Pin

Pin Photo courtesy Business Wire

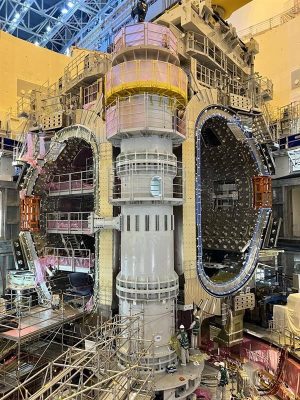

Synopsis: Away from crowded cities, a vast scientific experiment is unfolding in southern France. ITER, a global fusion research project supported by 35 nations, is moving from theory toward real-world testing. Its aim is not instant electricity, but proof that fusion energy can be controlled at scale. Success could influence future energy systems for decades. Even setbacks would leave behind knowledge shaped by patience, cooperation, and long-term thinking.

Near the small French town of Cadarache, the countryside looks much as it always has. Hills roll gently, stone houses age gracefully, and daily life carries on without urgency. Yet beneath this calm surface, a remarkable collaboration is taking shape—one that brings together nations that often disagree on nearly everything else.

Here, scientists and engineers are building a machine designed to recreate the same physical process that powers stars. Not a star itself, and not a power plant, but a carefully controlled experiment meant to test whether fusion energy can be sustained reliably on Earth. The work is quiet, deliberate, and slow by design—because mistakes at this scale tend to be unforgettable.

Table of Contents

Why This Project Was Attempted at All

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy IndianDefenceReview

Human progress has always been powered by energy, and every era has paid a price for how that energy was obtained. Coal and oil brought growth but polluted air and altered climate patterns. Nuclear fission reduced emissions but raised concerns about waste and long-term safety. Fusion entered the discussion as a different kind of possibility.

Fusion offers energy without combustion and without the long-lived radioactive byproducts associated with traditional nuclear reactors. The appeal is obvious, but the challenge is formidable. Fusion reactions demand extreme heat, precise control, and materials pushed far beyond everyday limits.

ITER exists to answer a single, practical question: can this process be controlled long enough, safely enough, and efficiently enough to matter outside laboratory experiments? That question proved too large, expensive, and uncertain for any one country to tackle alone.

What Makes Fusion a Different Kind of Nuclear Science

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy ITER

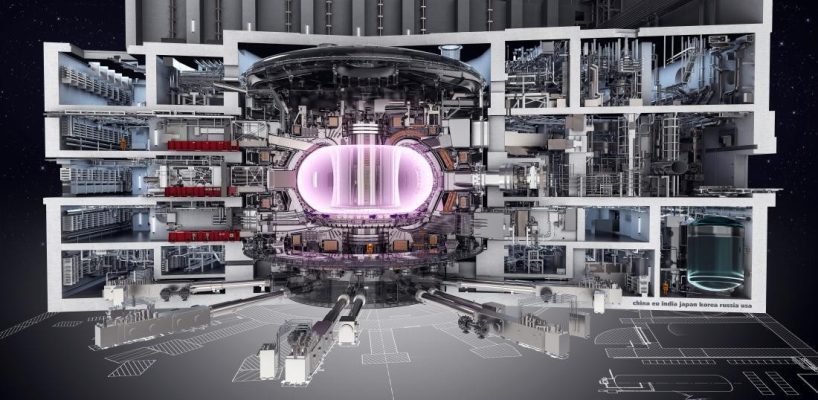

Fusion behaves unlike the nuclear power plants most people recognize. Instead of splitting heavy atoms, it forces light atoms—forms of hydrogen—to merge. When conditions are correct, energy is released. When they are not, the reaction stops on its own.

This makes fusion inherently stable, but extremely difficult. The fuel must be heated to extraordinary temperatures and held in place without touching physical walls. ITER uses a ring-shaped device called a tokamak, where powerful superconducting magnets guide superheated plasma in a carefully controlled loop.

On paper, the physics is well understood. What remains uncertain is how these systems behave together, at full scale, over extended periods. ITER is built to observe that behavior directly.

