Pin

Pin Every day newspapers, books and magazines — millions and millions of them — carry the printed word and picture to each and every one of us. Printing is a vital part of our lives. Through it we are informed, amused, guided and taught. Through printing, knowledge of all kinds has spread widely. Today it is hard to imagine a time when there was no printing. And yet that time was not so very long ago…

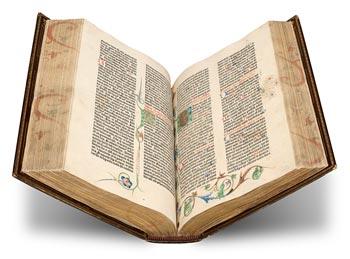

In the relatively short history of printing, one figure stands out — Johann Gutenberg. He was a German who worked at Mainz and Strasbourg in the middle years of the 15th century. Gutenberg was a goldsmith by trade, and it was his knowledge of working with metals that was to lead to the single most important invention of all — moveable type.

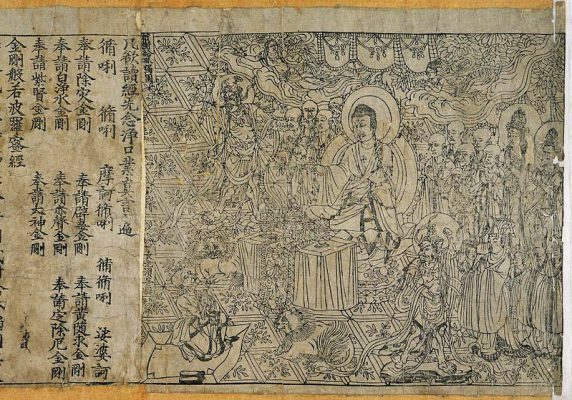

Printing — that is making a number of copies from one original by taking an impression on paper or something similar — was not unknown in Gutenberg’s time. The Chinese were printing books in the 9th century A.D., and the technique probably spread to Europe from the East after the traveller Marco Polo brought back ideas and techniques he and his companions had seen.

But this early printing was printing by blocks, the same principle as a simple potato print or lino-cut print. A picture and text would be laboriously carved into a block of wood and a number of prints made by inking the ‘page’ of matter thus formed. One block was for one page and could only be used for that page. If a mistake were made during the carving, the block. had to be scrapped and restarted. It was the same with handwritten books — a single mistake and a page was ruined.

Pin

Pin The Chinese were pioneers in printing and paper-making. Our above illustration shows a page of the Diamond Sutra, the oldest surviving printed book, dating from A.D. 868. Wood blocks were carved back-to-front with a raised image and inked. Paper was then pressed flat onto the picture or writing. But with one block for each page the method was very time-consuming.

Gutenberg changed all this by the brilliant notion of making each letter to be printed — the type — moveable. This meant that any word could be made up, a page printed and then the type dismantled to make up another page.

Gutenberg did this so carefully that each block (or ‘body’) of metal type was identical in size to the next. When a number of letters were assembled to form a word, and a number of words a line, they all were exactly level with each other giving an even impression.

