Pin

Pin Studio Ghibli Scenes / Photo credit – Ghibli Studio

Most animation studios today rely heavily on computers to speed up production and cut costs. Studio Ghibli does things backwards. They still draw everything by hand, which takes forever and costs a fortune, but there’s a reason they stick to this old-school method. When you watch a Ghibli film, you can actually feel the difference – there’s something warmer and more alive about characters that were born from pencil and paper rather than pixels and code.

Minoru Ohashi, one of the studio’s key animators, once said something that really captures what it’s like to work there: “It wouldn’t be surprising if a normal person would lose their temper and quit.” He wasn’t joking. The studio ghibli scenes in animation require such intense attention to detail that animators regularly work themselves to exhaustion. When Miyazaki decided he wanted a specific cloud formation in “The Wind Rises,” his team didn’t just draw some fluffy shapes – they studied meteorology textbooks and spent weeks sketching real clouds from the studio rooftop.

Table of Contents

When Perfectionism Meets Reality

Pin

Pin Yamamori at Studio Ghibli / Photo credit – Ghibli Studio, @framebyframe_animation

Eiji Yamamori learned the hard way what working for Miyazaki really meant. As a background artist, Yamamori thought he understood detail – until he got assigned to paint the landscapes for “The Wind Rises.” Miyazaki wanted every blade of grass to look authentic, every tree branch to bend naturally in the wind. What should have been a straightforward job turned into months of research trips to actual Japanese countryside locations, studying how different seasons affect plant growth and how morning light changes throughout the day.

The breaking point came when Miyazaki rejected Yamamori’s work for the fifteenth time on a single field scene. Not because it looked bad – it was gorgeous – but because the way the wheat swayed wasn’t quite right for the specific time of year the scene was supposed to represent. Yamamori later admitted he seriously considered walking out that day. But something kept him there, maybe the same thing that keeps all Ghibli artists pushing through the impossible standards: the knowledge that millions of people would eventually see this single scene and feel something beautiful because of all that extra effort.

The Science of Making Magic Look Real

Pin

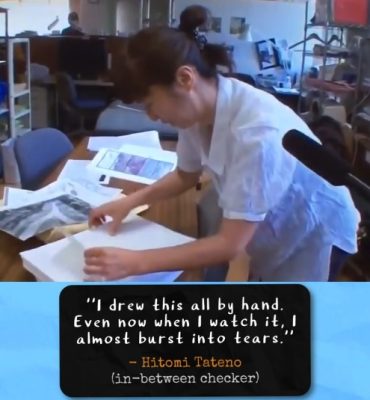

Pin Hitomi Tateno at Ghibli Studio / Photo credit – Ghibli Studio, @framebyframe_animation

Hitomi Tateno joined Studio Ghibli thinking she’d spend her days drawing cute characters and fantastical creatures. Instead, she found herself becoming an amateur physicist. When Miyazaki assigns scenes involving natural phenomena – water flowing, fire burning, wind blowing through hair – he expects his animators to understand the actual science behind these movements. Tateno spent weeks studying fluid dynamics just to animate a single scene of rain hitting puddles correctly.

This scientific approach sounds excessive until you see the results. When Chihiro’s parents transform into pigs in “Spirited Away,” or when Calcifer flickers in “Howl’s Moving Castle,” these magical moments feel believable because they follow real-world physics. Tateno discovered that audiences subconsciously notice when something moves wrong, even in a fantasy setting. A flame that doesn’t behave like actual fire will feel fake, breaking the spell that Ghibli works so hard to create. The studio’s animators don’t just draw what they think looks right – they study how things actually work in nature, then apply those principles to their art, whether they’re animating a realistic airplane or a walking castle with chicken legs.

The Frame-by-Frame Marathon

Pin

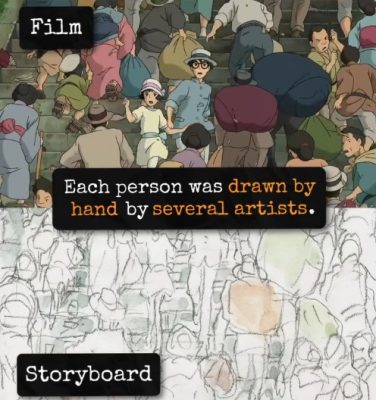

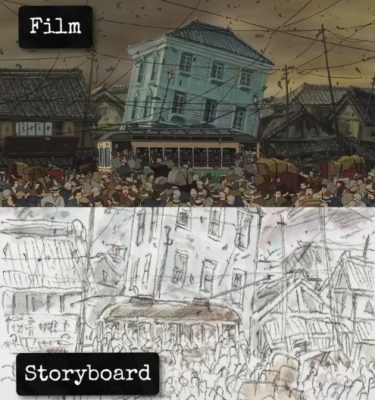

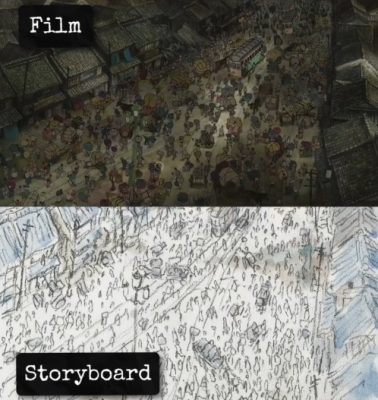

Pin Scene from “Wind Rises” / Photo credit – Ghibli Studio, @framebyframe_animation

