Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

In 1965, Singapore stood at the edge of collapse. The island had just been kicked out of Malaysia, leaving two million people stranded on 277 square miles of humid marshland. There was no army worth mentioning, no natural resources to sell, and neighbors who seemed ready to watch the experiment fail. Water had to be imported. Food came from elsewhere. Even the air felt heavy with uncertainty.

Most leaders would have negotiated survival. Lee Kuan Yew chose transformation instead. Over three decades, he turned that vulnerable port into a gleaming financial powerhouse that rivals Switzerland in wealth and efficiency. The man who took office amid riots and racial tension left behind a nation where the rule of law isn’t just respected but expected, where corruption is virtually extinct, and where a once-illiterate population now boasts some of the world’s highest test scores. His methods were often harsh, his critics numerous, but the results became impossible to ignore. This is the story of how one leader’s uncompromising vision built a miracle that geography said shouldn’t exist.

Table of Contents

The Island Nobody Wanted

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

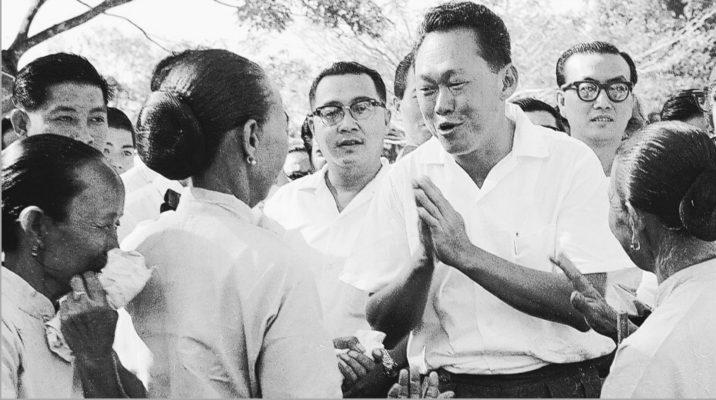

When Singapore separated from Malaysia in August 1965, Lee Kuan Yew wept on national television. Those tears weren’t theatrical—they reflected genuine fear about his country’s survival. The island had been dumped, not liberated. Malaysia’s prime minister had decided that Singapore’s majority-Chinese population would upset the ethnic balance he wanted to maintain. Suddenly, Lee was prime minister of a nation that nobody, including himself, had planned for. The unemployment rate hovered around 14 percent. Housing was desperately inadequate, with families crammed into shophouses and slums. Communal violence between Chinese and Malay residents had bloodied the streets just two years earlier, leaving dozens dead and trust shattered.

The international community offered little hope. Foreign diplomats wrote cables predicting Singapore would collapse within months or perhaps crawl back to Malaysia begging for reunion. The island imported everything from drinking water to eggs, making it hostage to its neighbors’ goodwill. There was no industrial base, no notable exports except rubber and tin transshipment, and a port that faced stiff competition from Hong Kong. Lee surveyed this landscape and made a decision that would define his entire tenure—he wouldn’t manage decline, he would engineer reversal. That choice, made in desperation, set Singapore on a path that would astonish economists and urban planners for generations.

Building an Army from Scratch

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

Singapore’s first existential threat wasn’t economic—it was military. Lee understood that without defense capability, the island would remain forever vulnerable to pressure from larger neighbors. Indonesia had just ended its Confrontation campaign against Malaysia, which included bombing MacDonald House in Singapore and killing three people. Malaysia controlled Singapore’s water supply and could theoretically cut it off during any dispute. Lee needed an army, but he had no military tradition to draw from. The population had no appetite for conscription, and Singapore’s ethnic Chinese majority made China-based military training politically impossible during the Cold War era.

Lee made an unconventional choice that raised eyebrows across Asia—he asked Israel for help. Israeli military advisors arrived quietly in 1965, bringing expertise from a nation that understood existential vulnerability. They helped design a conscription system called National Service that would require every able-bodied male to serve two years in uniform, followed by regular reservist duties until middle age. The pushback was immediate and intense. Young men protested. Families complained. Some fled the country to avoid service. But Lee didn’t blink. He framed military service not as optional civic duty but as the price of citizenship itself. Within a decade, Singapore had transformed from defenseless to disciplined, with a citizen army that could mobilize tens of thousands of trained soldiers within hours. That military foundation gave Lee the security he needed to focus on his next gamble—turning Singapore into something the world had never seen before.

