Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Globe Makers

Synopsis: The Silk Road was never romantic. It was a harsh reality where survival meant everything and profit justified risk. For over fifteen hundred years, this network of trade routes connected Asia to Europe through some of Earth’s most unforgiving terrain. Merchants died of thirst in deserts. Bandits murdered entire caravans. Cities that grew wealthy one generation turned to ruins the next. Yet the routes persisted because kingdoms needed what lay beyond their borders. This is the real story—one of human endurance, desperation, and the cold economics that shaped civilizations.

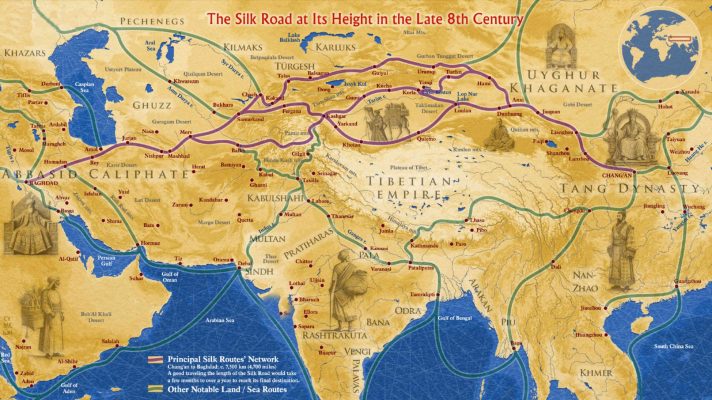

What is the Silk Road? It was a web of overland and maritime routes connecting China to the Mediterranean, operating roughly from 130 BCE to 1453 CE. The name itself only appeared in the 19th century, coined by a German geographer. Ancient travelers never called it that—they simply knew these paths as the only way to move goods between distant lands.

The routes existed because geography left no choice. Kingdoms separated by mountain ranges and deserts needed each other’s resources to survive and prosper. Chinese silk became currency in Roman markets. Persian silver flowed eastward. Indian spices commanded prices higher than gold in European cities. No single empire controlled the entire network, which meant every border crossing involved negotiation, bribery, or bloodshed.

Merchants rarely traveled the full distance themselves. Goods changed hands dozens of times between origin and destination, each middleman taking his cut. A bolt of silk leaving Chang’an might pass through ten different kingdoms before reaching Constantinople. This system meant information traveled slowly and inaccurately. Romans believed silk grew on trees because they’d never met anyone who’d actually seen a silkworm. Distance bred mystery, and mystery inflated prices—a truth merchants exploited ruthlessly.

Table of Contents

The Geography That Shaped Everything

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of World History Encyclopedia

The routes existed because the land itself dictated where humans could survive. The northern path skirted the Taklamakan Desert’s edge, where summer temperatures reached levels that killed unprepared travelers within hours. Caravans moved at night during hot months, navigating by stars while the sand still held some coolness. Towns sprouted wherever natural springs broke through the desert floor, and these oasis settlements became chokepoints where local rulers extracted heavy taxes from passing merchants.

Southern routes crossed the Pamir Mountains, where altitude sickness claimed lives and narrow passes turned into death traps during avalanches. Pack animals stumbled on icy trails, sending entire loads of precious cargo tumbling into gorges thousands of feet deep. Winter closed these passes completely for months, stranding anyone foolish enough to miscalculate their timing. Yet merchants still chose these paths because they connected directly to Indian markets, cutting out Persian middlemen who controlled the easier western approaches.

The maritime routes offered different dangers but no less deadly ones. Monsoon winds powered ships across the Indian Ocean, but only during specific seasons. Miscalculate the timing and your vessel sat becalmed for months, supplies dwindling while the crew grew mutinous. Pirates operated from hidden coves along the Malacca Strait, attacking merchant vessels that couldn’t outrun their smaller, faster boats. Storms sent ships to the ocean floor with no survivors to tell the tale. The sea routes moved more cargo than camel caravans ever could, but the stakes rose proportionally with each voyage.

The Cargo That Justified the Risk

Pin

Pin Photo by Howdy Hada

Silk dominated the luxury trade, but calling these routes by that name oversimplifies what actually moved along them. Chinese silk reached Roman senators who paid its weight in gold, literally. The fabric’s production remained a guarded state secret for centuries—revealing the process meant execution. This monopoly allowed Chinese dynasties to control prices and manipulate foreign kingdoms through supply restrictions. When Byzantine monks finally smuggled silkworm eggs out of China in hollow bamboo canes around 550 CE, it broke an economic stranglehold that had lasted nearly seven hundred years.

