom. In the 1960s, they began construction on a massive canal system, siphoning water from the rivers before it could reach the sea. The cotton grew beautifully at first, white fields stretching across former desert. Production soared. The planners celebrated their victory over nature.

But the Aral Sea began to die. Without its rivers, the water level dropped year by year, meter by meter. By 2007, the sea had shrunk to ten percent of its original size, splitting into separate smaller lakes. Fishing villages that once sat on the shore found themselves stranded fifty miles from water, their boats rusting in sand that had been seabed. The exposed lakebed, saturated with agricultural chemicals and salt, created toxic dust storms that spread disease across the region. The local climate changed—summers grew hotter, winters colder, without the sea’s moderating influence. What strikes one most painfully is the fishermen’s testimony, recorded in the 1980s and 90s, describing how they watched the water recede year after year, knowing their way of life was ending but powerless to stop it. The planners had treated an entire sea as if it were surplus to requirements, a miscalculation in nature’s ledger that they could correct. Instead, they created one of the planet’s worst environmental catastrophes.

7. The Cane Toad Invasion of Australia (1935)

Pin

Pin Cane Toad Invasion of Australia (1935) / Photo by Wikimedia Commons

Australia in 1935 faced a problem with beetles. The grey-backed cane beetle, specifically, was devastating sugarcane crops in Queensland, chewing through the plants and costing farmers substantial losses. Agricultural scientists, looking for a solution, turned to Hawaii, where sugar plantations had successfully used cane toads to control similar beetle populations. The toad seemed ideal—large, voracious, breeding prolifically. In June of that year, 102 cane toads were released into Queensland canefields with great optimism. Here was biological control at its finest, the scientists believed. Why use pesticides when nature itself could provide the remedy? The toads would eat the beetles, the sugarcane would flourish, and balance would be restored through clever human intervention.

But the toads had other plans entirely. They ignored the cane beetles, which lived high in the sugarcane where toads rarely ventured, and instead began eating everything else—insects, frogs, small mammals, even pet food left in bowls. More alarmingly, the toads possessed poison glands that killed any predator foolish enough to bite them. Native Australian predators—quolls, goannas, freshwater crocodiles—had never encountered such toxins and died in droves after attacking the toads. The toad population exploded, spreading across northern Australia at a rate of fifty kilometers per year. Today, over 200 million cane toads occupy more than 1.2 million square kilometers of Australia, and their advance continues westward. They have caused local extinctions of native species and fundamentally altered ecosystems across the continent. What haunts one about this disaster is its preventability—had anyone studied the Hawaiian situation more carefully, they would have discovered the toads there never actually controlled beetle populations either. Nature, it seems, resists being conscripted into human plans.

8. The Killer Bee Creation (1956)

Pin

Pin Killer Bee Creation (1956) / Photo by Wikimedia Commons

In the forests of Brazil, a geneticist named Warwick Estevam Kerr had what seemed like a reasonable idea. Brazilian honeybees, descended from European stock, were gentle and produced modest amounts of honey, but they struggled in the tropical heat and were susceptible to local diseases. African honeybees, by contrast, thrived in hot climates and produced honey prolifically, but they were notoriously aggressive. Kerr thought he could breed the best qualities of both—the African bee’s vigor and productivity combined with the European bee’s docility. In 1956, he imported African queen bees to his research facility in Rio Claro, São Paulo, intending to carefully crossbreed them under controlled conditions. The hybrid bees would revolutionize Brazilian agriculture, he believed, creating a super-pollinator perfectly adapted to South American conditions.

Then, in 1957, a visiting beekeeper noticed that Kerr’s experimental hives had excluder screens that prevented the queens from leaving. Thinking this was an oversight, he helpfully removed the screens. Twenty-six African queen bees escaped, along with their swarms, and began breeding with local populations. The resulting hybrids inherited the African bee’s aggression along with its hardiness. These so-called Africanized bees, or killer bees as the press dubbed them, spread northward at an astonishing rate of two hundred to three hundred miles per year. They attacked in swarms when disturbed, pursuing perceived threats for over a quarter mile. Thousands of people and countless animals have been killed by mass stings over the decades since. By 1990, they had reached the United States. What strikes one most about this catastrophe is how a single moment of well-intentioned helpfulness—removing those screens—unleashed consequences that spread across two continents. Kerr himself expressed lifelong regret, though he maintained the bees’ agricultural benefits outweighed their dangers. Nature, it seemed, would not allow humans to cherry-pick only the traits they desired.

9. The Maternal-Infant Health Care Law (1995)

China passed the Maternal and Infant Health Care Law in 1995, a piece of legislation that sounds benign in its title but contained provisions that made eugenicists worldwide take notice. The law mandated premarital medical examinations and gave doctors the authority to recommend delayed marriage or sterilization for people with certain genetic conditions, infectious diseases, or mental illnesses. Couples could be advised—or in some interpretations, required—to use long-term contraception or undergo sterilization if they were deemed likely to produce children with serious hereditary conditions. The government framed this as public health policy, a way to reduce suffering and improve the overall quality of the population. The term used in early drafts was “yousheng”—literally, giving birth to superior quality. Officials spoke of reducing the burden of disability on society, of preventing tragic births, of improving the genetic stock of the nation through scientific management.

