Pin

Pin Explorers and fur trappers have described it as the last great wilderness on Earth. It stretches for 13 million flat, featureless square kilometres from the snow and ice of the North Pole to the great northern forests. It is a cold, hard place in which to eke out a living, but large numbers of animals and plants do just that in this frozen desolation that is called the tundra.

Pin

Pin  Pin

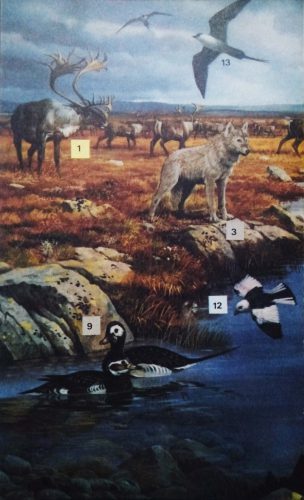

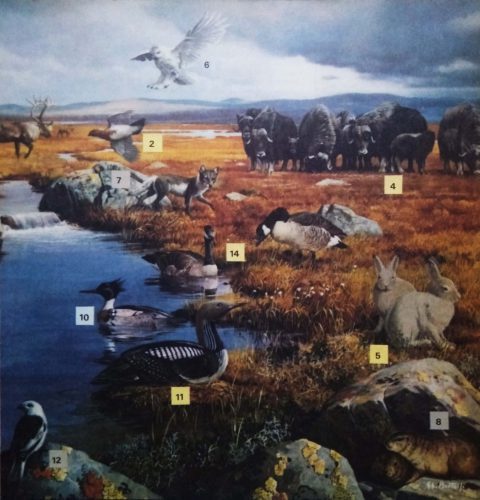

Pin Our picture shows the vast marshy plain of the North American tundra just before the big winter freeze. For nine long, empty, chilling months temperatures can drop below -60°C, and remorseless icy winds, carrying ice needles and snow blizzards, scour the frozen wastes, blanketing the vegetation with snow.

Brief summer

Summer, however, is brief and busy. During its three short months, the tundra becomes a dense green carpet of summer-time grasses and small flowering plants, packed together with spongy lichens and mosses, and dotted with isolated strands of willow and dwarf birch among countless small lakes and rivers. Every grey slab of rock, pushed up out of the ground, split and shattered by constant freezing and thawing, is brightened by patches of orange, red and yellow lichen. The dryer land is covered by the greyish-green and bushy reindeer moss, which is not a moss at all, but also a lichen.

During the Arctic’s brief summer it is almost always daytime. For the tundra in summer is the land of the midnight sun.

Among the lichens there is an explosion of colour as soon as spring arrives. Flax, white saxifrage, Arctic roses, dwarf dandelions, white stars of stitchwort, yellow patches of cinquefoil, red and golden poppies, purple saxifrage and bluebells all burst into flower. And among the flowers, there are thickets of crowberry and blueberry.

All the plants are dwarfed, lying close to the ground to avoid the ravages of the fierce Arctic winds and the abrasive action of ice and snow.

The greater part of a tundra plant is below the surface, but the root is long and shallow, prevented from pushing downwards by the frozen soil. Thirty centimetres or so below the surface of the soil is permanently frozen throughout the year. After the annual summer thaw, this subterranean ice-block prevents the surface water from draining away and the tundra becomes a trackless marsh covered by acre upon acre of bog moss.

Insects are the most abundant tundra animals. Mosquitoes and blackflies, having overwintered as eggs and rapidly changed from larvae to pupae, emerge in unimaginable numbers from the tundra swamps.

But Man is not the mosquitoes’ main victim. Great herds of caribou or reindeer (1) trek ceaselessly from pasture to spongy pasture, feeding particularly on reindeer moss. If they stopped in one place, they would quickly overgraze the moss which grows at the extraordinarily slow rate of 1.6 mm a year. So to survive they must keep moving.

Pin

Pin Ptarmigan (2) often follow the shifting herds. During the winter the caribou paw the ground to expose the lichens and the ptarmigan take advantage of any food unearthed by the scraping hooves.

