Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Kumiko Designs

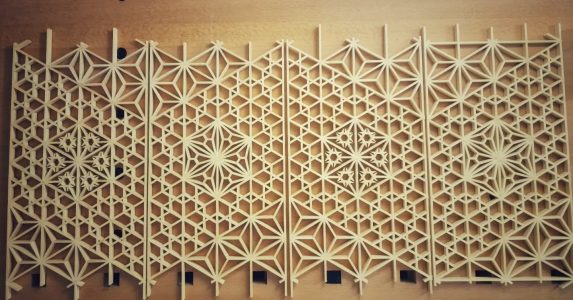

In a quiet workshop in Kyoto, morning light filters through a wooden screen, casting geometric shadows across the floor. The screen itself is a marvel of engineering and artistry—hundreds of thin wooden strips interlocked at perfect angles, creating patterns that seem to breathe with the changing daylight. This is kumiko, an ancient Japanese technique that has shaped the country’s architectural identity for over a millennium.

The craft operates on a principle that seems almost impossible at first glance. Wooden strips, some as thin as three millimeters, fit together without a single nail, screw, or drop of adhesive. The secret lies in precise angles and carefully calculated joints that hold themselves together through friction and geometry alone. What begins as raw cypress or cedar wood becomes intricate lattices that are both structurally sound and visually stunning.

This traditional art form has found new life in contemporary spaces around the world. Modern architects and furniture makers are rediscovering kumiko’s potential, incorporating these delicate patterns into everything from room dividers to cabinet doors. The technique represents something deeper than mere decoration—it embodies a philosophy of craftsmanship where patience, precision, and respect for natural materials create lasting beauty.

Table of Contents

The Foundation of Precision

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Vincew Cook

The journey into kumiko begins with understanding wood itself. Unlike metal or plastic, wood is a living material that continues to move even after being cut. It expands with humidity, contracts in dry conditions, and each species behaves differently. Cedar breathes more than cypress. Hinoki holds its shape with remarkable stability. Craftsmen must know these characteristics intimately before making a single cut.

The basic building block is deceptively simple: a wooden strip called a kumiko-zai. These strips are milled to exact dimensions, typically ranging from three to six millimeters in thickness. The width varies depending on the pattern being created, but consistency is everything. Even a half-millimeter variation can throw off an entire panel. Traditional workshops use hand planes to achieve this precision, shaving wood until the strips are uniform along their entire length.

What makes kumiko structurally possible is the groove system. Thicker frame pieces contain narrow channels—called jigumi—that hold the delicate lattice work. The kumiko strips slide into these grooves and interlock with each other at calculated angles. The entire assembly becomes self-supporting, with each piece helping to lock its neighbors in place. When done correctly, you can lift a completed panel and feel its surprising rigidity, despite being made entirely of thin wooden strips holding hands across empty space.

Patterns That Tell Stories

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Shiozawa Artwork

The asanoha pattern appears everywhere in traditional Japanese design—on kimono fabrics, temple ceilings, and of course, kumiko screens. The name means “hemp leaf,” and the six-pointed star motif mirrors the shape of hemp plant leaves. This isn’t just aesthetic borrowing. Hemp grows quickly and resiliently in Japanese soil, and parents traditionally dressed their children in asanoha-patterned clothing as a symbolic wish for healthy, strong growth. When this pattern appears in kumiko, it carries centuries of cultural meaning woven into wood.

Creating the asanoha requires understanding equilateral triangles and hexagons. The strips meet at sixty-degree angles, and each intersection must be perfectly calculated. The center of each star connects to six surrounding stars, forming an infinite tessellation that could theoretically extend forever. Craftsmen begin by establishing a base grid, then weave additional strips through at opposing angles. The overlapping creates the distinctive star shape, with small triangular gaps between each point that allow light to filter through.

