Pin

Pin Golden Nanmu / Photo courtesy Unknown

Synopsis: Golden Nanmu, known as China’s “immortal wood,” stands among the rarest and most valuable timbers on Earth. Prized for over 2,000 years by emperors and nobility, this golden-hued wood resists rot, repels insects, and releases a subtle citrus fragrance that lasts for centuries. A single mature log can sell for more than $3 million. Once reserved exclusively for imperial palaces and tombs, Golden Nanmu’s unique properties and extreme scarcity have made it more precious than jade or gold in Chinese culture.

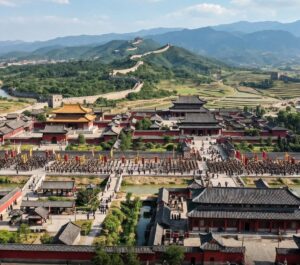

The Forbidden City in Beijing has seen emperors rise and fall, dynasties crumble, and revolutions sweep through its crimson gates. Yet the massive ceiling beams overhead remain unbothered by the passage of six hundred winters. The columns stand straight. The panels shine with a honey-colored glow that seems to come from within the wood itself.

There’s a reason for this stubbornness. The builders didn’t use ordinary timber. They used Golden Nanmu, a wood so valuable that common folk weren’t allowed to own it. Cutting down these trees without the emperor’s blessing carried a death sentence, which tells you something about how the Chinese felt about this particular species of tree.

The wood earned its reputation honestly. Other timbers rot, warp, crack, and surrender to beetles and time. Golden Nanmu does none of these things. Archaeologists have pulled logs from tombs sealed for two thousand years and found them looking as fresh as the day they were buried. The wood still smells faintly of citrus and spice. It still glows with that peculiar golden shimmer that gave it half its name.

Today, a single mature log can sell for more than three million dollars at auction. Museums guard fragments like they’re made of compressed diamonds. And anyone who’s ever worked with the wood will tell you it earned every bit of that reputation. The question isn’t whether Golden Nanmu deserves its legendary status. The question is how a tree managed to become more valuable than its weight in gold.

Table of Contents

The Tree That Emperors Couldn't Live Without

Pin

Pin Golden Nanmu / Photo courtesy Su Zhigang

Golden Nanmu trees, scientifically known as Phoebe zhennan, grow slowly in the misty mountain forests of southwestern China. These evergreens can take three hundred years to reach maturity, and they’re fussy about where they’ll grow. The trees prefer high altitudes, specific soil conditions, and the right balance of rainfall and fog. This pickiness made them rare even in ancient times.

Chinese emperors didn’t just like Golden Nanmu. They obsessed over it. The wood became the exclusive material for imperial construction projects during the Ming and Qing dynasties. Palace halls, throne rooms, imperial bedchambers, and even the emperor’s coffin had to be made from this timber. Owning Golden Nanmu furniture as a commoner could get a person arrested or worse.

The imperial monopoly created a bizarre situation where the wood became more tightly controlled than gold or silver. Government officials kept detailed records of every tree, every log, and every plank cut from the forests. Special teams of woodcutters worked under armed guard to harvest the trees. The penalty for stealing even a small piece was severe enough that most people wouldn’t risk it.

Why This Wood Refuses to Rot

Pin

Pin Golden Nanmu / Photo courtesy Unknown

The secret to Golden Nanmu’s immortality sits inside its cellular structure. The wood contains unusually high concentrations of natural oils and resins that act like a permanent preservative. These compounds are toxic to fungi, bacteria, and the wood-boring insects that normally turn timber into sawdust. The wood basically poisons anything trying to eat it.

Beyond the chemical defenses, Golden Nanmu has an incredibly tight grain structure. Water has trouble penetrating the surface, which means the wood doesn’t absorb moisture the way other timbers do. Without moisture, there’s no rot. Without rot, the wood lasts indefinitely. Beams installed during the Ming Dynasty still test as structurally sound today.

The wood also remains dimensionally stable across temperature changes. Other woods expand in heat and contract in cold, which creates cracks and splits over time. Golden Nanmu barely moves at all. A panel installed six centuries ago fits its frame as perfectly now as the day it was carved. This stability partly explains why imperial buildings constructed with this material have survived earthquakes, floods, and fires that destroyed structures made from other woods.

The Golden Glow Nobody Can Quite Explain

Pin

Pin Golden Nanmu / Photo courtesy Unknown

The name “Golden Nanmu” comes directly from the wood’s appearance. When freshly cut, the timber shows a warm honey color with subtle gold highlights. But the real magic happens over time. As the wood ages, it develops a deeper, richer glow that seems to emanate from beneath the surface. The effect intensifies in certain lighting conditions, making entire walls appear to shimmer.