Animation operates on a simple but brutal mathematical reality: most films run at 24 frames per second, which means every single second of screen time requires 24 individual drawings. For a typical 90-minute Ghibli film, that adds up to roughly 130,000 hand-drawn frames. But here’s where Studio Ghibli makes things even more challenging for themselves – they often use “ones” instead of “twos,” meaning they draw a new picture for every single frame rather than using each drawing twice like most studios do to save time and money.

This decision transforms every scene into an endurance test. When Miyazaki wanted to show Jiro’s paper airplane gliding through the air in “The Wind Rises,” the sequence lasted only eight seconds on screen. Those eight seconds required 192 separate drawings, each one showing the plane’s position, the way shadows fell across its wings, and how the wind affected its flight path. The animators had to maintain perfect consistency across all 192 frames while making tiny adjustments to show realistic movement. One small mistake in frame 47 could make the entire sequence look jerky or unnatural, forcing the team to start over from the beginning.

The Emotional Weight of Every Pencil Stroke

Pin

Pin Scene from “Wind Rises” / Photo credit – Ghibli Studio, @framebyframe_animation

Animation isn’t just about making things move – it’s about making audiences feel something. At Studio Ghibli, this emotional responsibility weighs heavily on every artist’s shoulders. When Miyazaki assigns a scene, he doesn’t just explain what needs to happen; he describes the exact emotion the audience should experience. For “The Wind Rises,” he wanted viewers to feel the same mixture of wonder and melancholy that Jiro felt while watching his planes soar through the sky, knowing they’d eventually be used in war.

This emotional precision requires animators to become actors with their pencils. They study their own faces in mirrors to understand how sadness changes the curve of an eyebrow, or how genuine joy affects the way someone’s shoulders move when they walk. Miyazaki often acts out scenes himself, exaggerating gestures and facial expressions so his team can capture the subtle body language that makes animated characters feel truly alive. The artists then translate these performances into thousands of drawings, maintaining that emotional authenticity across every single frame. It’s exhausting work that goes far beyond technical skill – it demands that animators pour their own hearts into every character they bring to life.

The Legend Behind the Madness

Pin

Pin Hayao Miyazaki / Photo credit – Ghibli Studio, @framebyframe_animation

Hayao Miyazaki didn’t start out as the demanding perfectionist that his animators both fear and respect today. Early in his career, he worked at other animation studios where shortcuts and compromises were part of the daily routine. But something changed when he co-founded Studio Ghibli in 1985. He’d seen too many beautiful stories ruined by lazy animation, too many moments where audiences could tell that artists had simply given up and done “good enough.” He made a promise to himself that his studio would never settle for mediocrity, even if it meant driving everyone slightly crazy in the process.

This philosophy becomes clearer when you understand Miyazaki’s background. He grew up during World War II, watching his country rebuild itself from nothing through careful craftsmanship and attention to detail. His father managed a factory that made airplane parts, which explains Miyazaki’s lifelong fascination with aircraft and his insistence on mechanical accuracy in films like “The Wind Rises.” For Miyazaki, every frame represents a small piece of cultural heritage that will outlive everyone who worked on it. He pushes his animators so hard because he believes their work deserves the same respect as traditional Japanese crafts like pottery or calligraphy – arts where imperfection is simply not acceptable.

When Traditional Meets Innovation

Pin

Pin Scene from “Wind Rises” / Photo credit – Ghibli Studio, @framebyframe_animation

While Studio Ghibli stubbornly clings to hand-drawn animation, they’re not completely stuck in the past. The studio has developed their own hybrid approach that combines traditional techniques with carefully selected modern tools. For “The Wind Rises,” Miyazaki allowed his team to use computer-generated imagery for some of the more complex mechanical elements – the intricate internal workings of airplane engines, for instance – but only after the digital artists proved they could match the warmth and texture of hand-drawn animation.

This selective use of technology creates a unique visual style that feels both timeless and contemporary. The characters and most backgrounds remain purely hand-drawn, maintaining that organic quality that makes Ghibli films feel so alive. But when Jiro’s prototype aircraft takes flight, computer animation handles the precise mechanical movements while traditional animation focuses on the pilot’s expressions and the emotional impact of the scene. The two techniques blend so seamlessly that most viewers never notice where one ends and the other begins. This careful balance requires constant communication between digital and traditional artists, with Miyazaki acting as the final judge of whether each shot maintains the studio’s exacting standards for both technical accuracy and emotional resonance.