Another beloved pattern is the kagome, which means “bamboo basket.” This design uses the same sixty-degree angles but arranges them differently, creating a honeycomb effect that feels more open and airy than the asanoha. Traditional fishing baskets used this weaving pattern because it provided strength while remaining flexible. In kumiko form, the kagome brings that same sense of organized openness—solid enough to provide privacy, open enough to let air and light flow freely through a room.

The Logic of Angles and Joints

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Shiozawa Artwork

Every kumiko pattern relies on a handful of fundamental angles that appear repeatedly throughout the design. The most common are thirty, forty-five, and sixty degrees—angles that allow wooden strips to intersect cleanly and create stable geometric shapes. These aren’t arbitrary choices. They’re the angles that triangles, squares, and hexagons naturally produce, and these shapes happen to be the most structurally efficient forms in nature. Honeybees understood this millions of years ago when they started building hexagonal cells. Kumiko craftsmen arrived at the same conclusion through centuries of experimentation.

The joints themselves are marvels of engineering hidden in plain sight. When two strips cross, they don’t simply overlap—they interweave through carefully cut notches. The most basic joint is the aitori, where strips of equal thickness cross at right angles. Each piece has a half-lap cut exactly at its midpoint, allowing them to nest together flush. The fit must be snug enough to hold without adhesive, yet loose enough that the wood can expand slightly with seasonal humidity changes without cracking.

More complex patterns require the miter joint, where strips meet at their ends rather than crossing through their centers. These joints demand even greater precision because there’s less surface area for friction to grip. A craftsman will cut the angle, test the fit, then shave away micrometers of wood until the joint slides together with gentle resistance—what experienced hands recognize as the perfect tension. When a panel contains hundreds of these joints working together, the cumulative effect creates a structure that’s remarkably strong despite its delicate appearance.

Tools of Quiet Precision

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy Kumiko Designs

The kumiko workshop contains tools that have barely changed in design for centuries. The most essential is the dozuki saw—a thin-bladed pull saw with teeth so fine they number over twenty per inch. Unlike Western saws that cut on the push stroke, Japanese saws work on the pull, which allows for a thinner blade that creates a narrower cut. This matters tremendously when working with delicate strips where even a millimeter of wasted wood can alter the final dimensions. The saw produces cuts so clean that the wood surface looks almost polished, eliminating the need for sanding that might round over the sharp edges needed for tight joints.

Equally important is the marking gauge, a simple device that scribes parallel lines along the wood grain. Traditional versions use a sharp knife edge rather than a pencil because pencil lines have thickness—sometimes half a millimeter wide—which introduces imprecision. The knife scores the wood fibers, creating a groove that guides the saw blade and prevents tear-out. Many craftsmen also use a combination square set to common kumiko angles, allowing them to mark thirty and sixty-degree cuts repeatedly without recalculating each time. These tools might look primitive next to modern laser-guided equipment, but they offer something digital tools cannot: direct feedback through the hands.

The workbench itself plays a supporting role in this precision. Traditional benches include built-in stops and holddowns that secure wood without metal clamps that might dent soft cypress or cedar. Small wooden wedges hold pieces firmly while allowing quick repositioning. Everything is designed to keep the work stable while the hands remain free to feel the wood, sense resistance, and make those tiny adjustments that separate adequate joinery from excellence. The entire system—tools, bench, and human sensitivity—functions as one integrated unit.

The Rhythm of Learning

Pin

Pin Photo courtesy of Shiozawa Artwork

Mastering kumiko requires a different relationship with time than most modern pursuits demand. Beginners often start with a simple four-way cross pattern—four strips intersecting at right angles to form a basic grid. Even this elementary exercise reveals the craft’s unforgiving nature. If the cuts are off by even a degree, the grid won’t sit flat. If the notches are too deep, the joints feel loose and wobbly. Too shallow, and the pieces won’t seat properly, leaving gaps that catch the eye. This immediate feedback teaches precision in a way that no instruction manual could convey.

