Pin

Pin The S1500, shaped like a massive airship, spans roughly the length of a basketball court and rises as high as a 13-storey building / Photo courtesy Handout

Synopsis: China recently tested a revolutionary flying wind turbine that hovers high above the ground, capturing stronger winds unavailable to traditional turbines. These airborne systems use tethered balloons or kites to reach altitudes where wind speeds are consistently higher and more reliable. Several countries including the United States, Germany, and the Netherlands are racing to develop this technology. The floating turbines promise cheaper installation costs, easier deployment in remote areas, and access to powerful high-altitude winds that could transform renewable energy production worldwide.

A massive white airship floated 6,560 feet above Yibin city in China’s Sichuan Province in January 2026, and nobody mistook it for a weather balloon. The S2000 Stratosphere Airborne Wind Energy System was making history as the world’s first megawatt-class flying wind turbine to successfully feed electricity into a power grid. During its test flight, this helium-filled contraption generated 385 kilowatt-hours of electricity—enough to fully charge about 30 electric vehicles.

Beijing Linyi Yunchuan Energy Technology developed this remarkable device in partnership with Tsinghua University and the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The system measures roughly 197 feet long and contains 12 wind turbines arranged in a circular duct beneath a helium-filled envelope. Unlike the scattered experiments of previous years, this test proved that airborne wind energy could move beyond laboratory curiosities into actual commercial operation.

The breakthrough arrives at a critical juncture for renewable energy. China leads the world in carbon emissions but also in renewable energy development, having installed nearly 80 gigawatts of wind capacity in 2024 alone. The S2000 represents China’s bet on a technology that could reach winds conventional turbines can only dream about, all while requiring less land and infrastructure than traditional wind farms.

Table of Contents

The Problem Traditional Turbines Can't Solve

Pin

Pin Traditional Windmill / Photo courtesy Pixabay

Traditional wind turbines face a stubborn ceiling. Engineers have built them taller and heavier over decades, but physics eventually says no. The largest turbines now reach about 300 feet high, requiring massive steel towers anchored in concrete foundations that weigh hundreds of tons. Going taller becomes exponentially expensive and structurally challenging.

The real frustration lies in what’s happening just overhead. At altitudes above 1,500 feet, wind speeds are typically 50 to 100 percent stronger than at ground level. These high-altitude winds blow more consistently too, without the turbulence caused by hills, buildings, and forests. Yet conventional turbines can’t reach them, locked to the ground by their own weight and engineering constraints.

Remote communities face an even thornier problem. Building traditional wind farms in isolated regions means hauling enormous tower sections and turbine components across difficult terrain. Installation requires heavy cranes and extensive infrastructure. Many places with excellent wind resources simply can’t justify the cost and logistical nightmare of conventional turbine construction. The flying wind turbine concept emerged from this very real frustration with ground-based limitations.

How the Chinese System Actually Works

Pin

Pin S2000 Stratosphere Airborne Wind Energy System (SAWES) / Photo courtesy Yanko Design

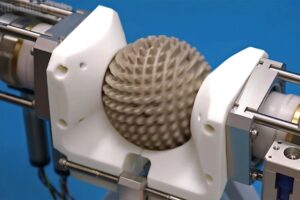

The S2000 operates on a principle that would’ve seemed absurd twenty years ago—letting the turbine float instead of building it higher. A helium-filled aerostat measuring 20,000 cubic meters provides the lift, functioning much like an airship or modern blimp. This envelope supports a ring structure containing 12 lightweight turbines that spin when high-altitude winds pass through them.

The system takes about 30 minutes to ascend to its operating altitude of 6,560 feet. Once positioned, it maintains a stable hover while generating electricity. A specially engineered tether connects the airborne platform to a ground station, serving three crucial functions simultaneously—it anchors the system against wind forces, transmits generated electricity to the grid, and provides communication links for flight control and system monitoring.

Key components include:

- Helium-filled envelope providing buoyancy

- 12 turbine-generator units arranged in circular array

- High-strength conductive tether for power transmission

- Ground station with power conditioning equipment

- Automated flight control systems

The rated capacity reaches 3 megawatts under optimal conditions, though the January test demonstrated grid integration rather than maximum output. Chief designer Dun Tianrui explained that one hour of operation at current output levels could fully charge approximately 30 electric vehicles. The entire system can be transported in standard shipping containers and deployed in just four to five hours with local helium supply.