Pin

Pin Ptarmigan and caribou are favourite prey for the legendary predator of the North — the wolf (3). A wolf can sprint at 40 km/h and trot for hours on end at 8 km/h. Built for endurance, wolves usually hunt in packs with a highly developed social system, After a chase, they will raise their muzzles into the air and howl, the sound bringing together a widely separated pack. As each wolf returns, it wags its tail and whimpers, showing that it is friendly.

Pin

Pin In deepest winter, when caribou are scarce, having moved further south, a wolf pack may chance an attack against a herd of animals that might have walked straight out of the Ice Age.

Bull-like with long shaggy coats, they are musk-oxen (4). They are not true oxen at all, being more related to the chamois goat of Central Europe. When attacked by wolves, the adult bulls form a defensive square with calves and females on the inside. They lower their heads and rub their forelegs, producing a powerful odour which can be detected several hundred metres away. This seems to snap the herd out of its normal quiet state, ready to face the enemy with lowered heads and vicious horns.

Pin

Pin Another animal that stays in the Arctic all winter long is the Arctic hare (5). In the worst winter weather, it crouches in rocky crevices, venturing out only to nibble at some frozen plant leaves. As the autumn frosts strike so quickly, the fully ripe plants are quick-frozen, remaining green all year round, The Arctic hare has long pincer-like incisors for tweezering out these green stems and nipping off buds deep in the snow.

Pin

Pin  Pin

Pin  Pin

Pin Nevertheless the hare is probably not the most: hunted creature. This unfortunate title probably goes to the vole-like lemming (8). These little mammals live in a labyrinth of shallow tunnels. In winter, foxes can often be seen digging in the snow with their noses to find them.

Pin

Pin Lemmings are remarkable in the way their numbers rise and fall dramatically.

They breed twice a year, and rapidly build up their numbers until the tunnels become overcrowded and they just cannot find enough lichens, fungi, moss and carrion on which they feed.

When this happens, suddenly, at some invisible sign, they come out of their burrows in their thousands, and great armies of them march off across the tundra in search of new pastures. The predators have a gluttonous field-day. But the feast is short-lived. As the numbers of lemmings drops so does the number of predators.

Summer visitors

Throughout the long Arctic winter these few animal species scratch a living as best they can. Then, one long empty night, the silence is shattered by the yodelling whistle of the long-tailed duck or ‘old squaw’ (9). Through the early spring, it migrates north by night in loose flocks and descends on the tundra lakes to breed. Its arrival marks the start of spring, when the summer visitors come. They come in their millions.

Pin

Pin  Pin

Pin  Pin

Pin The loon quickly seeks out the best nest sites close to the water’s edge, for its legs are far back along its body, ideal for swimming but not for walking. So the bird inelegantly drags from nest to water and back with its belly scraping along the ground.

The unobtrusive little black-and-white snow bunting (12) betrays its presence with a piping ‘tihee’, as it flits from rock to rock, pausing for long periods and gripping the surface with tiny claws, braced against the buffeting of the wind.

Pin

Pin Skua

In winter the long-tailed skua (13) lives out at sea, but in the summer it flies north to nest. It is particularly dependent on the lemming. Somehow it seems to be able to sense how many lemmings there are going to be and lays its eggs accordingly. In a bad lemming year it may not nest at all; in a good year it lays more eggs, before the lemming swarms have actually emerged.

Pin

Pin Canada geese (14) always return to the area where they first hatched from the egg year after year. Their honkings and cacklings fill the air. They mate for life, and each pair seeks out flat meadow-like land, nesting as far from the next pair as possible. But even so, there may be as many as 40 nests per square kilometre.

Pin

Pin Nowadays one animal that used to be rare in the tundra can be seen in increasing numbers. This is Man. Recent discoveries of oil and other minerals have meant more people, bringing with them their paraphernalia of civilisation. If we are not careful the last great wilderness on Earth may be permanently scarred by misuse.

More About Tundra

The tundra is a vast and harsh biome located in the Arctic regions of the world, encompassing parts of Alaska, Canada, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden. Despite its freezing temperatures and extreme conditions, the tundra is home to a variety of fascinating animal species that have adapted to survive in this challenging environment.