The War on Corruption

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

Lee Kuan Yew inherited a government riddled with the casual corruption that plagued most Asian nations in the 1960s. Police officers expected bribes to process paperwork. Building inspectors looked the other way for cash payments. Low-level bureaucrats supplemented meager salaries by selling favors. This wasn’t considered particularly scandalous at the time—it was simply how things worked across the region. But Lee recognized that corruption functioned like termites in a wooden house, invisibly destroying the structural integrity until everything collapsed. If Singapore wanted foreign investors to trust it with their capital, if citizens needed to believe their government served them rather than exploited them, then corruption had to die completely.

His approach was brutally simple and shockingly effective. First, he raised civil servant salaries dramatically, eventually pegging minister pay to private sector benchmarks. The logic was straightforward—pay people enough that stealing becomes stupid rather than necessary. Then he established the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau with sweeping powers to investigate anyone, including his own political allies and family members. The bureau could examine bank accounts, question suspects without lawyers present, and pursue cases that would make most politicians uncomfortable. Lee backed every investigation publicly, even when it meant prosecuting ministers he’d worked with for years. When his close colleague Wee Toon Boon was caught accepting bribes in 1975, Lee didn’t protect him—he let the courts send him to prison. That signal resonated through every level of government. Within two decades, Singapore ranked among the world’s least corrupt nations, a transformation so complete that leaving your laptop unattended in a café became unremarkable.

Remaking Education into a Weapon

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

In 1965, Singapore’s education system was producing graduates who couldn’t find work that matched their skills. Schools taught in multiple languages—English, Mandarin, Malay, Tamil—but without coordination or quality control. Many children dropped out before finishing primary school because their families needed them to work. The curriculum emphasized rote memorization of facts that had little connection to the economy Singapore needed to build. Lee saw education not as a social service but as the foundation of national survival. If Singapore had no natural resources, then its people had to become the resource—skilled, disciplined, and adaptable enough to attract industries that other countries couldn’t support.

He started by making a controversial decision that still generates debate today. English became the primary language of instruction across all schools, regardless of students’ ethnic backgrounds. This wasn’t about cultural preference—it was cold pragmatism. English was the language of international business, science, and technology. If Singaporean workers could communicate fluently with American executives and British engineers, they’d have advantages that workers in Thailand or Indonesia lacked. Parents protested, especially in the Chinese community where many feared losing their cultural identity. Lee acknowledged the pain but didn’t reverse course. He coupled English instruction with mandatory mother tongue classes to preserve cultural roots while building economic bridges. The system also shifted toward meritocracy with an intensity that bordered on ruthless. Standardized testing identified talented students early, funneling them into elite schools regardless of family wealth or connections. Students who struggled academically got vocational training instead of university tracks. The approach felt cold to some, even heartless, but it created a workforce that multinational corporations competed to hire.

Housing as Nation-Building

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

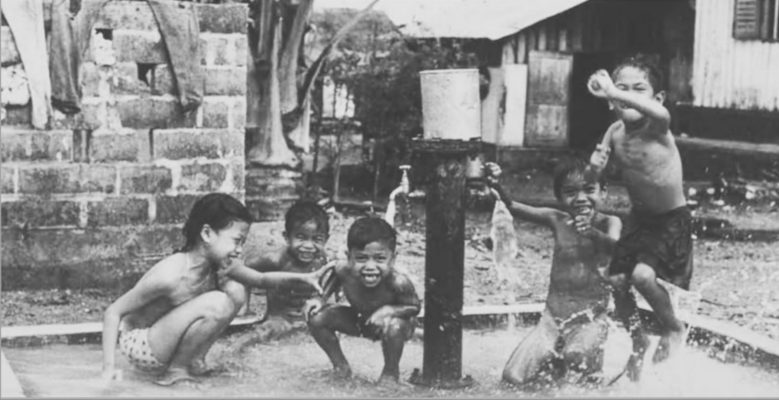

When Lee took power, most Singaporeans lived in conditions that would horrify modern observers. Entire families squeezed into single rooms in crumbling shophouses. Slums sprawled across valuable land near the city center, breeding disease and despair. Landlords charged whatever they wanted because demand so vastly exceeded supply. This housing crisis wasn’t just uncomfortable—it was politically dangerous. People without stable homes don’t develop loyalty to their country. They become vulnerable to radical ideologies promising revolutionary change. Lee understood that if Singaporeans didn’t feel they owned a stake in their nation’s future, that future would remain fragile no matter how fast the economy grew.