The international outcry was immediate and fierce. Geneticists and ethicists worldwide condemned the law as state-sponsored eugenics, uncomfortably reminiscent of programs in Nazi Germany and forced sterilization campaigns in early twentieth-century America and Scandinavia. Under pressure, China amended the law’s language, removing the most explicitly eugenic terminology, but the core provisions remained. Enforcement varied wildly by province, with some regions rigorously implementing screening programs while others largely ignored the mandates. What disturbs one most deeply is not merely the policy itself but the philosophy underlying it—the belief that human reproduction should be managed like crop cultivation, that some lives are worth preventing, that the state possesses both the wisdom and the right to decide who should and should not reproduce. The law remained in effect until 2021, when it was finally repealed. Yet its existence raises questions that linger uncomfortably: where is the line between preventing suffering and preventing people? And who, ultimately, should draw that line?

10. The Biosphere 2 Failure (1991-1993)

Pin

Pin Biosphere 2 Failure (1991-1993) / Photo by Wikimedia Commons

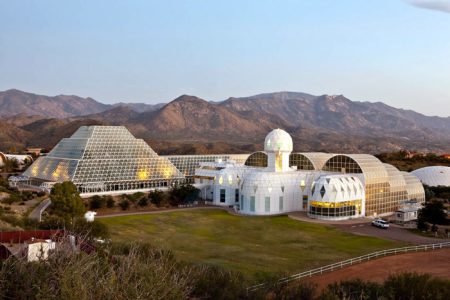

In the Arizona desert, a group of visionaries constructed what they believed would be a self-sustaining miniature Earth. Biosphere 2—the original Earth being Biosphere 1—was a three-acre sealed glass and steel structure containing five distinct ecosystems: rainforest, ocean, savannah, marsh, and desert, along with agricultural areas to feed the inhabitants. In September 1991, eight scientists entered the facility, sealing themselves inside for what was planned as a two-year mission. They would grow their own food, recycle their own air and water, and prove that humans could create closed ecological systems for future space colonization. The structure had cost two hundred million dollars to build, and its backers spoke confidently of replicating Earth’s natural cycles through human engineering. No outside air, food, or water would enter. Nature’s processes, they believed, could be contained and controlled within glass walls.

The facility began failing almost immediately in ways no one had anticipated. Oxygen levels plummeted from twenty-one percent to fourteen percent within sixteen months—low enough to cause symptoms similar to altitude sickness. The crew became sluggish, unable to perform simple calculations, constantly exhausted. Eventually, oxygen had to be pumped in from outside, breaking the sealed environment and invalidating the experiment’s core premise. The cause was eventually traced to microbes in the rich soil, which consumed oxygen faster than the plants could produce it. But that was merely one problem among many. Nineteen of twenty-five vertebrate species went extinct inside the structure.

Morning glory vines and crazy ants proliferated wildly, choking out other plants. Cockroaches multiplied into the millions. The crew, half-starved and perpetually hungry on their limited diet, began fighting among themselves and eventually split into factions that barely spoke. What strikes one most powerfully is the hubris embedded in the attempt itself—the belief that in just a few years of planning, humans could replicate the intricate balance that Earth’s ecosystems developed over billions of years of evolution. The crew emerged in 1993, and while a second mission was attempted, Biosphere 2 never achieved its goal of self-sustainability. Nature, it turned out, was far more complex than even the most sophisticated engineering could capture.

11. The Dengue Fever Mosquito Experiment (2011-Present)

In laboratories across several countries, scientists began breeding mosquitoes infected with a bacterium called Wolbachia. The bacterium, which occurs naturally in many insect species but not in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, has a peculiar effect—it prevents the mosquitoes from transmitting dengue fever, Zika, and other viruses to humans. The plan was elegantly simple: release millions of these Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes into wild populations, where they would breed with native mosquitoes and spread the bacterium through entire populations. Within a generation or two, the theory went, most mosquitoes in treated areas would carry Wolbachia and be unable to transmit diseases that kill thousands annually. Australia began releases in 2011, followed by Indonesia, Brazil, Vietnam, and Colombia. The World Mosquito Program, as it came to be called, spoke of eradicating dengue fever through this biological intervention.