Why America's Google Gave Up on This Technology

Pin

Pin Makani Power / Photo courtesy Google X Moonshot

Makani Power seemed destined for success when Google acquired the company in 2013 and folded it into their elite Google X “moonshot factory.” The team had developed an elegant solution—a wing-shaped kite with a 26-meter wingspan that flew in loops while generating 600 kilowatts of power. Small turbines mounted on the wing spun as it circled through the sky, with electricity flowing down the tether to ground stations.

The system worked beautifully in tests. Makani successfully demonstrated offshore operation in Norway in 2019, partnering with Royal Dutch Shell to prove the technology could function above ocean waves. The kite took off vertically using onboard rotors, climbed to 1,000 feet, then shifted into elegant figure-eight flight patterns that maximized energy capture. Engineers described it as watching a graceful aerial ballet that happened to generate clean electricity.

Yet in February 2020, Alphabet shut down Makani after 13 years of development. The official statement acknowledged strong technical progress but admitted “the road to commercialization is longer and riskier than hoped.” The weight of the onboard generators proved problematic, maintenance at sea presented unexpected challenges, and the cost calculations never quite penciled out. Makani released all their patents, research data, and even a two-hour documentary to help other companies learn from their efforts. Sometimes even Google’s money can’t solve every problem.

The Boston Company Targeting Alaska's Remote Villages

Pin

Pin Altaeros Energies Wind Turbine / Photo courtesy Altaeros

While Google’s Makani chased utility-scale power, Altaeros Energies took a different approach entirely. The Boston-based startup, founded by MIT graduates in 2010, designed their Buoyant Airborne Turbine specifically for remote communities where conventional power costs a fortune. Their BAT system uses a helium-filled inflatable ring with a wind turbine suspended inside—simpler and more practical than Makani’s flying wing design.

Altaeros deployed their first commercial system in Alaska in 2014 for an 18-month test. Remote Alaskan villages often pay more than four times the U.S. average for electricity because they’re not connected to power grids. Hauling diesel fuel to run generators in these isolated locations creates astronomical costs. The BAT promised power at about 18 cents per kilowatt-hour, roughly half the prevailing cost.

The Alaska test validated several crucial advantages. The BAT could be deployed quickly without massive construction projects. It worked effectively in harsh weather conditions, reeling itself down to the ground during dangerous storms. The higher altitude operation meant critters rarely encountered the spinning blades, and safety lights warned aircraft. Altaeros proved that airborne wind energy could serve niche markets even if it never replaced large wind farms. Their focus on disaster relief zones and military bases opened new possibilities that utility-scale developers had overlooked.

Germany's Kite Approach and Europe's Race

Pin

Pin Skysails power sails a kite that can create energy / Photo courtesy SkySails-Power

Germany entered the airborne wind competition with characteristic engineering thoroughness. SkySails Power developed massive fabric kites—some measuring 320 square meters—that fly at altitudes between 330 and 980 feet. The company initially made its reputation designing kites that pulled cargo ships, reducing fuel consumption by 10 to 35 percent. Applying that expertise to electricity generation seemed like a natural progression.

The German approach uses what engineers call “ground-gen” systems. The kite stays connected to a winch on the ground, and as wind pulls the kite upward, the winch unspools while driving a generator. When the tether reaches its maximum length, the kite depowers and the winch reels it back in using minimal energy. This pumping cycle repeats continuously, with the power-generating phase producing far more energy than the recovery phase consumes.

Berlin-based EnerKite developed a similar concept but with rigid wings instead of fabric kites. Their mono-wing design flies controlled patterns connected to ground stations through bridles and tethers. Meanwhile, companies across the Netherlands and other European nations pursued their own variations. The European efforts typically focused on lower altitudes than the Chinese system, prioritizing easier deployment and faster return on investment. Each national approach reflected different assumptions about which markets would adopt the technology first and what problems needed solving most urgently.

The Physics That Makes High-Altitude Wind So Valuable

Wind speed increases dramatically with altitude, following what meteorologists call the wind gradient or wind shear effect. At ground level, friction from terrain, vegetation, and structures slows wind considerably. As altitude increases, this friction diminishes and wind flows more freely. The mathematical relationship isn’t linear—wind speeds often double or triple between the surface and altitudes of just 1,500 to 2,000 feet.