Scientists have studied the optical properties of the wood and found something unusual. The cell structure refracts light in ways that create this internal glow. The natural oils in the wood also affect how light passes through the surface layers. The combination produces an effect that’s difficult to reproduce artificially. Some people describe it as looking at honey held up to sunlight.

This visual quality made the wood even more desirable for imperial use. Throne rooms built with Golden Nanmu panels created an atmosphere of warmth and luxury without requiring paint or gilding. The wood did the decorative work all by itself. Even today, museums that display Golden Nanmu artifacts often notice visitors stopping to stare at the way light plays across the surface.

The Scent That Lasts for Centuries

Walk into a room paneled with Golden Nanmu, and there’s a smell. Not overwhelming, but distinct. People describe it as citrus mixed with camphor, with hints of something spicy underneath. The remarkable thing is that this fragrance doesn’t fade. Wood installed six hundred years ago still releases the same scent when the surface is gently warmed or rubbed.

The aroma comes from volatile oils trapped in the wood’s cell structure. Unlike essential oils that evaporate quickly, these compounds release slowly over decades and centuries. The scent acts as more than just a pleasant addition. Those same aromatic compounds help repel insects and prevent fungal growth, adding another layer of protection to the wood’s already impressive defenses.

Imperial records mention the fragrance repeatedly. Emperors apparently enjoyed the smell so much that they insisted on Golden Nanmu for their private chambers. The wood created a naturally perfumed environment without burning incense or using other fragrances. Modern researchers testing ancient samples have confirmed that the scent remains remarkably consistent even after two thousand years of aging.

The Price Tag That Makes Gold Look Cheap

Current auction records show individual Golden Nanmu logs selling for prices that would make a diamond dealer nervous. A mature log measuring roughly three feet in diameter and twenty feet long can fetch between two and four million dollars. Smaller pieces, suitable for furniture making, still command prices of tens of thousands of dollars per cubic foot.

The astronomical pricing comes down to simple scarcity. True Golden Nanmu trees are now critically endangered in the wild. The Chinese government has banned all commercial harvesting of living trees. The only legal sources of the wood come from salvaged historical buildings, trees that died naturally, or logs recovered from river bottoms where they sank centuries ago during transport. Every available piece represents an irreplaceable fragment of a dwindling resource.

Wealthy collectors and museums compete fiercely for quality pieces. A single Golden Nanmu table can sell for more than a luxury apartment in many Chinese cities. The wood has become as much an investment vehicle as a building material. Some people buy pieces purely for speculation, betting that prices will continue climbing as availability decreases. They’re probably right.

How to Spot a Fake in a Market Full of Liars

The high prices have created a thriving market in fraudulent Golden Nanmu. Dealers sell ordinary cedar, camphorwood, or chemically treated pine as the real thing. Some fakes are crude, but others fool even experienced buyers. The problem has gotten serious enough that the Chinese government now requires certificates of authenticity for any wood claimed to be genuine Golden Nanmu.

Real Golden Nanmu has several telltale characteristics. The grain shows a distinctive ripple pattern called “water wave grain” that’s difficult to fake convincingly. The weight feels different too—heavier than most woods but not as dense as tropical hardwoods. The scent test helps, though experts warn that some counterfeiters have started treating fake wood with synthetic fragrances that smell similar.

The most reliable test involves examining the wood under magnification. The cell structure of true Golden Nanmu shows specific patterns that other species can’t replicate. Laboratory analysis can identify the characteristic oils and resins definitively. But these methods require expertise and equipment that most buyers don’t have access to. The counterfeiting problem has made buying Golden Nanmu nearly as complicated as buying fine art.

The Tombs That Preserved a Forest's Worth

When archaeologists opened the tomb of the Wanli Emperor in 1956, they found an underground palace built almost entirely from Golden Nanmu. The main burial chamber contained columns, beams, wall panels, and a massive coffin all carved from the precious wood. The tomb had been sealed for nearly four hundred years. The wood looked and smelled as fresh as if it had been installed the previous week.

This discovery wasn’t unique. Ancient Chinese nobles regularly used Golden Nanmu in tomb construction. They believed the wood’s imperishable nature would help preserve their bodies and possessions for eternity. The practice inadvertently created underground museums that protected huge quantities of the wood from the wars, fires, and deliberate destruction that wiped out so many historical buildings above ground.

Modern archaeologists face an ethical dilemma with these discoveries. The wood is priceless both as historical artifact and as raw material. Some tombs contain enough Golden Nanmu to supply the current market for years. But excavating tombs primarily to harvest building materials feels wrong to many researchers. Most ancient burial sites containing Golden Nanmu remain sealed and protected, their contents preserved but inaccessible.

