Pin

Pin Photo by NASA

When we stroll through a supermarket, the colorful fruit section might seem like the whole world in a basket. Apples, bananas, mangoes—familiar, reliable, and tasty. But the truth is, every fruit on planet Earth isn’t on that shelf. There are fruits that grow wild on cliffsides, in tribal backyards, and on windswept islands you’ve never heard of.

In the dense forests of Meghalaya, locals pluck soh-lyngngoh, a tiny fruit that tingles like electricity on the tongue. Just a few thousand kilometers away in South America, the jabuticaba grows directly on tree trunks, looking like a grape but tasting like something out of a dream. These fruits are rarely exported. They’re not on Instagram. But they’re deeply loved where they grow.

The world still hides secrets. And fruits—bright, pulpy, strange, and sacred—are one of the most overlooked clues to how diverse and delicious life really is.

Table of Contents

Rambután

Pin

Pin Image by Engin Akyurt from Pixabay

Rambután might look like something from outer space, but it’s a beloved tropical fruit across Southeast Asia. Covered in soft, hair-like spines, its name comes from the Malay word rambut, meaning “hair.” Beneath that quirky red shell lies a translucent, grape-like flesh that’s sweet, juicy, and lightly floral.

Locals often enjoy rambutan fresh, chilled, or even canned in syrup. It’s commonly sold by the roadside in countries like Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines, where farmers bunch them up in vibrant, spiky clusters. The fruit is best eaten freshly picked, when its sugars are at their peak and the texture is at its most tender.

What makes rambutan special isn’t just its taste—it’s how it connects people. Families share it during summer, children play with its empty shells, and street vendors call out prices in markets buzzing with heat. It’s a fruit that feels like home in the tropics and a surprise in every bite for the rest of us.

Jabuticaba

Pin

Pin Image by heloenniareis from Pixabay

At first glance, the jabuticaba tree might look like it’s covered in giant black pearls. But these glossy orbs aren’t ornaments—they’re fruits growing directly from the trunk. Native to Brazil, jabuticaba is one of the most visually striking fruits on Earth, and its tree looks like something out of a fairy tale.

The fruit resembles a grape but with thicker skin and a tangier flavor. Inside, it holds a soft, juicy pulp that bursts with a mix of plum, lychee, and subtle spice. Locals often eat it fresh off the bark or use it in jellies, wines, and even liqueurs. It’s not easily exported because it spoils quickly, making it a true delicacy of the region.

For Brazilians, the jabuticaba isn’t just a snack—it’s part of memory and tradition. Grandparents tell stories under its shade. Kids climb the tree to eat the fruit straight from the bark. It’s proof that nature still has tricks up its sleeve, hidden in places only locals truly know.

Buddha’s Hand

Pin

Pin Burkhard Mücke, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Buddha’s Hand isn’t your typical citrus. Shaped like a hand with outstretched fingers, this lemon-like fruit is as spiritual as it is strange. In parts of China, India, and Japan, it’s often placed on altars as an offering. Its unusual shape, resembling fingers in a gesture of blessing, is believed to bring good fortune and happiness.

Unlike most citrus fruits, Buddha’s Hand has no juice or pulp. Instead, it’s all rind—fragrant, floral, and intensely aromatic. Chefs love to zest it over salads, infuse it into syrups, or candy it into tangy-sweet treats. Even a small shaving can fill an entire kitchen with a clean, lemony scent that feels both fresh and sacred.

But beyond food, it plays a role in culture. It’s gifted on special occasions, carried for luck, and admired for its beauty. Touching its curled yellow “fingers” feels like shaking hands with something ancient. Buddha’s Hand reminds us that fruit isn’t just for eating—it’s a connection between earth, spirit, and story.

Salak

Pin

Pin Image by Robert Lens from Pixabay

Salak, often called snake fruit, earns its name from its reddish-brown, scaly skin that looks remarkably like snakeskin. Native to Indonesia and parts of Southeast Asia, it might seem intimidating at first glance. But peel back that tough exterior, and you’ll find crisp, juicy segments with a flavor that dances between apple, banana, and honey.

The texture of salak is part of its charm—firm and crunchy with a mild astringency that gives way to mellow sweetness. Some varieties lean tart, while others are sugary and fragrant. Locals enjoy it as a snack, often dipping it in chili-salt for a spicy-sour twist. It’s also used in salads and pickled in brine for a tangy preserve.

Sold in heaps at local markets, salak is a symbol of resilience and surprise. It teaches us not to judge fruit by its skin. What looks armored and harsh on the outside holds a gentle sweetness within. Nature, as always, knows how to protect its treasures with flair.

Mangosteen

Pin

Pin Image by taboty from Pixabay

Beneath its thick, deep purple rind lies one of the softest, most delicate fruits you’ll ever taste. Mangosteen, often called the “queen of fruits,” is revered across Southeast Asia not just for its flavor, but for the quiet elegance of its design. Crack it open gently, and you’ll find snowy white segments that melt on the tongue.

The taste is a perfect balance—sweet like a peach, slightly tart like a pineapple, with a floral note that lingers. Mangosteen isn’t just eaten for pleasure; it’s wrapped in tradition. In Thailand, it’s offered to guests as a sign of hospitality. In Ayurveda and traditional medicine, it’s praised for its cooling properties and antioxidant-rich rind.

But mangosteen is sensitive. It doesn’t travel well, which is why many around the world have never tasted it fresh. That moment of breaking open the thick shell and finding soft white jewels inside feels almost sacred. It’s a reminder that some fruits are meant to be savored, not shipped.