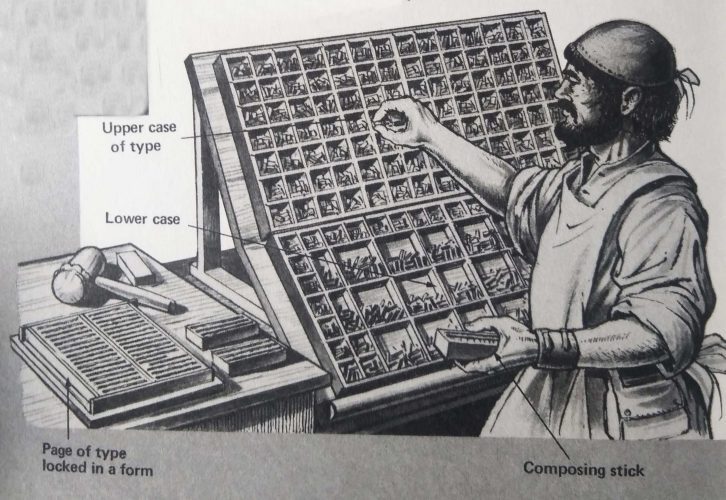

Type was cast for every letter of the alphabet. A number of copies of, each were made and put in order a special box called a ‘case’ so the typesetter (or compositor) could select what he needed. A Two boxes were used, the one at the top, the ‘upper case’, for capitals letters, the one at the bottom for ‘lower case’. Once the words and lines had been composed these were locked together in pages — several pages at a time — and laid flat facing upwards for inking.

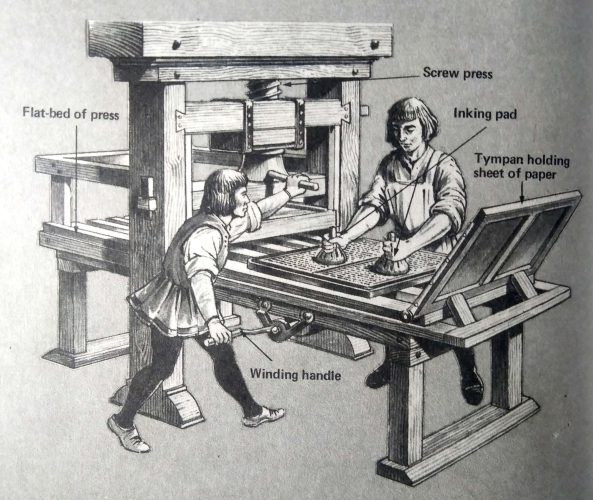

Gutenberg realised that this ‘letter-press’ process needed a system for pressing the paper to the inked type so he adopted the familiar screw-type machine used by winemakers to press their grapes. Using this method Gutenberg printed his first book, the famous Gutenberg Bible, which was published in 1455.

Pin

Pin  Pin

Pin But not only did moveable type allow many copies of this and other books to originate from Gutenberg’s press, it also allowed the printer to ‘proof’ each page before he finally printed a number of copies. By inking the type and pressing one sheet down, the machine operator could check to see whether the compositor had done his job properly. Any misspellings or omitted letters could be corrected before the full ‘run’ was made.

After Gutenberg’s astounding invention, Germany became the centre of printing. Very soon though the technique had spread to other countries in Europe.

The man responsible for introducing the new letterpress to England was a merchant, William Caxton, whose first book (printed on a press near Westminster Abbey) was The Sayings of the . Philosophers in 1477.

Pin

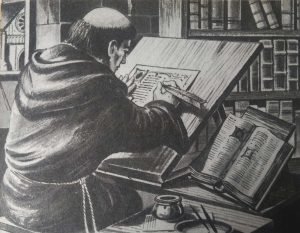

Pin Early books (which could only be read by a small number of wealthy people and scholars) were not, printed but handwritten. It was a slow and painstaking operation for the scribes and copyists who were often monks.

Pin

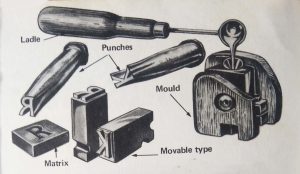

Pin Gutenberg made his type by first cutting a steel punch for each letter. This was banged into matrix of soft bronze, cutting an indented copy of the letter. The matrix was then put in a mould hot metal poured in. When this hardened it was removed from the matrix, a slim metal block with a raised letter on one end — the type.

Caxton was energetic and industrious, printing in all nearly one hundred works including translations. In particular he tended to concentrate not on Latin texts — as did so many Continental printers — but English ones including great classics such as Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales and Malory’s Morte d’ Arthur.

Many of the early books were illustrated. Here the technique was the old one of wood blocks, carefully carved and then locked into the frame of type ready for inking. The early printers were also very interested in experimenting with different styles of lettering in type — ‘typefaces’ — and some of the designs produced hundreds of years ago are still used to this day.

The well stocked printer would carry then, as he does now, different typefaces for different jobs. Each full alphabet of one style is called a ‘fount’ (pronounced – font).