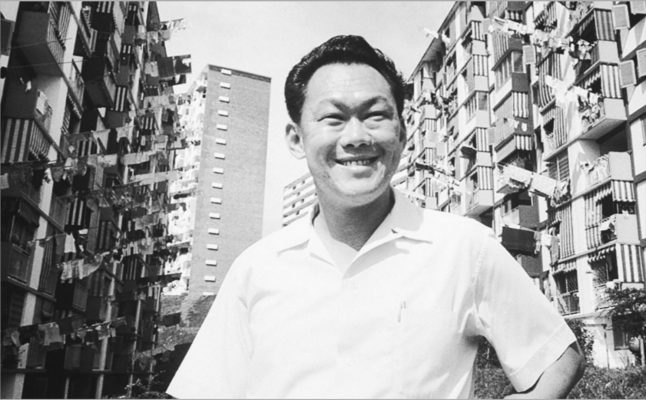

The solution came through an expanded Housing Development Board that would eventually become one of the world’s most ambitious social engineering projects. The government began acquiring land through aggressive compulsory purchase laws, paying compensation but not negotiating endlessly with holdouts. On that cleared land, the HDB built towering apartment blocks at a pace that seemed impossible—sometimes completing a new flat every 45 minutes during peak construction years. But Lee didn’t just want to house people. He wanted to create homeowners who would defend their country because they had something tangible to lose. The government offered generous subsidies and low-interest loans that made purchase affordable for working-class families. It mandated ethnic quotas in each building to prevent the formation of segregated neighborhoods that might reignite racial tensions. Within 25 years, homeownership rates climbed above 80 percent. Those concrete towers, criticized by architects as sterile and repetitive, gave millions of people their first taste of stability, privacy, and investment in tomorrow.

Attracting the World's Money

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

Singapore in the 1960s had nothing that typically attracted foreign investment. The island lacked oil fields, precious metals, or vast consumer markets that might entice multinational corporations. What Lee offered instead was something far more valuable in the long run—predictability. He promised that contracts would be honored, that courts would operate fairly, that infrastructure would work reliably, and that political stability wouldn’t vanish with the next election. These guarantees sound mundane, but they were revolutionary in a region where coups, nationalization, and arbitrary rule changes constantly threatened business operations. Companies that set up factories in Singapore could plan five or ten years ahead without wondering if a new government might seize their assets or change the tax code overnight.

Lee’s team created the Economic Development Board in 1961, even before independence, and tasked it with hunting down foreign companies like a precision sales force. EDB officers flew to America, Europe, and Japan with detailed presentations showing exactly what Singapore offered—educated English-speaking workers, modern ports, reliable electricity, efficient customs processing, and tax incentives structured to reward long-term commitment. When Texas Instruments was considering where to build its first Asian semiconductor plant in 1968, Singapore wasn’t the obvious choice. The company worried about political stability and the tiny domestic market. EDB officers addressed every concern methodically, even arranging meetings with Lee himself to demonstrate government commitment. Texas Instruments chose Singapore, and that decision created a cascading effect. Other electronics manufacturers watched, saw success, and followed. Within fifteen years, Singapore had become a manufacturing hub for products that required precision, reliability, and zero tolerance for corruption or infrastructure failures. The island that imported everything was now exporting billions in electronics, pharmaceuticals, and refined petroleum products.

The Green City That Shouldn't Exist

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

Most developing nations in the 1960s viewed environmental concerns as luxuries they couldn’t afford. Economic growth meant factories, and factories meant pollution—that equation seemed fixed and unavoidable. Lee Kuan Yew rejected that framework entirely, not because he was an early environmentalist in the modern sense, but because he understood psychology and branding. Singapore was tiny, hot, and humid. If it also became dirty and chaotic like many rapidly industrializing Asian cities, why would talented professionals choose to live there? Why would executives relocate their families to a polluted concrete jungle when they could stay in pleasant suburbs back home? Lee decided that Singapore would become a garden, and he pursued that vision with the same uncompromising intensity he applied to corruption and education.