More importantly, high-altitude winds blow more consistently. Ground-level turbines face a frustrating reality where wind speeds fluctuate wildly throughout the day and across seasons. A turbine might generate full power one hour and sit completely still the next. These winds also flow more smoothly without the turbulent eddies created when air tumbles over hills and around obstacles.

Wind characteristics by altitude:

- Ground level (30-100 feet): Highly variable, disrupted by terrain

- Low altitude (300-500 feet): Moderately consistent, still affected by surface features

- Mid altitude (1,000-2,000 feet): Stronger and steadier winds

- High altitude (2,000+ feet): Fastest and most reliable winds, approaching jet stream characteristics

The energy available in wind increases with the cube of velocity. That mathematical relationship means doubling wind speed provides eight times more power. A turbine operating at 2,000 feet in winds of 30 mph captures dramatically more energy than an identical turbine at 300 feet experiencing 15 mph winds. This fundamental physics explains why engineers have pursued airborne wind concepts despite the obvious engineering challenges.

The Material Science Breakthrough Making It Possible

Building flying wind turbines required solving problems that didn’t exist for conventional turbines. The tether alone presented extraordinary challenges. It needed to conduct electricity efficiently while remaining light enough not to drag the airborne platform earthward. It had to withstand constant tensile loading from high-altitude winds pulling in unpredictable directions. And it required resistance to ultraviolet radiation, temperature cycling, and the abrasive effects of particulate matter in the air.

Modern composite materials made the difference. Carbon fiber reinforced polymers provided strength-to-weight ratios that seemed impossible two decades ago. Engineers developed specialized coatings that resisted UV degradation without adding significant weight. The electrical conductors themselves became lighter through careful alloy selection and hollow cable designs that maximized current-carrying capacity while minimizing mass.

The airship envelope material presented equally demanding requirements. It needed to retain helium for months without significant leakage, remain flexible enough to deploy from shipping containers, withstand temperature extremes from ground level to high altitudes, and resist tears while weighing almost nothing. Companies like Beijing Linyi Yunchuan invested heavily in developing proprietary envelope materials, even building dedicated production facilities. The Chinese team announced plans to reach 800,000 linear meters of annual production capacity by 2028, specifically to reduce dependence on imported materials. Advanced materials technology enabled airborne wind energy more than any single innovation in turbine design itself.

Why Most Airborne Wind Companies Failed

The graveyard of airborne wind energy startups tells an instructive story. Dozens of companies raised millions in funding throughout the 2010s, most disappearing quietly without ever deploying commercial systems. Even well-funded efforts like Makani couldn’t bridge the gap between promising prototypes and profitable products. Understanding these failures reveals why China’s S2000 achievement matters so much.

Many companies underestimated the complexity of autonomous flight control. Making a kite or airship fly steadily at altitude while generating power requires sophisticated software that constantly adjusts to changing wind conditions. Early systems crashed or became uncontrollable during unexpected weather events. Engineers discovered that reliable autonomous operation demanded years of flight testing and software refinement that burned through venture capital faster than revenue could materialize.

Maintenance presented another killer problem. Ground-based turbines already require regular maintenance, but technicians can drive trucks to them and use cranes to replace components. Airborne systems need retrieval and redeployment for every service event, adding enormous costs. Some designs required specialized equipment to capture and dock flying turbines, equipment that itself needed maintenance. The economic calculations that looked promising on spreadsheets collapsed when real-world operational costs emerged. Companies pursuing offshore installations faced even worse challenges, with saltwater corrosion and weather windows for sea-based operations destroying profitability projections. Only the most pragmatic designs focusing on specific niches survived this brutal market selection process.

Where This Technology Could Actually Deploy First

Remote military bases present the most obvious early market for airborne wind turbines. Transporting diesel fuel to forward operating positions costs the U.S. military hundreds of dollars per gallon when factoring in logistics, security convoys, and combat risks. A floating turbine that deploys from a few containers and generates power for months could transform expeditionary operations. The military already pays premium prices for energy solutions that increase operational flexibility, making the cost calculations far more favorable than civilian applications.

Island communities disconnected from mainland power grids represent another promising market. Places like Alaska’s Aleutian chain, remote Pacific islands, and isolated Caribbean communities currently rely on expensive diesel generators. The combination of high electricity costs and strong consistent winds makes these locations ideal for airborne systems. The BAT system from Altaeros specifically targeted this market, recognizing that even modest improvements over diesel generation created enormous value in isolated settings.