Noni

Pin

Pin ZSM, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Noni is not a fruit you eat for flavor. With its lumpy green skin and sharp, cheese-like smell, it’s often called “vomit fruit” by the uninitiated. But in Polynesian culture and across parts of South Asia, this unusual fruit is respected—almost revered—as a powerful medicinal ally.

Packed with nutrients, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory compounds, noni is consumed as juice, dried, or fermented. It’s believed to support immunity, digestion, and even mental clarity. In many island communities, elders still prepare noni tonics from memory, using it to treat wounds, skin infections, and fatigue. The knowledge is passed down like a sacred ritual.

What makes noni fascinating isn’t just its medicinal power—it’s the dedication with which people endure its taste for the sake of healing. It’s a fruit that reminds us that nature often hides its deepest gifts behind layers of discomfort. And those willing to respect that relationship are often rewarded with vitality that can’t be bottled in modern pills.

Chérimoya

Pin

Pin Image from Instagram

Mark Twain once called chérimoya “the most delicious fruit known to men,” and it’s not hard to see why. Native to the Andean valleys of South America, this heart-shaped fruit has a pale green, scaly skin and a soft, creamy flesh inside that tastes like a blend of banana, pineapple, and vanilla.

Locals sometimes refer to it as the “ice cream fruit”—not just for its flavor, but for the way it melts on your tongue. Each spoonful is a dreamy, custard-like bite that needs no sugar or spice. Often eaten chilled, chérimoya is a summertime luxury in countries like Peru, Ecuador, and Bolivia, where it’s sold at markets like a rare jewel.

But it’s more than dessert. In traditional cultures, chérimoya is used to calm nerves and improve mood, almost like a natural stress reliever. There’s something gentle and soothing about its texture and taste—like the fruit itself is trying to lull you into peace. It’s nature’s softest whisper, offered in green.

Bael

Pin

Pin Image by Rajesh Balouria from Pixabay

Bael fruit doesn’t beg for attention. Its round, woody shell is so hard it needs a firm strike to crack open. But inside, the golden pulp is sweet, sticky, and deeply aromatic—a summer staple across India, Sri Lanka, and parts of Southeast Asia. It’s often blended into juice, chilled with a bit of jaggery, and served to cool down scorching afternoons.

In Hindu tradition, the bael tree is sacred—its leaves are offered in prayers to Lord Shiva, and its fruit is believed to purify the body and mind. Ayurvedic medicine holds bael in high regard for its digestive benefits, especially for soothing the gut during hot months. It’s the kind of fruit that doesn’t just quench thirst—it settles the soul.

There’s a timeless rhythm to bael season. Vendors slice open the shell with a practiced hand, temple courtyards fill with its scent, and elders sip the nectar slowly, like a ritual. It’s a fruit that’s more than nourishment—it’s memory, medicine, and quiet reverence.

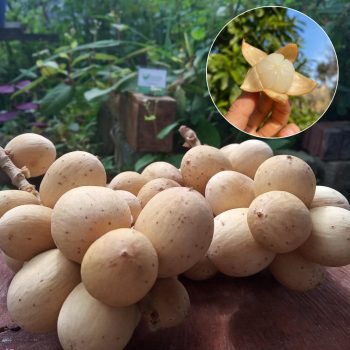

Langsat

Pin

Pin Image from Instagram

Langsat is easy to overlook. It looks like a small, dusty potato at first glance. But peel back its thin, beige skin, and you’ll uncover pearly white segments that glisten like morning dew. Native to Malaysia and Indonesia, langsat is a hidden gem among tropical fruits, beloved by those who know its taste and rhythm.

The flavor is a graceful dance between sweet and tart, often compared to grapefruit crossed with grapes—delicate, juicy, and refreshing. Locals enjoy it by the handful during harvest season, often gathered in bunches that resemble miniature golden grapes. In village homes, it’s common to see bowls of langsat sitting on wooden tables, the peels curling beside afternoon cups of tea.

What’s charming about langsat is its quiet humility. It doesn’t have flashy colors or bold aromas, but it offers an honest taste that speaks to the warmth of the places it grows. It’s the kind of fruit that stays with you—not because it shouts, but because it lingers gently in memory.

Miracle Fruit

Pin

Pin Hamale Lyman, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The miracle fruit lives up to its name—not with bold flavor, but with a superpower hidden in its skin. Native to West Africa, this small red berry doesn’t taste like much on its own. But after eating one, your entire taste world flips. Sour things—like lemons or vinegar—suddenly taste sugary sweet for up to an hour.

This transformation happens thanks to a protein called miraculin. It temporarily binds to your taste buds, altering how they respond to acidity. Locals have long used miracle fruit to sweeten bland or sour foods naturally, especially during food shortages. Today, it’s also used in “flavor-tripping” parties, where people sample tangy foods just to marvel at the change.

But deeper than the novelty, miracle fruit teaches a quiet lesson: perception is fluid. What tastes harsh can suddenly become soft. What was once unpalatable might become a pleasure. It’s a reminder—delivered through a simple berry—that the way we experience the world can shift with just one small, unexpected change.

FAQs

Yes, all the fruits listed are safe when properly prepared. Some, like ackee or noni, must be eaten ripe or cooked correctly to avoid health issues.

Local markets in tropical regions are your best bet. Specialty stores or online sellers sometimes offer imported or dried versions too.

Many spoil quickly, are fragile to ship, or grow in limited regions. That’s why they often stay close to home—enjoyed best where they’re born.

Absolutely! Many are rich in antioxidants, vitamins, and medicinal properties, used traditionally for healing and boosting wellness.

Taste is personal! But mangosteen, chérimoya, and rambutan are often favorites for their sweetness and soft, luxurious textures.