The learning curve follows a pattern that experienced practitioners recognize. The first few months focus entirely on developing muscle memory for basic cuts and joints. Hands must learn to feel when a saw blade is wandering off course, when a chisel is biting too aggressively into the wood. During this phase, mistakes are constant teachers. A split piece of cypress reveals that the grain wasn’t considered before cutting. A joint that won’t quite fit shows that humidity changed the wood’s dimensions overnight. Each error becomes a lesson stored not just in the mind but in the hands themselves.

After perhaps a year of consistent practice, something shifts. The tools begin to feel like extensions of the body rather than separate objects being manipulated. The wood starts communicating its properties through subtle resistance and sound—a different tone when the saw cuts with the grain versus across it, a particular feeling when the blade enters dense winter growth versus softer summer wood. This intuitive understanding cannot be rushed or shortcut. It emerges only through repetition, attention, and the willingness to work slowly enough that each action registers fully in awareness.

Wood as Living Material

Understanding kumiko means understanding that wood never truly stops being alive. Even after a tree is felled, milled, and shaped into thin strips, the cellular structure continues responding to its environment. Wood cells act like tiny straws that absorb moisture from humid air and release it when conditions turn dry. This constant breathing causes the wood to expand across its width and contract again, sometimes by several percentage points over the course of a year. Kumiko craftsmen must design their joinery to accommodate this movement, allowing strips to shift slightly without the entire panel warping or cracking under stress.

Different wood species bring distinct personalities to kumiko work. Hinoki cypress, prized throughout Japan for its stability and pleasant fragrance, holds its dimensions better than most woods and resists rot naturally. Its tight, straight grain makes it ideal for the delicate strips that form intricate patterns. Cedar offers a warmer, reddish tone and slightly softer texture that’s easier to cut but requires more gentle handling during assembly. Japanese maple provides beautiful grain patterns but demands extra attention during seasonal transitions because it moves more dramatically than cypress. Choosing the right wood for a specific project and location isn’t just about aesthetics—it’s about predicting how the piece will behave over decades.

The finishing process respects this living quality rather than fighting against it. Traditional kumiko rarely receives heavy varnishes or polyurethane coatings that seal the wood completely. Instead, craftsmen might apply a light oil finish that penetrates the surface, enriching the color while still allowing the wood to breathe. Some pieces receive no finish at all, left natural to develop a patina over years of exposure to light and touch. This approach means kumiko panels age visibly, their color deepening and their surface developing a subtle luster that only time and use can create.

Light and Shadow in Daily Life

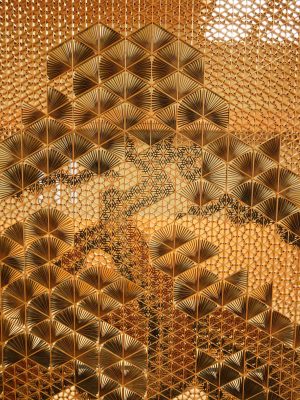

The true purpose of kumiko reveals itself not in the workshop but in the spaces where these panels come to live. Traditional Japanese homes use kumiko screens—called ranma—installed above sliding doors and in transom windows. These aren’t merely decorative additions. They serve a practical function in managing light and air circulation throughout the home. During summer months, when windows stay open for ventilation, the geometric patterns allow breezes to flow through while maintaining visual privacy between rooms. The open spaces between wooden strips create natural ventilation channels that help keep interiors comfortable without modern air conditioning.

The interplay between kumiko and natural light transforms throughout the day in ways that solid walls or glass never could. Morning sun streaming through an asanoha pattern casts sharp geometric shadows across tatami mats, creating temporary artwork that shifts and fades as the sun moves across the sky. By afternoon, when light enters at lower angles, the same pattern produces entirely different shadow formations. Evening light softens everything, and the wooden lattice becomes a warm silhouette against the fading daylight. This constantly changing visual experience means rooms feel alive and connected to the natural rhythms outside, even when doors remain closed.