One of the most iconic animals of the tundra is the polar bear (Ursus maritimus). These majestic creatures are well-suited to life in the Arctic with their thick layer of fat and white fur, which provides camouflage in the snowy landscape. They have adapted to swim long distances between ice floes and are excellent hunters, primarily feeding on seals. However, climate change and the melting of sea ice poses a significant threat to their survival.

Another well-known animal of the tundra is the Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus). These small, agile predators have thick fur that changes color with the seasons to blend in with the environment. They are masters of survival, able to withstand extremely low temperatures and survive on a diet that includes rodents, birds, and even carrion. Their dens provide shelter from the harsh weather and protect their young during long, cold winters.

Caribou, also known as reindeer (Rangifer tarandus), are a common sight in the tundra. These large, hoofed animals are highly adapted for life in the Arctic. They have thick fur and a unique nose that warms the air they breathe before it reaches their lungs. Caribou travel in large herds, migrating vast distances in search of food, which mainly consists of lichen and mosses. They are also preyed upon by wolves and bears, which keeps their population in check.

Musk oxen (Ovibos moschatus) are another species that call the tundra home. These large, shaggy animals are well-adapted to survive in the harsh winters. Their thick fur and layer of fat provide insulation against the cold temperatures, and they also have a unique behavior known as “circular defense,” where they form a defensive circle facing outward when threatened by predators. This protective behavior helps to deter would-be attackers, such as wolves or bears.

In addition to these larger animals, the tundra is also home to a variety of smaller creatures. Lemmings, for example, are tiny rodents that play a vital role in the ecosystem. Despite their size, they are incredibly resilient and have the ability to burrow beneath the snow to find food during the long winters. They are a critical food source for many predators in the tundra, such as owls, foxes, and stoats.

Birds are also abundant in the tundra, including species such as the snowy owl, ptarmigan, and Arctic tern. These birds have unique adaptations that help them survive in the extreme cold, such as feathered feet that act as snowshoes and thick layers of down feathers for insulation. Many species of birds migrate to the tundra during the summer months to breed and take advantage of the brief but bountiful summer season.

Overall, the tundra is a harsh yet fascinating biome that is home to a diverse array of animal species. These animals have evolved incredible adaptations to survive in the freezing temperatures, limited resources, and long periods of darkness. However, they are also facing significant challenges due to climate change and habitat destruction. Efforts to protect and conserve these unique ecosystems are crucial to ensure the survival of tundra animals for future generations.

Tundra animals have several adaptations that allow them to survive in extremely cold temperatures:

These adaptations allow tundra animals to endure and thrive in the extreme cold temperatures of their habitat.

Some of the most iconic animals that inhabit the tundra are:

These animals have developed various physical and behavioral adaptations to survive the extreme cold, limited food availability, and other challenges of the tundra environment.

Tundra animals interact with each other and their environment:

Tundra animals interact with each other and their environment in complex ways, contributing to the delicate balance of the tundra ecosystem. These interactions include predator-prey relationships, herbivore grazing patterns, and various other noteworthy interactions.

Predator-prey relationships in the tundra are crucial for maintaining population control and overall ecosystem stability. One of the most notable predator-prey interactions in the tundra is the relationship between Arctic wolves (Canis lupus arctos) and muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus).

Arctic wolves primarily rely on muskoxen as a food source, and they have evolved to be highly efficient hunters in the unforgiving tundra environment. These wolves often work together in packs to bring down large muskoxen, targeting weaker or younger individuals. This interaction not only regulates the muskoxen population but also affects the vegetation dynamics as the presence of wolves disturbs their grazing patterns.

Another predator-prey relationship in the tundra is between polar bears (Ursus maritimus) and seals, mainly ringed seals (Pusa hispida). Polar bears rely on seals as their primary food source and are adapted to hunt them on sea ice. They use their exceptional sense of smell to locate breathing holes of seals in the ice and ambush them when they emerge for air. Polar bears’ survival largely depends on their ability to hunt seals, and any disturbance in this interaction can have cascading effects throughout the food web.