Spices moved westward in quantities that seem absurd until you understand medieval preservation needs. Without refrigeration, meat spoiled quickly and tasted worse. Black pepper, cinnamon, and cloves masked the flavor of decay and made stored food palatable through long winters. These weren’t luxuries for the wealthy alone—they were survival goods that entire populations depended on. A single ship’s cargo of pepper could make a merchant wealthier than minor nobility. Wars were fought over access to the Spice Islands, and kingdoms rose or fell based on their ability to control these trade flows.

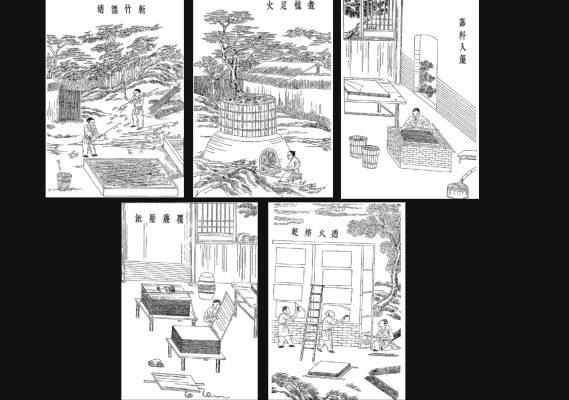

But the most valuable cargo was often the smallest. Lapis lazuli from Afghan mines became the blue pigment in European religious paintings. Chinese papermaking technology reached the Islamic world after the Battle of Talas in 751 CE, when captured Chinese soldiers revealed the process to their captors. Glass moved east while porcelain traveled west. Each item represented knowledge as much as material—techniques that could transform entire economies once transplanted to new soil. The roads carried ideas wrapped in commerce, and those ideas often proved more dangerous to existing power structures than any army.

Cities Built on Crossroads and Greed

Pin

Pin Samarkand, Samarqand Region, Uzbekistan / Photo courtesy of Ehsan Haque

Samarkand grew rich because geography gave it no choice but to matter. The city sat where multiple routes converged, making it unavoidable for caravans heading in any direction. By the 6th century, it had become one of Central Asia’s largest urban centers, its markets filled with merchants speaking dozens of languages. Persians, Indians, Chinese, and Greeks conducted business in caravanserais—fortified inns where traders could sleep behind walls thick enough to stop arrows. The city’s rulers taxed everything that moved through their gates, accumulating wealth that funded palaces, mosques, and armies strong enough to discourage interference from neighboring powers.

Kashgar operated on similar principles at the western edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Every caravan that survived crossing that wasteland needed supplies, fresh animals, and rest before attempting the mountain passes ahead. The city’s bazaars became legendary for their diversity—you could buy goods from three continents within a single afternoon of walking. Local merchants acted as bankers, holding deposits for traders who didn’t want to carry heavy coin across dangerous territory. This financial system worked on reputation alone, since no authority existed to enforce contracts between men from different empires who might never meet again.

But prosperity made these cities targets. Armies swept through repeatedly over the centuries, each conqueror demanding tribute or simply taking what they wanted. Samarkand changed hands between empires so many times that its population learned to treat political authority as temporary. Buildings were constructed to be rebuilt—merchants understood that today’s palace might become tomorrow’s rubble. The Mongol invasions of the 13th century devastated many Silk Road cities so thoroughly that some never recovered their former importance. Wealth concentrated in urban centers created vulnerability, and the same trade that built these places also painted targets on them for every ambitious warlord within striking distance.