Pin

Pin The compositor or typesetter sets the type correctly in the composing stick. The type case had two parts — the upper case for capital letters and the lower case for small letters. The lines of type were then laid flat and locked in wooden boxes called forms.

Pin

Pin A flat-bed screw press of the type used by Caxton and Gutenberg. The sheet of paper was laid flat over the inked type in the form. This was then wound into place under the screw press. Pressure was applied to obtain an even impression. The printed sheet was removed — but only by someone with clean hands!

But don't forget... there could be no printing without paper

Pin

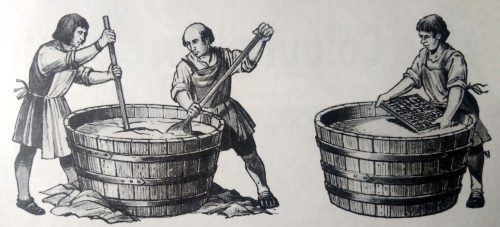

Pin True paper was invented by the Chinese about 2000 years ago. Their basic method reached Europe around A.D. 1200. Old rags were boiled up, and then beaten and stirred with lots of water to make a pulp (above left). A fine wire sieve was then dipped in the pulp and removed horizontally. A layer of pulp was left on the sieve as the water drained through the mesh (above right).

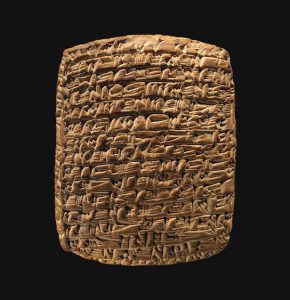

Hand in hand with the development of printing went efforts to improve the paper. While books were still being hand written, paper was not always necessary. Parchment made from animal skins that had been rubbed smooth and thin was sometimes used by the monks and copyists. Before that, papyrus made from reeds had been used by the early Egyptians, while the earliest writing material of all was simply tablets of baked clay.

The ingenious Chinese devised a method of chopping up rags, mixing the pieces with water to form pulp, and pouring this onto a bamboo mat through which the water drained leaving a sheet of wet fibres. Once dry this sheet became suitable for writing on. Eventually this pulp process found its way to Europe where hand-made paper, and later machine-made paper, produced using wood pulp were developed. A technique was later devised for making paper not just in small single sheets but long lengths.

Hungry

The new printing presses were hungry for paper, and each sheet printed could contain two, four or eight pages of the finished book. So paper had to be big enough, plentiful enough and of just the right absorbancy for the inks the ever-experimental printers were trying out.

With the invention of printing with moveable type changes took place that could not have been contemplated earlier. Books were cheaper and more easily obtainable so ideas were able to spread more quickly. The forerunners of today’s newspaper began to emerge to spread news and opinions far and wide.

Gutenberg’s genius had started a movement that was to grow and grow. And yet — for all the advances in man’s knowledge nothing in the history of printing was to surpass in originality his moveable type press.

It was not until hundreds of years later that the next major steps forward were taken.

The Gutenberg Bible Video

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, is one of the most influential and important books in the history of printing and the first major book printed using movable type in the Western world. It was produced by Johannes Gutenberg, a German goldsmith, inventor, printer, and publisher in the 15th century.

Gutenberg started working on the Bible around 1450 and completed the printing process in 1455. The book consists of two volumes, each containing 1,286 pages, printed using a printing press invented by Gutenberg himself. The text is printed in Latin using Gothic script, which was the standard writing style at that time. The paper used for the Bible was made from rag fibers, which ensured its durability.

The Gutenberg Bible is known for its aesthetic appeal and high quality, both in terms of the printing and the craftsmanship. The text is organized in two columns per page with 42 lines per column, hence the name “42-line Bible”. The layout of the text was carefully planned to make the Bible visually appealing and readable. It includes ornamental initials and decorative borders, which were added by hand after the initial printing. Some copies were also embellished with hand-painted illuminations, enhancing their artistic value.