The transformation started with something as mundane as cleaning up rivers. The Singapore River and Kallang Basin had become open sewers where hawkers dumped waste and pig farms discharged effluent directly into the water. The stench was overwhelming. Lee ordered the river cleaned regardless of cost or complaints. Pig farmers and street hawkers were relocated, compensated but not given veto power over the project. Then came the trees—millions of them planted along every major road, in every housing estate, around every industrial park. Lee personally reviewed landscaping plans and rejected designs he considered inadequate. He pushed for laws requiring developers to replace greenery they destroyed during construction. When builders complained about the expense, he didn’t negotiate. The tree-planting campaign was so aggressive that Singapore’s green cover actually increased even as its population exploded. Foreign visitors began noticing that this tropical island felt different—cleaner, more organized, almost surreally well-maintained. That reputation became a competitive advantage worth billions in tourism and talent attraction.

Water Independence Through Sheer Will

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

Singapore’s dependence on Malaysian water was more than an economic inconvenience—it was a knife held permanently at the nation’s throat. Malaysia supplied roughly half of Singapore’s water through agreements that could be renegotiated or, in worst-case scenarios, simply terminated during political disputes. Malaysian politicians occasionally reminded Singapore of this vulnerability during tense moments, and Lee understood that no nation could truly call itself independent while relying on a neighbor’s generosity for something as fundamental as drinking water. The island received plenty of tropical rain, but it had no natural aquifers or lakes to store that water. Every drop that fell either ran directly into the ocean or sat briefly in small reservoirs before being consumed.

Lee approached the water challenge like an engineering problem that could be solved through technology and willpower rather than geography. His government invested heavily in expanding reservoir capacity by damming rivers and converting entire marine inlets into freshwater storage through massive barriers. Marina Reservoir, created by damming the mouth of the Marina Channel, transformed saltwater into one of the island’s largest freshwater sources. Then came the truly ambitious innovations—Singapore developed advanced water reclamation technology that could purify sewage into drinking water so clean it exceeded World Health Organization standards. This recycled water, branded as NEWater to make it psychologically palatable, now provides 40 percent of Singapore’s water needs. Desalination plants were built to convert seawater into fresh water, though the process remained expensive and energy-intensive. By the time Malaysia-Singapore water agreements came up for renegotiation in the 2000s, Singapore could approach the table without desperation. Lee had given his country what seemed impossible for a tropical island with no natural water sources—genuine water security built through technology, planning, and massive infrastructure investment that most nations his size would never attempt.

The Iron Fist Behind the Prosperity

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

Lee Kuan Yew’s Singapore became famous for two contradictory realities that somehow coexisted—extraordinary economic success paired with political controls that made Western democracies deeply uncomfortable. Lee believed that Western-style liberal democracy, with its emphasis on individual rights and free speech, was a luxury that fragile young nations couldn’t afford. He’d watched newly independent countries across Africa and Asia collapse into chaos, military coups, or ethnic violence after trying to implement democratic systems their societies weren’t ready to sustain. His conclusion was blunt and unapologetic—Singapore needed discipline first, prosperity second, and political freedom only after both were secure. Critics called it authoritarianism dressed in efficient suits. Lee called it survival.

The mechanisms of control were sophisticated and multilayered. The Internal Security Act allowed detention without trial for people deemed threats to national security, a power inherited from British colonial rule that Lee expanded and wielded freely against political opponents. Opposition politicians found themselves sued for defamation over criticisms that would be considered normal political discourse in London or Washington. The lawsuits weren’t meant just to win damages but to bankrupt opponents and chill future criticism. Media outlets operated under licensing requirements that made government displeasure financially dangerous. Public protests required police permits that were rarely granted. Even seemingly trivial matters fell under regulation—chewing gum was banned, littering carried hefty fines, and failure to flush public toilets could result in penalties. Lee argued that these restrictions created the stable foundation that allowed everything else to flourish. Foreign investors didn’t worry about strikes shutting down factories. Ethnic tensions didn’t explode into riots. Crime rates dropped to levels that made Singapore one of the world’s safest cities. The bargain was clear even if unspoken—surrender some freedoms, gain security and prosperity. Millions of Singaporeans accepted that trade, though whether out of genuine agreement or pragmatic resignation remained eternally debatable.