Faiths That Traveled Further Than Armies

Pin

Pin Expansion of Buddhism / Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

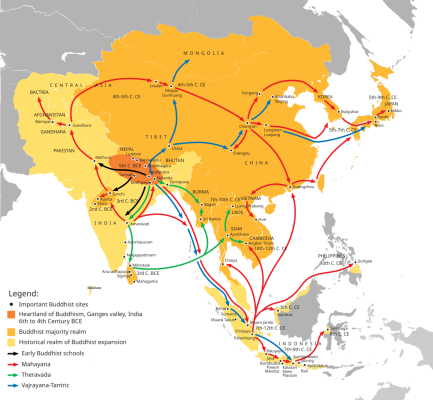

Buddhism moved along the Silk Road more effectively than any military campaign could have achieved. Indian monks carried their teachings into Central Asia and eventually into China, establishing monasteries at every major stop along the northern routes. These weren’t just places of worship—they functioned as schools, hospitals, and banks. Merchants deposited money at one monastery and collected it at another thousands of miles away, trusting the Buddhist network more than any government institution. The religion spread because it solved practical problems for traders who needed trustworthy partners across vast distances. By the 8th century, Buddhist cave temples dotted the entire length of the routes, some carved into cliff faces so remote that modern archaeologists still discover new ones.

Christianity’s Nestorian branch spread eastward through Persia and into China by the 7th century, though it never achieved Buddhism’s dominance. Nestorian merchants established communities in trading cities, building churches that blended architectural styles from multiple cultures. These communities survived for centuries in places like Samarkand and Xi’an, maintaining their faith while adapting to local customs. However, their foreign origins made them vulnerable during periods of xenophobia. Chinese emperors periodically expelled foreign religions when internal problems needed scapegoats, and Nestorian communities disappeared from many cities during these purges, leaving only stone crosses and Syriac inscriptions as evidence they’d existed at all.

Islam’s expansion in the 7th and 8th centuries transformed the Silk Road’s central section entirely. Muslim merchants came to dominate the trade between China and Europe, establishing networks based on shared religious law that standardized contracts across different kingdoms. Islamic scholars traveled with caravans, spreading not just religious texts but also advances in mathematics, astronomy, and medicine. The Arabic numeral system reached Europe through these routes, revolutionizing commerce and science. Yet religious diversity along the roads also meant conflict—competing faiths sometimes led to violence, and rulers who favored one religion over others could destroy centuries of commercial relationships overnight. Faith moved goods efficiently until it didn’t, and then it burned the very roads it had helped build.

Knowledge That Crossed Borders and Changed Civilizations

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Papermaking technology left China through violence, not voluntary exchange. After the Battle of Talas in 751 CE, Arab forces captured Chinese soldiers who knew the papermaking process. Under interrogation or perhaps seeking better treatment, these prisoners revealed techniques that had been state secrets for centuries. Within decades, paper mills operated across the Islamic world, and by the 12th century, the technology reached Europe through Moorish Spain. This single transfer of knowledge transformed literacy, government record-keeping, and eventually sparked the printing revolution. Before paper, European monks spent months copying single books onto expensive parchment made from animal skins. After paper arrived, books became affordable enough that ideas could spread beyond monastery walls and royal courts.

Medical knowledge flowed in multiple directions, though scholars often failed to credit their sources properly. Chinese acupuncture techniques reached Persia, where doctors incorporated them into existing practices. Greek medical texts translated into Arabic preserved knowledge that Europe had lost during its dark ages. When these texts eventually returned to Europe through Spain and Sicily, they came back in Arabic translation, sometimes carrying additional commentary from Islamic physicians who’d advanced beyond the original Greek theories. The concept of the hospital as we understand it today—a place where strangers receive medical care regardless of ability to pay—developed in Islamic cities along the Silk Road and later influenced European medical institutions. Disease also traveled these routes, though that knowledge came at terrible cost. The Black Death likely originated in Central Asia before merchant ships carried infected rats to Mediterranean ports in 1347, killing perhaps half of Europe’s population within five years.

Gunpowder followed a path from Chinese alchemists to Islamic engineers to European cannons, though each culture adapted the technology to their own military needs. Chinese forces used gunpowder primarily for rockets and bombs that terrified enemies psychologically. Islamic armies developed better formulations that burned hotter and more reliably. Europeans eventually perfected the cannon, a weapon that rendered medieval castle walls obsolete and shifted the balance of power toward nations that could afford large artillery parks. By the 15th century, Ottoman cannons breached Constantinople’s walls, ending the Byzantine Empire and effectively closing the land routes that had functioned for over a millennium. Technology that had traveled the Silk Road helped destroy the network that had carried it, a final bitter irony in the routes’ long history.