The Craftsmen Who Still Know the Old Ways

A handful of master woodworkers in China still possess the knowledge to work with Golden Nanmu properly. These craftsmen learned their skills through decades of apprenticeship under older masters who learned from their own teachers in an unbroken chain stretching back to imperial workshops. The techniques aren’t written down anywhere. They exist only in the hands and minds of these aging specialists.

Working with Golden Nanmu requires different approaches than ordinary woodworking. The wood is harder and more resinous than most timbers, which dulls tools quickly. Traditional joinery methods that work for pine or oak don’t always transfer well to this material. The craftsmen use hand tools made from special steel alloys and sharpened to precise angles. Machine tools tend to burn the wood rather than cut it cleanly.

The knowledge these craftsmen possess is vanishing. Younger people have little interest in learning skills that take decades to master and offer limited employment opportunities. Most Golden Nanmu work today involves restoration and conservation rather than new construction. The number of people capable of this specialized work decreases each year. Some experts worry that within a generation, the traditional techniques will be lost entirely.

Why Modern Science Can't Reproduce It

Researchers have studied Golden Nanmu extensively, hoping to understand exactly what makes it so special. The goal is to either cultivate the trees more successfully or synthesize similar properties in other woods. Neither effort has succeeded particularly well. The tree remains as stubborn about being copied as it is about decaying.

Cultivation attempts run into the same problems that made the wood rare in the first place. The trees grow slowly even under ideal conditions. They’re susceptible to disease when young. And the wood quality varies significantly even within the same species depending on soil conditions, altitude, climate, and individual tree genetics. Trees grown in plantations often produce wood that lacks the full range of properties found in wild specimens.

Chemical treatments to make other woods more Golden Nanmu-like have produced disappointing results. Scientists can make wood more rot-resistant using various preservatives, but none reproduce the natural appearance, scent, or longevity of the genuine article. The specific combination of factors that makes Golden Nanmu special apparently can’t be replicated artificially, at least not with current technology. The tree keeps its secrets.

The Environmental Cost of a Legend

The centuries-long obsession with Golden Nanmu nearly drove the species to extinction. Imperial harvesting during the Ming and Qing dynasties removed most accessible mature trees. Later demand from wealthy collectors and furniture makers continued the pressure. By the late twentieth century, wild Golden Nanmu populations had collapsed to critically low levels across their native range.

Conservation efforts began in earnest during the 1990s when the Chinese government finally banned commercial harvesting of live trees. Protected forest reserves now shelter remaining wild populations. Researchers are working on cultivation programs, though success has been limited. The trees’ slow growth means that even if conservation efforts work perfectly, it will be centuries before new forests reach maturity.

The environmental situation creates a paradox. The wood’s extreme durability means that existing Golden Nanmu will last essentially forever if properly maintained. Buildings and artifacts made from this timber won’t need replacement. But the same properties that make the wood so valuable also drove humans to harvest it beyond sustainable levels. The tree’s greatest strength became the cause of its near-destruction.

The Future of the Immortal Wood

Golden Nanmu exists now primarily in museums, protected historical buildings, and the private collections of wealthy individuals. New supply comes almost entirely from salvage operations and occasional recovery of sunken logs from river bottoms. Some logs have been underwater for centuries and emerge still perfectly preserved, ready to be milled and used. But these discoveries are rare and becoming rarer.

The Chinese government treats remaining stocks of the wood as national treasures. Export restrictions prevent most Golden Nanmu from leaving the country. International trade in the wood is heavily regulated. Museums occasionally loan pieces for exhibitions, but the wood itself has become almost as difficult to move across borders as military equipment or radioactive materials.

Looking forward, Golden Nanmu seems likely to remain accessible only through existing artifacts and buildings. The wood visible in the Forbidden City and other historical sites represents most of what the world will ever see of this material. Those beams and panels will outlast the current century, the next century, and probably many more after that. The wood, at least, will endure. Whether the knowledge of how to work with it survives remains less certain.

FAQs

Not literally forever, but close enough. The wood has been documented lasting over 2,000 years with no significant decay. Its natural oils and tight grain structure prevent rot, insect damage, and moisture absorption that destroy other woods.

Extreme scarcity drives the price. The trees are now protected and can’t be legally harvested. All available wood comes from salvage, making supply extremely limited while demand from collectors and museums remains high. A single log can cost $3 million or more.

Authentic Golden Nanmu has a distinctive water-wave grain pattern, weighs more than most woods, emits a subtle citrus-camphor scent, and develops a golden glow. Lab analysis of cell structure and oil content provides definitive identification.

Very few wild trees remain, and they’re protected in special reserves. The species is critically endangered. Conservation programs are attempting cultivation, but the trees grow extremely slowly—taking 300 years to reach maturity.

The wood resists water damage far better than ordinary timber. Even if submerged for centuries, it emerges intact. Minor damage can be repaired by specialized craftsmen, though finding someone with the traditional skills is increasingly difficult.