Printing the Bible was a monumental task that required meticulous planning and attention to detail. Gutenberg had to design and cast individual metal type pieces for each letter, number, punctuation mark, and symbol used in the text. These individual metal pieces, known as movable type, were then assembled into lines and pages, inked, and pressed onto the paper. Gutenberg’s invention of movable type allowed for faster and more efficient printing, revolutionizing the production of books.

The Gutenberg Bible was initially produced in a limited edition of approximately 180 copies, each of them taking months to produce. This Bible was primarily intended for use in churches and monasteries, and it played a significant role in spreading literacy as it made the Bible more accessible to a wider audience. Prior to its invention, books were hand-copied by scribes, which was a time-consuming and expensive process. The Gutenberg Bible made books more affordable and triggered a revolution in printing and the mass production of books.

Today, only around 50 copies of the Gutenberg Bible are known to survive, making it an extremely rare and valuable book. These copies are scattered across various libraries, museums, and private collections around the world. The Gutenberg Bible is recognized as a masterpiece of printing and a symbol of the Renaissance period. Its significance lies not only in its historical and cultural value but also in the impact it had on literacy, education, and the dissemination of knowledge.

Gutenberg's printing press technology had a significant impact on the production and accessibility of religious texts, particularly the Bible, during the Renaissance period. Here are some of the ways it influenced this field:

Gutenberg’s printing press technology revolutionized the production and accessibility of religious texts, especially the Bible, during the Renaissance. It increased production, lowered costs, standardized texts, fostered literacy, and enabled vernacular translations. These developments played a pivotal role in transforming religious practices, encouraging individual religious engagement, and shaping the religious landscape of the time.

The production of the Gutenberg Bible revolutionized bookmaking techniques in several ways. Firstly, Johannes Gutenberg introduced movable type printing, which allowed for faster and more efficient production of texts. This technique involved individual metal letters and characters that could be arranged and rearranged to create a text. Previously, books were handwritten or made using woodblock printing, which was time-consuming and limited in the number of copies that could be produced.

Gutenberg developed a more durable and flexible type of ink, which made printing clearer and more consistent. He also created a special press that applied even pressure to the paper, ensuring high-quality prints. These advancements in bookmaking techniques significantly increased the speed, accuracy, and affordability of producing books, making them more widely accessible to people.

Despite these groundbreaking advancements, Gutenberg faced several challenges in creating the first printed Bible. One of the primary challenges was the financial undertaking of the project. The production of the Gutenberg Bible required a substantial investment in materials, including metal type, ink, and high-quality paper. Gutenberg faced financial struggles throughout the project and even had to borrow money.

Another significant challenge was the sheer size of the Bible. The Gutenberg Bible consisted of two volumes, each with over 600 pages. Printing such a large book was complex and required careful attention to detail. Gutenberg had to personally oversee the production process, ensuring the alignment of the type, the consistency of the ink, and the overall quality of each page.

Gutenberg faced challenges in sourcing and training skilled labor to assist with the production. He had to find craftsmen who could create the metal type, engrave illustrations, and bind the finished books. The training and coordination of these artisans added to the difficulties and time required for the project.

Gutenberg faced challenges related to distribution and marketing. As the first printed Bible, the Gutenberg Bible needed to find buyers, particularly wealthy patrons or institutions. Gutenberg faced competition from scribes and the resistance of those who believed traditional handwritten books were superior. He also had to navigate the complex network of book trade and distribution to ensure the wide availability and success of his printed Bibles.

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, is the first major book printed in the Western world using movable metal type. It was printed by Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz, Germany, between 1452 and 1455. Here are the distinguishing features and characteristics of the Gutenberg Bible:

1. Physical Appearance:

- Size: The Gutenberg Bible is a large folio-size book, measuring approximately 16.5 x 12 inches.

- Typeface: It was printed in a typeface that imitated the handwritten Gothic script prevalent at the time, known as Blackletter or Textura.

- Layout: The text is laid out in two columns, with 42 lines of text on each page. Hence, it is also known as the 42-line Bible.