Empires That Bled Themselves Trying to Own the Routes

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Horizon Dwellers

The Han Dynasty understood that controlling the Silk Road’s eastern terminus meant controlling China’s security. Nomadic tribes from the northern steppes raided Chinese settlements with impunity until Emperor Wu sent armies westward in 138 BCE to establish control over the Hexi Corridor, a narrow strip of land between mountains and desert. This campaign lasted decades and drained the imperial treasury. Thousands of soldiers died garrisoning remote outposts where water had to be hauled in and food supplies arrived months late if they arrived at all. The Han built watchtowers every few miles along vulnerable sections, each manned by troops who knew they’d likely die far from home. But this investment paid off strategically, because it allowed Chinese merchants to trade directly with Central Asian kingdoms instead of dealing with hostile intermediaries who charged ruinous fees or simply murdered caravans and took everything.

The Sassanid Persian Empire positioned itself as the unavoidable middleman between East and West, and for centuries this strategy generated immense wealth. Persian merchants bought Chinese silk and Indian spices, then sold them to Romans and later Byzantines at markups of three hundred percent or more. The Sassanid rulers understood that maintaining this monopoly required military force to keep alternate routes closed. They fought wars against nomadic tribes who tried to open northern passages that would bypass Persian territory entirely. When the Byzantine Empire attempted to establish direct trade relations with China by sending envoys through the Caucasus, Persian armies blocked the route and killed the ambassadors. This aggressive protection of commercial interests worked until it didn’t—the Arab conquests of the 7th century swept away the Sassanid Empire entirely, replacing one set of middlemen with another. All that blood and treasure spent defending trade routes couldn’t save them when a new power arose with better organization and religious motivation that unified previously fractured tribes.

The Mongol Empire took a different approach by making the entire route safer than it had ever been before or would be again. Under Mongol control in the 13th and 14th centuries, a merchant could travel from the Black Sea to Beijing with minimal risk of banditry because Mongol law punished attacks on traders with immediate execution of everyone in the nearest village. This brutal enforcement created what historians call the Pax Mongolica—a peace maintained through terror but effective nonetheless. Trade volumes increased dramatically because merchants no longer needed to hire large armed escorts or factor probable losses into their pricing. Marco Polo’s journey to China became possible only because Mongol control had turned previously impassable regions into something resembling safe passage. But this system collapsed quickly after the Mongol Empire fragmented into competing khanates that fought each other as viciously as they’d once conquered others. Within two generations of Genghis Khan’s death, the routes had become dangerous again, and trade volumes dropped to pre-Mongol levels. Empire had temporarily solved the Silk Road’s security problem, but empires don’t last, and neither did the solution they’d imposed through force.

The Merchants Who Lived Between Worlds

The traders who survived long enough to grow wealthy were a specific breed of men who’d learned to shed fixed identities like snakes shed skin. A successful Silk Road merchant spoke four or five languages badly rather than one perfectly, because miscommunication could be fixed but silence meant no deal at all. They dressed in whatever style the current region demanded, carrying multiple sets of clothing to change at borders. Religious flexibility mattered more than piety—a merchant might pray in a Buddhist temple one month and a mosque the next, not from genuine conversion but because local authorities granted better terms to those who showed respect for their faith. These men existed in the gaps between civilizations, belonging fully to none of them. Their children often grew up speaking languages their fathers barely understood, raised in distant cities while their fathers spent years on the road. Family became an abstraction measured in letters that took months to arrive and might never reach their destination at all.

Caravan leaders held authority that rivaled minor nobility, though their power lasted only as long as the journey did. These men knew which wells still held water and which had gone dry since last season. They understood tribal politics well enough to know which groups could be bribed and which would kill you regardless of what you offered. A good caravan leader kept his merchants alive and his animals healthy, navigating not just terrain but the complicated web of allegiances and enmities that shifted constantly across Central Asia. They hired guards from local tribes when entering their territory, paying protection money that was really just organized extortion made respectable through negotiation. The guards often knew the bandits personally—sometimes they were the bandits during lean seasons. This entire system operated on unwritten rules that outsiders couldn’t learn from books, only through years of experience that killed those who learned too slowly.

The lowest members of caravan society were the laborers who walked beside pack animals for months without pay beyond food and minimal shelter. These men had nothing to lose, having fled debts or crimes in their home regions. They hoped to reach a distant city where they could start fresh, working off their passage by loading and unloading goods, tending animals, and standing watch at night. Many died along the way from disease, exposure, or simple exhaustion. No one recorded their names or mourned their passing beyond the immediate inconvenience of having one fewer hand to do the work. Their bodies were left beside the trail, bones eventually scattered by wind and scavenged by animals. The Silk Road’s prosperity was built on their anonymous suffering, and history remembers the merchants who got rich while forgetting the countless laborers whose deaths made that wealth possible.