Why Southern France Was Chosen

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy ITER

The location of ITER was not selected for drama or symbolism. It was chosen for reliability. The region offers stable geology, strong infrastructure, and access to decades of nuclear engineering experience.

France also provided legal and political frameworks suited for international collaboration. Hosting dozens of nations under one project requires agreements that reduce conflict rather than create it. Roads could be modified, power grids expanded, and security maintained without constant negotiation.

At first, the project felt foreign to nearby communities. Over time, it became familiar—another part of the landscape, though one marked by an unusual mix of languages and expertise.

A Scale That Resists Simple Description

ITER’s size is best understood through logistics rather than numbers. Components are manufactured across continents, then shipped by sea, river, and specially reinforced roads. Some deliveries move slower than walking pace.

Inside the reactor building, the scale reverses. Massive parts must align with extraordinary precision. Small deviations can ripple outward, causing delays measured in months or years.

This combination—enormous size paired with microscopic tolerances—defines the project. Nothing fits casually. Every step demands confirmation.

The People Behind the Structure

Despite the steel and machinery, ITER is fundamentally a human effort. Thousands of specialists contribute—physicists, engineers, technicians, planners, translators. Differences in standards, training, and expectations are unavoidable.

Progress often slows not because of failure, but because agreement takes time. Measurements are debated. Procedures revised. Assumptions questioned.

Many contributors know they may never see the project’s final results. They continue anyway, motivated by the belief that careful work today creates options tomorrow.

Delays, Costs, and Public Scrutiny

ITER has faced criticism for schedule changes and rising costs. These concerns are real and widely acknowledged by project leadership. Fusion research has repeatedly revealed challenges that could not be predicted fully in advance.

Each redesign reflects lessons learned rather than abandoned effort. Materials behave differently under extreme conditions. Systems interact in unexpected ways.

Large scientific projects often appear inefficient while underway. Their value tends to become clearer only after their outcomes—successful or not—are absorbed into future work.

The Sensitive Phase Ahead

ITER is now entering a phase where independent systems must operate together. Cooling, magnetic control, structural integrity, and software coordination all become equally important.

Early plasma tests will not generate electricity or dramatic visuals. Their purpose is stability—confirming that the reactor can safely create and control plasma as designed.

At this stage, caution is not hesitation. It is the only sensible approach.

What Success Would Actually Mean

Success would not bring immediate fusion power plants. It would provide confidence. Proof that sustained fusion is achievable beyond short experiments.

That confirmation would encourage future projects aimed at producing electricity. It would influence long-term planning rather than replace existing energy sources overnight.

Energy systems change slowly. Fusion’s promise lies in durability, not speed.

What Failure Would Still Leave Behind

Even if ITER does not meet all expectations, its contributions would remain. Advances in materials science, robotics, plasma control, and international project management would continue to influence other fields.

Understanding limits is valuable knowledge. It narrows uncertainty and guides better designs.

In science, few efforts are truly wasted.

Why the World Continues to Pay Attention

Energy security shapes global stability. Fusion offers the possibility of power less dependent on fuel transport or geographic advantage.

ITER also stands as evidence that cooperation can persist even when political relationships strain. Shared challenges tend to encourage shared solutions.

The project is less about competition and more about continuity.

A Quiet Legacy in the Making

Years from now, ITER may be remembered not only for its machinery, but for its restraint. It chose careful progress over spectacle.

Children growing up nearby already see international collaboration as ordinary. That may prove as influential as any technical result.

Some projects matter because they were pursued thoughtfully, regardless of outcome.

FAQs

No. It is a research reactor designed to test fusion conditions, not supply power to the grid.

Fusion reactions stop automatically if conditions fail, making them far safer than traditional nuclear systems.

The project pushes engineering and materials beyond existing limits, requiring redesigns and careful testing.

No. Fusion is expected to complement renewable energy, not replace it.

If results are positive, demonstration reactors could follow within a few decades.