Meritocracy Without Mercy

Lee Kuan Yew built Singapore on a principle that sounds fair in theory but feels brutal in practice—meritocracy taken to its absolute extreme. He believed that the best person should always get the job, the promotion, the scholarship, or the government position, regardless of their family background, ethnic identity, or personal connections. This wasn’t just philosophy—it became embedded in every institution from elementary schools to cabinet appointments. Students took standardized exams that determined their entire educational trajectory by age twelve. Civil servants competed for positions through rigorous testing and evaluation systems designed to be immune to favoritism. Even Lee’s own children had to prove themselves through the same gauntlet, though critics noted that having the prime minister as your father probably didn’t hurt networking opportunities.

The system produced spectacular results and deep anxieties in equal measure. Singapore developed a highly capable bureaucracy and professional class that could compete globally. Talented children from poor families could rise to positions that would have been impossible in more traditional Asian societies where family connections dominated. But the flip side was a society that often felt ruthlessly competitive and unforgiving of failure. Students faced immense pressure to perform because falling behind academically meant being tracked into lower-tier schools and vocational paths with limited upward mobility. Parents invested fortunes in tutoring to give their children every possible advantage. The suicide rate among young people became a recurring concern. Lee acknowledged the stress but never apologized for the system. He argued that Singapore’s survival depended on extracting maximum potential from limited human resources. In his view, compassion that protected mediocrity was actually cruelty because it weakened the nation’s ability to compete. Whether that trade-off was worth it remains one of the most contested aspects of his legacy, debated in living rooms and academic papers long after his death.

The Legacy That Outlived the Man

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Michael Stroud/Daily Express/Hulton Archive

Lee Kuan Yew stepped down as prime minister in 1990 after 31 years in power, though he remained influential as senior minister and minister mentor until his death in 2015 at age 91. By the time he left office, Singapore’s transformation was complete and undeniable. The GDP per capita had soared from around $400 at independence to over $12,000, placing it among developed nations. The port had become the world’s busiest. The airport won awards year after year. Literacy rates approached 100 percent. The island that experts predicted would fail had become a case study that development economists still dissect, trying to understand which elements could be replicated elsewhere and which were unique to Singapore’s specific circumstances and Lee’s particular personality.

His legacy remains deeply complicated and stubbornly resistant to simple judgments. Supporters point to tangible results—a poor population lifted into prosperity, racial harmony maintained in a diverse society, infrastructure that works, institutions that function, and a quality of life that draws talent from around the world. Critics counter that success doesn’t justify authoritarian methods, that economic development could have happened with more political freedom, and that Singapore’s model teaches dangerous lessons to dictators who want to justify repression. The truth probably lives somewhere in the uncomfortable middle. Lee proved that visionary leadership combined with ruthless execution could build a modern nation in a single generation, but he also demonstrated how easily development and control can become intertwined until separating them feels impossible. His Singapore works brilliantly by many metrics, yet it also asks citizens to accept limitations on freedom that people in messier democracies would reject. That tension—between efficiency and liberty, between collective good and individual rights—defines Lee’s achievement and ensures that debates about his methods will continue long after the economic miracle he engineered has become historical fact.

FAQs

Yes, he publicly acknowledged forcing Chinese-educated citizens to learn English caused pain, though he never regretted the policy itself. He believed the economic benefits justified the cultural cost.

Through strict housing quotas preventing ethnic enclaves, mandatory bilingual education, and laws criminalizing speech that could incite racial or religious tensions, backed by serious enforcement.

Lee’s approach required incorruptible leadership, long-term political stability, strategic geography, and a small homogeneous population—conditions rarely found together elsewhere in the developing world.

Many faced defamation lawsuits that bankrupted them, some fled the country, and others were detained under security laws. Few opposition figures survived politically during his active years.

Core elements remain—meritocracy, anti-corruption, pragmatic economics—but younger leaders have cautiously loosened some social restrictions while maintaining the fundamental governing framework he established.