When Civilizations Collided and Created Something New

The cities where trade routes intersected became laboratories of cultural fusion that had no equivalent in the isolated kingdoms on either end. A single marketplace in Bukhara or Merv might contain Persian carpet sellers next to Chinese jade merchants, Indian incense dealers beside Byzantine gold traders. These weren’t just economic transactions—they were moments where people who’d never encountered each other’s existence suddenly had to find common ground. Hand gestures evolved into shared trading languages. Mathematical symbols from India merged with Greek geometric concepts, creating new systems that neither culture had developed independently. Musical instruments traveled between regions and transformed as local craftsmen adapted designs to their available materials and aesthetic preferences. The Persian lute traveled east and became the Chinese pipa, then moved to Japan as the biwa, each version reflecting local tastes while maintaining enough similarity that a musician could recognize the shared ancestry.

Artistic styles blended in ways that disturbed cultural purists but produced remarkable innovations. Buddhist statues carved in Gandhara region showed clear Greek influence in their facial features and draped clothing, because Alexander’s conquest centuries earlier had left Greek artisans who’d settled and intermarried with local populations. Their descendants created a hybrid art form that looked foreign to both Greeks and Indians while belonging fully to neither tradition. Chinese paintings began incorporating Persian perspective techniques in the Tang Dynasty, adding depth to compositions that had previously emphasized flat planes and vertical arrangements. These weren’t conscious decisions by individual artists trying to be revolutionary—they were natural results of exposure to foreign techniques that solved problems artists hadn’t known they had. A Persian miniaturist seeing Chinese brush painting might spend years trying to replicate that fluidity, eventually creating something that was neither purely Persian nor Chinese but uniquely his own synthesis.

Food transformed perhaps more thoroughly than any other cultural element because eating was necessary daily activity that brought people together regardless of language barriers. Noodles may have originated in China but traveled west where they became pasta in Italy, though historians still argue about the exact transmission route and timing. Central Asian pilaf rice dishes incorporated Indian spices, Persian cooking techniques, and Chinese vegetables into something that hadn’t existed in any of those cuisines separately. Tea drinking spread from China through Central Asia and eventually reached Europe, but each culture along the route adapted it differently—Tibetans added yak butter, Persians preferred it with sugar and rose water, while the British eventually built an entire social ritual around afternoon tea service. These weren’t cases of one culture imposing its preferences on others through force. They were organic adaptations that occurred because travelers got hungry far from home and local cooks did their best with unfamiliar ingredients, sometimes creating dishes that became more popular than the originals they’d attempted to copy.

The Sea Routes That Drowned the Land

The maritime alternatives had always existed, but improvements in ship construction and navigation during the 15th century made ocean travel decisively more efficient than overland caravans. A merchant ship could carry cargo equivalent to a thousand camels, and while sea voyages carried their own dangers, the cost per unit of goods dropped so dramatically that land routes couldn’t compete on economics alone. Chinese treasure fleets under Admiral Zheng He demonstrated this advantage in the early 1400s, with vessels carrying hundreds of tons reaching as far as East Africa. European powers watched these developments and recognized that whoever controlled sea lanes could bypass the Muslim middlemen who’d dominated Silk Road commerce for centuries. The Portuguese rounded Africa’s Cape of Good Hope in 1488, opening a direct maritime route to India that cut travel time in half compared to overland alternatives. Within decades, Lisbon became a major spice market while traditional Silk Road cities like Tabriz saw their merchant populations dwindle as traders moved to coastal ports where the real money now flowed.

The Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453 gets blamed for closing the Silk Road, but this oversimplifies a more complex economic shift that was already underway. The Ottomans did impose higher tariffs on goods passing through their territory, making overland trade more expensive for European merchants. However, even without Ottoman interference, the sea routes would have eventually won because the basic mathematics of shipping costs favored vessels over pack animals. A camel could carry perhaps four hundred pounds and needed food, water, and rest every day. A ship required wind, which was free, and could sail for weeks without stopping. The Ottoman tariffs accelerated a transition that was inevitable once European navigators learned to reliably cross open oceans. The land routes didn’t vanish immediately—local and regional trade continued for centuries—but the great transcontinental commerce that had defined the Silk Road for over a millennium shifted permanently to maritime channels.