The results have been mixed in ways that reveal nature’s stubborn complexity. In some areas, dengue cases dropped dramatically—Yogyakarta, Indonesia saw a seventy-seven percent reduction. But in other locations, the Wolbachia mosquitoes struggled to establish themselves, or native populations developed resistance. More troubling are the unknown long-term consequences. What happens when you fundamentally alter the biology of a species across entire continents? Mosquitoes are food for birds, bats, and fish—will changing their bacterial composition affect those predators? The experiments continue, expanding to more countries each year. Yet one cannot help but notice a pattern emerging in these stories—each generation believes it has finally mastered the tools to safely manipulate nature, that this time will be different from all the failed attempts before. Which brings us to more recent interventions, where the stakes have grown even higher.

12. The Wuhan Lab Corona Virus and Gain-of-Function Research (2019)

Pin

Pin Wuhan Lab / Photo by The Yomiuri Shimbun/AP

In laboratories around the world, virologists had been conducting what they called gain-of-function research for years—deliberately making viruses more transmissible or more deadly to study how they might evolve naturally and to develop vaccines against future threats. The Wuhan Institute of Virology in China had become one of the leading centers for coronavirus research, collecting samples from bat caves and studying how these viruses might jump to humans. The work was collaborative, involving American funding and international partnerships, all conducted under the banner of pandemic preparedness. Then, in December 2019, patients in Wuhan began arriving at hospitals with a mysterious pneumonia. Within weeks, it became clear that a novel coronavirus—SARS-CoV-2—was spreading rapidly. By March 2020, the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic that would ultimately kill millions and shut down entire economies.

The questions that emerged were perhaps more troubling than the virus itself. Had this pathogen leaked from the laboratory just miles from where the first cases appeared? The Chinese government denied it vehemently, insisting the virus had natural origins in a seafood market. But investigators found peculiarities—the virus appeared remarkably well-adapted to human transmission from the start, and the Wuhan lab had been conducting research on bat coronaviruses, sometimes under biosafety conditions that international observers had previously flagged as inadequate. Documents revealed that researchers there had been proposing to insert furin cleavage sites into coronaviruses—the very feature that makes SARS-CoV-2 so infectious. The debate continues still, with intelligence agencies divided and scientists arguing passionately on both sides. What haunts one most is not knowing—were we victims of a natural spillover, one of those tragic but inevitable moments when a virus jumps species? Or did human ambition to understand and prevent pandemics actually create one? The very research meant to protect us may have unleashed the catastrophe we feared most.

13. Cloud Seeding and the Dubai Floods (2024)

Pin

Pin Cloud Seeding and the Dubai Floods / Photo by Christopher Pike

The United Arab Emirates, sitting in one of the driest regions on Earth, had been manipulating clouds since the early 2000s. The country receives an average of just four inches of rain annually, and every drop is precious. So the government invested heavily in cloud seeding—flying planes into promising cloud formations and releasing silver iodide or salt crystals to encourage water droplets to form and fall as rain. The technology seemed almost miraculous in its early years, coaxing precious rainfall from reluctant skies. By 2024, the UAE was conducting over three hundred cloud seeding missions annually, more than almost any nation on Earth. Meteorologists monitored weather patterns constantly, dispatching aircraft whenever conditions seemed favorable. The program had become so routine, so normalized, that it barely warranted mention in local news. Rain was no longer something that simply happened in Dubai—it was something humans manufactured.

Then came April 2024, when the skies opened with unprecedented fury. In just twenty-four hours, Dubai received more than five inches of rain—more than an entire year’s worth falling in a single day. The city, built for eternal sunshine with inadequate drainage systems, transformed into a network of rivers. The airport flooded, stranding thousands. Cars floated through streets like boats. Shopping malls became indoor lakes. At least one person drowned. The government insisted that cloud seeding had not caused the deluge, pointing to a natural weather system moving through the region. But meteorologists worldwide noted that the UAE had conducted seeding operations just before the storm, and the intensity of the rainfall exceeded anything the natural system should have produced. One thinks of those silver iodide particles drifting through the clouds, each one a tiny catalyst for raindrop formation, and wonders—did human intervention amplify a manageable storm into a catastrophe? The truth remains uncertain, but the event revealed something undeniable: when you regularly manipulate weather systems, you can never quite be sure anymore where nature ends and human interference begins.

FAQs

Yes, in 1958 Mao declared sparrows one of the “Four Pests” and launched a nationwide campaign to eliminate them, leading directly to ecological disaster and contributing to a famine that killed millions.

Absolutely. Africanized honeybees now occupy most of South and Central America and have spread throughout the southern United States since arriving in Texas in 1990, continuing to move into new territories.

Yes, five Soviet women reportedly volunteered in 1929 to be inseminated with chimpanzee sperm, though the experiment was halted before it could proceed when scientist Ivanov was arrested during Stalin’s purges.

The origin remains unconfirmed. The Wuhan Institute of Virology was conducting coronavirus research near where the outbreak began, but definitive evidence for either lab leak or natural spillover remains elusive.

Cloud seeding has been used for decades, but the Dubai 2024 floods raised serious questions. While officials denied responsibility, the unprecedented rainfall following seeding operations suggests we may not fully understand the consequences of weather manipulation.