In addition to predator-prey relationships, herbivore grazing patterns in the tundra are essential for maintaining plant diversity and overall ecosystem health. Caribou (Rangifer tarandus) herds play a vital role in this regard. In the summer, when the tundra becomes fertile with low-lying vegetation, caribou migrate in large herds to graze. As they move and feed, caribou trample and break up the moss and lichen cover, creating a more diverse plant landscape. This disturbance helps maintain the open tundra by preventing shrub encroachment and allowing for the survival of other plant species.

Moreover, the interactions between insects and plants in the tundra have noteworthy impacts. For instance, pollinating insects, such as bees and butterflies, play a crucial role in facilitating the reproduction of flowering plants. Their presence ensures successful pollination and the production of seeds, which contributes to the overall health and diversity of the tundra vegetation.

It is important to note that the delicate balance of the tundra ecosystem can be disrupted by various factors, such as climate change and human activities. As the tundra warms, changes in predator-prey dynamics and herbivore grazing patterns can occur. For example, the reduction of sea ice due to climate change may limit access for polar bears to hunt seals and force them to seek alternative food sources. These changes can have far-reaching consequences throughout the ecosystem, affecting not only the predator and prey populations but also the vegetation and other interacting species.

Tundra animals interact with each other and their environment through predator-prey relationships, herbivore grazing patterns, and other interactions. These interactions contribute to the delicate balance of the tundra ecosystem, regulating populations and maintaining biodiversity. However, these dynamics are vulnerable to disturbances, highlighting the importance of preserving the tundra and mitigating human impacts to safeguard this unique and fragile ecosystem.

Tundra animals undergo a range of physiological and behavioral changes in response to the extreme environmental conditions they experience during different seasons. Some of these changes include migration, hibernation, and changes in fur color:

Tundra animals may exhibit other adaptations like increased fat reserves to provide insulation and energy during winter, thickened fur or feathers for insulation, and specialized feeding behaviors to take advantage of available food sources. These adaptations allow tundra animals to survive and thrive in one of the harshest environments on Earth.

Frequently Asked Questions about Tundra Animals:

A tundra is a type of biome found in the Arctic and Alpine regions of the world. It is characterized by extremely cold temperatures, little to no trees, and a short growing season.

The tundra is home to a diverse range of animal species, adapted to survive in harsh conditions. Some commonly found animals include polar bears, Arctic foxes, reindeer, muskoxen, snowy owls, lemmings, and ptarmigans.

Tundra animals have several adaptations that allow them to survive in cold climates. They have thick fur or feathers to provide insulation, large fat reserves to keep warm, and compact bodies to reduce heat loss. Some animals even hibernate during the winter months.

Tundra animals have adapted to the limited food sources available in their environment. Herbivores like reindeer and muskoxen feed on grasses, mosses, and shrubs that can survive the cold. Carnivores like polar bears and Arctic foxes prey on marine mammals, fish, and small rodents.

Yes, the tundra is home to several predators. The most notable predator is the polar bear, which is at the top of the food chain in the Arctic. Other predators include Arctic foxes, wolves, wolverines, and snowy owls.

Yes, several species found in the tundra are considered endangered or vulnerable. This includes the polar bear, due to the loss of sea ice habitat caused by climate change. The Arctic fox and some migratory bird populations are also at risk.

Yes, many tundra animals migrate to find food and suitable breeding grounds. For example, caribou undertake one of the longest terrestrial migrations on Earth, traveling hundreds of miles to find food during the summer months.

Yes, some tundra animals, such as ground squirrels and arctic ground-dwelling birds, hibernate during the harsh winter months. They enter a state of torpor, lowering their body temperature and metabolic rate to conserve energy.

Tundra animals have adaptations to deal with the limited availability of water. They have the ability to conserve water in their bodies and obtain moisture from their diet. Some animals also have specialized kidneys that concentrate urine to prevent excessive water loss.

Yes, tundra animals have developed various unique adaptations to survive in the harsh conditions. For instance, the Arctic fox has a thick, white fur coat in winter to camouflage itself, while the reindeer has large hooves to help them navigate in snow. Polar bears also have a layer of blubber to insulate themselves from the cold.