- Paper: The Bible is printed on high-quality rag paper, which was more durable than the parchment used for handwritten manuscripts.

- Rubrication: The text is embellished with rubrication, where chapter numbers, headings, and initial letters are hand-painted in red ink.

- Illumination: While most copies of the Gutenberg Bible are unadorned, some copies feature elaborate hand-painted illuminations, including colorful initials and decorative borders.

2. Content:

- Language: The Gutenberg Bible is printed in Latin, which was the standard language for religious texts and scholarship at the time.

- Bible Text: It contains the complete text of the Latin Vulgate translation of the Bible, which was the standard biblical text used in the Western Christian Church.

- Missing Parts: Most copies of the Gutenberg Bible lack the Book of Revelation due to a production error, resulting in only 66 books instead of the usual 73 in a complete Bible.

- Commentary: It includes interlinear and marginal glosses, which function as commentary, helping readers understand difficult passages.

- Two Volumes: The Gutenberg Bible is usually printed in two volumes known as ‘Gutenberg A’ and ‘Gutenberg B.’ Each volume covers specific sections of the Bible, such as the Old Testament and the New Testament.

- Colophon: At the end of the book, there is a colophon, a statement of publication details, mentioning Gutenberg as the printer and the city of Mainz.

The Gutenberg Bible is not only seen as a major technological achievement in printing but also a work of art that revolutionized the dissemination of knowledge and had a profound impact on the history of books and reading.

Frequently Asked Questions: The Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible, is the first major book printed using movable type in Europe. It was created by Johannes Gutenberg in the 15th century, specifically between 1452 and 1455. This Bible is renowned as one of the most significant works in the history of printing, marking the beginning of the printing revolution and the dawn of mass communication.

There were originally around 180 copies of The Gutenberg Bible printed, with 145 in Latin and 35 in German. However, due to the passage of time and various circumstances, only around 49 copies have survived to this day, with each copy consisting of two volumes. Some copies are complete, while others are missing a few pages.

The Gutenberg Bible holds immense historical and cultural significance. It revolutionized the way books were produced and distributed, making knowledge more accessible to the masses. This was a fundamental step towards the dissemination of ideas and the democratization of information. The Gutenberg Bible is also regarded as a masterpiece of craftsmanship, demonstrating Gutenberg’s innovative printing techniques and his meticulous attention to detail.

The printing process used by Johannes Gutenberg for The Gutenberg Bible is known as movable type printing. Gutenberg designed individual metal letters, punctuation marks, and spaces, which were then assembled and arranged to form words, sentences, and paragraphs. These assembled blocks, called type, were inked and pressed onto paper, creating a printed page. For each page of The Gutenberg Bible, Gutenberg would assemble the type in a large wooden frame known as a forme, which was then used in the printing press.

The pages of The Gutenberg Bible were printed on high-quality handmade paper, which was a significant expense during that time. The ink used was a mixture of carbon black, water, and gum, which allowed for a consistent and durable impression. The type was made of an alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, which enabled the type to withstand the pressure when pressed onto the paper.

The Gutenberg Bible is primarily housed in various prestigious libraries and institutions around the world. Notable locations where you can see a copy include the British Library in London, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris, and the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Germany. However, due to the rarity and value of The Gutenberg Bible, the copies are often on display for limited periods or kept behind protective glass.

The Gutenberg Bible is considered one of the most valuable books in the world. The few remaining complete copies are priceless, and their value is estimated to be in the range of tens of millions of dollars. In fact, a single leaf from The Gutenberg Bible can fetch hundreds of thousands of dollars in auctions. The high value is a reflection of its historical significance, rarity, and the immense effort put into its production.

Yes, parts of The Gutenberg Bible have been digitized and made available online by various institutions. Digital versions allow individuals to explore the Bible and examine the intricate details of the text and illustrations. It provides an opportunity for a wider audience to engage with this remarkable historical artifact. However, it is worth noting that experiencing the physical copy of The Gutenberg Bible in person offers a unique and awe-inspiring encounter with history.