Modern applications have expanded beyond traditional architecture while maintaining these light-filtering qualities. Contemporary restaurants use kumiko panels as room dividers that separate dining areas without creating the heavy isolation that solid walls impose. Architects incorporate kumiko into building facades where the patterns reduce harsh direct sunlight while still illuminating interiors with diffused natural light. Home designers install kumiko cabinet doors that hide contents while allowing air circulation, preventing the musty odors that can develop in closed storage. Each application demonstrates how this ancient technique addresses fundamental human needs for privacy, light, and connection to space in ways that feel both practical and quietly beautiful.

The Mathematics Behind Beauty

The geometric patterns in kumiko aren’t simply arranged by intuition—they follow mathematical principles that have fascinated scholars for centuries. The most fundamental concept is tessellation, where shapes fit together to cover a surface completely without gaps or overlaps. Regular tessellations use only one type of polygon repeated infinitely, and only three shapes can do this: triangles, squares, and hexagons. Kumiko exploits this natural limitation by building patterns around these three forms, knowing they’ll always resolve into stable, repeating designs that can extend as far as needed without encountering mathematical impossibilities.

The asanoha pattern demonstrates what mathematicians call a semi-regular tessellation—it uses two different shapes (hexagons and triangles) that alternate in a consistent arrangement. Each six-pointed star is actually a hexagon with its sides pushed inward, surrounded by twelve small equilateral triangles. This arrangement isn’t arbitrary. It emerges naturally when you connect the centers of adjacent hexagons in a honeycomb pattern. Ancient craftsmen discovered this relationship not through equations but through patient observation and experimentation, finding what worked by making thousands of pieces until the underlying mathematical truth revealed itself through wood.

The sixty-degree angle that dominates many kumiko patterns has special properties that make it particularly suited for woodworking. When three pieces meet at sixty degrees, they create perfect equilateral triangles—shapes where all angles and sides are equal. This equality distributes stress evenly across joints rather than concentrating it at weak points. The angle also divides evenly into a full circle, meaning patterns can rotate and repeat six times around a center point while maintaining perfect symmetry. This mathematical harmony translates into structural stability, proving once again that beauty and function often share the same geometric foundations.

Preservation Through Practice

The survival of kumiko as a living craft faces challenges that extend beyond simply teaching techniques to new generations. Many traditional workshops in Japan have closed as younger people pursue careers in cities rather than continuing family trades that demand years of apprenticeship for modest financial returns. The knowledge isn’t just about cutting angles correctly—it encompasses an entire ecosystem of understanding about wood suppliers, seasonal timing for harvesting timber, and regional variations in style that have developed over centuries. When a master craftsman retires without passing on this accumulated wisdom, entire branches of the tradition can disappear within a single generation.

Some preservation efforts focus on documentation, creating detailed videos and manuals that capture kumiko techniques before they vanish. While valuable, these archives cannot fully replace the experience of learning directly from someone who has spent forty years feeling how wood responds to tools. The subtle adjustments a master makes without conscious thought—compensating for a slight variation in wood density, or recognizing when a blade needs sharpening by the sound it makes—these skills transfer most effectively through direct observation and correction. A student working beside a teacher receives hundreds of tiny course corrections that collectively shape proper technique in ways that video tutorials struggle to replicate.

Yet hopeful signs suggest kumiko may be entering a revival period. International interest has grown as architects and designers worldwide discover the technique’s aesthetic and functional possibilities. This attention brings fresh economic opportunities that make the craft more viable as a profession. Several schools in Japan now offer short-term intensive courses alongside traditional multi-year apprenticeships, creating pathways for people to engage with kumiko at different levels of commitment. The internet allows contemporary practitioners to share innovations and problem-solving strategies instantly across continents, building a global community around this distinctly Japanese tradition.