Political fragmentation across Central Asia removed the last advantages that land routes had once offered. When the Mongol Empire provided unified control, a merchant could obtain a single travel permit that was honored from one end of Asia to the other. After the empire collapsed, that same journey required negotiating with dozens of different kingdoms, each demanding separate payments and operating under different legal systems. This bureaucratic nightmare added weeks or months to travel time while significantly increasing costs. Meanwhile, a ship sailing from Venice to India dealt with perhaps three or four major political jurisdictions at most. The ocean didn’t have borders that changed based on which local warlord had won last month’s battle. Maritime routes offered predictability that land routes could no longer guarantee, and in commerce, predictability often matters more than raw speed. Merchants chose the boring reliability of sea lanes over the chaotic adventure of crossing Central Asia, and an entire economic system built over fifteen centuries slowly starved from lack of traffic that had moved on to safer, cheaper alternatives.

The Legacy Written in Routes We Still Follow

The physical roads themselves mostly disappeared under centuries of sand and soil, but the connections they established never fully broke. Modern highways across Central Asia often follow the same mountain passes and desert routes that ancient caravans used, because geography hasn’t changed—those remain the only practical paths through terrain that kills travelers who choose poorly. The Karakoram Highway connecting Pakistan and China runs through valleys where Buddhist monks once walked, and truck drivers today face the same altitude sickness and avalanche dangers that claimed medieval merchants. Even railways built in the 19th and 20th centuries trace paths determined by water sources and mountain gaps that traders identified through trial and error over millennia. We’re still using their geographic knowledge, though modern travelers rarely recognize they’re following routes mapped by anonymous merchants who died a thousand years ago.

The geopolitical concept of Eurasia as a connected space rather than separate continents began with these trade networks. European powers in the 19th century obsessed over controlling Central Asian territory precisely because Silk Road history had taught them that whoever controlled these lands controlled commerce between East and West. The “Great Game” between Russia and Britain involved both empires maneuvering for position across the same regions where Tang Dynasty and Persian armies had fought for identical strategic reasons a millennium earlier. China’s modern Belt and Road Initiative explicitly references Silk Road heritage in its name and follows similar geographic logic—building infrastructure across Central Asia to facilitate trade with Europe while establishing Chinese influence in regions that historically served as buffers between major powers. The ancient routes shaped how modern nations think about trade, security, and regional influence in ways that persist even though the original caravan traffic ended five centuries ago.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy exists in how we think about cultural exchange and globalization itself. The Silk Road proved that isolated civilizations stagnate while connected ones innovate through contact with foreign ideas. Every major technological and artistic advance in human history occurred in regions where different cultures intersected and borrowed from each other, often without acknowledging the debt. Modern opponents of globalization often romanticize a past where cultures remained pure and unchanged, but the Silk Road demonstrates that no such past ever existed. Humans have always traded, traveled, and stolen ideas from each other whenever possible. The routes formalized this process and showed that prosperity follows connection while isolation breeds weakness. That lesson remains relevant today as nations debate how much to engage with global trade networks versus retreating into economic nationalism. The Silk Road’s history suggests that withdrawal comes at a cost measured not just in immediate economic terms but in the slower death of innovation that occurs when societies stop learning from outsiders who see problems differently.

FAQs

Historians debate this endlessly. His account contains accurate details about places he claimed to visit, but also suspicious omissions like never mentioning the Great Wall. He likely traveled parts of it but may have exaggerated or borrowed stories from other merchants to make his book more marketable.

A complete journey from China to the Mediterranean took anywhere from two to three years, but almost no one actually made the full trip. Goods changed hands dozens of times as they moved westward, with different merchants handling each segment of the route.

Historical records mention few women traders by name, but archaeological evidence shows women ran businesses in Silk Road cities, particularly widows who inherited their husband’s enterprises. They rarely traveled the dangerous sections themselves but operated from established urban trading posts.

Many shrank dramatically but didn’t disappear entirely. Samarkand survived as a regional center, though it never regained its medieval importance until modern tourism and its UNESCO designation brought new economic life based on heritage rather than transit trade.

Parts remain accessible through countries like Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and western China, though political restrictions and infrastructure gaps make following the complete historical path difficult. Some tour companies offer approximations, but modern borders and conflicts block several key sections entirely.