Disaster relief operations could benefit immediately from rapidly deployable airborne turbines. When hurricanes, earthquakes, or floods knock out conventional power infrastructure, relief organizations currently truck in diesel generators that consume fuel transported at premium cost. Airborne turbines packed in containers could deploy within hours, providing clean power while traditional infrastructure undergoes repair. Mining operations in remote locations face similar economics—they currently pay extraordinary sums for diesel-generated electricity, making even expensive alternative technologies economically competitive. The technology needs to prove reliable first, but these niche markets don’t require the cost reductions necessary for mainstream grid-scale deployment.

The Regulatory Puzzle Nobody's Solved Yet

Flying wind turbines occupy a regulatory gray zone that makes deployment complex. Aviation authorities classify them as tethered aerostats, which fall under different rules than aircraft. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration permits tethered balloons to fly nearly 2,000 feet high below most flight patterns, but each installation requires specific approval. The turbines must include safety lights and locator beacons while operators must notify air traffic control of their presence and location.

Environmental regulations create another compliance maze. Do airborne turbines require the same environmental impact studies as conventional wind farms? Wildlife agencies want assurances about bird and bat collisions, even though the turbines operate at altitudes where few creatures fly. Some jurisdictions treat them as temporary structures requiring minimal permits, while others demand full environmental reviews. The S2000’s classification as suitable for “urban use” required Beijing Linyi Yunchuan to navigate Chinese regulations that had no precedent for floating power stations.

International airspace regulations compound the complexity. The offshore Makani system operating in Norwegian waters required coordination between multiple regulatory bodies. As companies contemplate deploying turbines over international waters to capture ocean winds, the legal framework remains largely undefined. Who has jurisdiction over a turbine floating above the high seas? What happens when tethers break and turbines drift across national boundaries? Insurance companies struggle to price policies for risks they can’t adequately assess. Until regulatory frameworks catch up with the technology, deployment will remain constrained by bureaucratic uncertainty rather than engineering limitations alone.

What Success Would Actually Look Like by 2035

Realistic projections suggest airborne wind energy will remain a niche player rather than replacing conventional turbines wholesale. Industry analysts estimate that by 2035, airborne systems might achieve 40 percent lower costs than current prototypes, making them competitive in specific markets. This would enable several thousand installations serving remote communities, military bases, and industrial operations rather than millions of turbines feeding major grids.

China’s rapid commercialization timeline offers the most aggressive scenario. Beijing Linyi Yunchuan has already begun small-batch production of the S2000 and signed letters of intent with coastal cities and high-altitude regions. If their production facility in Zhoushan reaches planned capacity and reliability proves acceptable, China could deploy hundreds of systems by 2030. This would make airborne wind a meaningful contributor to China’s renewable energy portfolio, particularly in regions where conventional turbines face geographic constraints.

The technology’s most transformative impact might occur in developing nations lacking extensive electrical infrastructure. Countries across Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America could leapfrog directly to airborne systems rather than building conventional wind farms that require extensive grid connections. Imagine Nigeria deploying floating turbines to power rural villages that never had reliable electricity. The systems’ rapid deployment capability and container-based transport align perfectly with developing world constraints. Success won’t mean airborne turbines powering Manhattan or London—it means providing affordable clean energy to the three billion people who currently lack reliable electricity. That would represent a genuine revolution, even if high-altitude winds never dominate the renewable energy landscape in wealthy nations with mature electrical grids.

FAQs

Most systems can reel themselves down to the ground when dangerous weather approaches. The S2000 can be deflated and stored in containers within hours, while the BAT system automatically descends during storms. However, unexpected severe weather remains a reliability concern.

Collision risks appear minimal because most birds and bats don’t fly above 1,500 feet. The turbines operate well above typical wildlife flight altitudes. Safety lights also warn away any high-altitude migrants. Research continues to monitor actual wildlife impacts.

Current prototypes target several months of continuous operation. The S2000 design allows for controlled descent and re-deployment, with the helium envelope designed for repeated cycles. Long-term durability data remains limited as the technology is so new.

Systems include redundant safety tethers and emergency descent protocols. If the main tether fails, backup tethers and controlled deflation systems should prevent uncontrolled drift. Regulatory requirements mandate multiple failsafe mechanisms to prevent dangerous scenarios.

Not yet for grid-scale applications, but costs are declining rapidly. In remote locations where diesel generators currently dominate, airborne turbines already compete economically. Mass production and improved designs should reduce costs by 40% by 2035, expanding viable markets.