The Breaking Point That Creates Beauty

There’s a specific moment in every Ghibli production when the pressure becomes almost unbearable. Artists call it “the wall” – that point where the workload seems impossible and the standards feel unreachable. During “The Wind Rises” production, this moment came when Miyazaki decided he wasn’t satisfied with how the wind looked in the crucial flying sequences. He wanted audiences to actually see the air currents flowing around the aircraft, not just assume they were there.

The animation team had already spent months perfecting these scenes, but Miyazaki’s new vision meant starting over from scratch. They needed to study aerodynamics textbooks, watch slow-motion footage of wind tunnels, and figure out how to make invisible air currents visible without making them look silly or distracting. Several animators worked 16-hour days for weeks, redrawing the same sequences over and over until they captured the exact balance of scientific accuracy and visual poetry that Miyazaki demanded. Some team members later said this was the closest they’d ever come to quitting, but those same artists now point to these wind sequences as some of the most beautiful animation ever created. The breaking point didn’t break them – it pushed them to discover capabilities they never knew they had.

The Ripple Effect of Obsessive Detail

What happens when an animation studio refuses to cut corners becomes visible in unexpected places. Other animators around the world study Ghibli films frame by frame, trying to understand how the studio achieves effects that seem impossible with traditional hand-drawn techniques. Film schools use “The Wind Rises” as a masterclass in visual storytelling, particularly the flying sequences that took Miyazaki’s team to their breaking point. Students pause the film repeatedly, analyzing how each drawing builds on the previous one to create fluid motion that feels more realistic than many computer-generated effects.

This influence extends beyond animation into live-action filmmaking as well. Directors like Guillermo del Toro and the Wachowski siblings have publicly credited Ghibli’s attention to detail as inspiration for their own work. The studio’s approach to showing weather, natural lighting, and mechanical movements has become a gold standard that other artists aspire to reach. When young animators join other studios, they often bring Ghibli-inspired techniques with them, slowly raising the overall quality of animation worldwide. Miyazaki probably never intended to revolutionize an entire industry when he demanded those perfect wind currents, but that’s exactly what happened. The impossible standards that nearly broke his own team ended up elevating animation as an art form for everyone.

The Human Cost of Animated Perfection

Behind every breathtaking Ghibli scene lies a story of human exhaustion that the studio rarely discusses publicly. The animators who create these masterpieces often work themselves into physical and emotional burnout, sacrificing sleep, social lives, and sometimes their health for the sake of artistic perfection. During the most intensive periods of “The Wind Rises” production, some artists slept at the studio more nights than they went home, surviving on convenience store meals and endless cups of coffee while they redrew the same sequences dozens of times.

The psychological pressure can be just as demanding as the physical workload. When your name appears in the credits of a film that millions will watch and critique, every line you draw carries enormous weight. Animators describe feeling responsible not just to Miyazaki and the studio, but to audiences who trust Ghibli to deliver something extraordinary. This responsibility creates a perfectionism that goes beyond professional pride – it becomes personal. Many former Ghibli artists report that they still dream about unfinished frames years after leaving the studio, their subconscious minds continuing to work on scenes that were never quite perfect enough. The beauty that audiences see on screen represents not just artistic skill, but genuine human sacrifice in pursuit of something greater than entertainment.

The Legacy That Lives Beyond the Studio

The artists who survive the grueling process of creating a Ghibli film often describe it as a transformative experience that changes how they approach their craft forever. Minoru Ohashi, despite his earlier comment about normal people quitting, stayed with the studio for decades and became one of its most respected animators. He credits the impossible standards and relentless revisions with teaching him to see details that other artists miss, to notice the way light behaves in situations most people would overlook. Former Ghibli animators who move to other studios often struggle to adjust to more relaxed environments where “good enough” actually means good enough.

This transformation creates a kind of artistic family tree that spreads Ghibli’s influence far beyond the films themselves. Students who learn from former Ghibli artists carry those lessons to new projects, new studios, and eventually teach the next generation of animators. The techniques developed for scenes like the wind sequences in “The Wind Rises” have influenced everything from video game design to architectural visualization. Miyazaki’s obsessive pursuit of perfection didn’t just create beautiful films – it created a standard of excellence that continues to inspire artists decades later. The human cost was enormous, but the cultural impact reaches far beyond what anyone could have predicted when those exhausted animators were redrawing their frames for the twentieth time.

FAQs

A single second can take weeks or even months! With 24 frames per second and Ghibli’s perfectionist standards, animators often redraw sequences dozens of times before approval.

Absolutely! They research fluid dynamics for water scenes, aerodynamics for flying sequences, and even meteorology for accurate cloud formations in magical settings.

Some scenes in “The Wind Rises” were redrawn over 50 times. The wind current sequences pushed several animators to consider quitting from exhaustion.

Miyazaki believes hand-drawn animation has a warmth and humanity that digital can’t replicate, though they do use limited computer effects for mechanical elements.

Former Ghibli artists bring these techniques worldwide, slowly raising animation quality everywhere. Film schools use Ghibli films as masterclasses in visual storytelling.