Contemporary Adaptations and Innovations

Kumiko has begun appearing in unexpected places as contemporary makers experiment with its principles beyond traditional screens and transoms. Furniture designers now incorporate kumiko panels into headboards, cabinet fronts, and table bases where the geometric patterns add visual interest while maintaining structural integrity. Some creators push the boundaries further by using non-traditional materials—thin strips of bamboo, acrylic, or even metal—to create kumiko-inspired patterns that honor the geometric logic while adapting to modern aesthetics. These experiments demonstrate that the underlying principles of precise joinery and mathematical patterning can translate across different materials and cultural contexts.

The technique has also found surprisingly practical applications in acoustic engineering. The regular spacing of kumiko strips creates a diffusion pattern that scatters sound waves rather than reflecting them directly back into a room. Recording studios and concert halls have begun installing kumiko-style panels as functional art that improves sound quality while adding warmth that acoustic foam panels cannot match. The hollow spaces between strips trap certain frequencies while allowing others to pass through, creating natural sound modulation without electronic processing. This marriage of ancient craft and modern acoustics shows how traditional techniques often contain solutions to contemporary problems, waiting to be rediscovered and applied in new contexts.

Digital fabrication technology has introduced both opportunities and debates within the kumiko community. Computer-controlled routers and laser cutters can produce kumiko joints with perfect consistency far faster than human hands can achieve. Some practitioners embrace these tools as natural evolutions that make the craft more accessible and economically viable. Others argue that machine production removes the essential human element—the slight variations and adaptive problem-solving that give handmade kumiko its unique character. Perhaps the answer lies somewhere between, using technology for repetitive precision work while reserving the assembly and fine-tuning for human judgment and sensitivity.

The Philosophy of Patience

At its deepest level, kumiko teaches something more profound than woodworking technique—it offers a counter-narrative to the speed and efficiency that dominate contemporary life. Creating even a small kumiko panel requires hours of focused attention where rushing produces immediate failure. A saw blade pushed too quickly wanders off the cut line. A joint assembled without testing splits the delicate wood. The craft enforces slowness not as an aesthetic choice but as a functional requirement, and this enforced patience often transforms practitioners in unexpected ways. Many report that the concentration required for kumiko quiets the restless mental chatter that usually fills their days, creating a meditative state that arrives naturally through absorption in precise physical work.

The relationship between maker and material in kumiko differs fundamentally from manufacturing processes that force materials into predetermined shapes through heat, pressure, or chemical transformation. Kumiko asks the craftsman to work with wood’s natural properties rather than against them—to notice grain direction, to feel moisture content, to respect the boundaries of what thin strips can withstand before breaking. This respectful collaboration produces results that feel organic even when arranged in rigid geometric patterns. The wood retains its essential character throughout the process, never disguised under thick paint or buried beneath veneers. What you see in finished kumiko is honest material, honestly joined, creating beauty through clarity rather than concealment.

Perhaps this explains why kumiko continues to resonate across cultures and centuries. In an age of disposable products designed for obsolescence, kumiko represents permanence achieved through patient craft. The joints grow tighter as wood seasons and stabilizes over years. The patterns remain visually engaging because they’re based on mathematical truths rather than passing trends. When light filters through these wooden geometries, it connects contemporary rooms to the same quality of illumination that filled temple halls centuries ago—proof that some forms of beauty transcend their moment and speak to something enduring in human experience.

FAQs

Yes! Basic patterns are accessible with patience and proper tools. Start with simple cross patterns before advancing to complex designs like asanoha.

A quality pull saw, marking gauge, chisel set, and hand plane—around $200-300 for decent starter tools that will last years with proper care.

Not at all. While hinoki cypress is traditional, any straight-grained hardwood works. Walnut, maple, and cherry produce beautiful results in kumiko patterns.

A simple 30cm square panel might take 10-15 hours for intermediate skill levels. Complex patterns with hundreds of pieces can require 40+ hours of focused work.

Absolutely! Many traditional screens feature multiple patterns in different sections, creating visual variety while maintaining overall harmony through consistent wood species and dimensions.