Pin

Pin Gunnar Ries, CC BY-SA 2.5, via Wikimedia Commons

Most people think of continents as clear-cut landmasses, but nature doesn’t always follow our maps. There’s an invisible line in Southeast Asia that separates animals in a way that doesn’t make sense at first glance. This is the Wallace Line, a biological boundary that puzzled scientists for years.

If you look at a map, Indonesia seems like one big group of islands, so you’d expect the same animals everywhere. But that’s not the case. On one side, you have kangaroos and cockatoos, animals you’d associate with Australia. Cross the Wallace Line, and suddenly, you’re in the land of tigers and monkeys. How does that happen? There’s no physical wall stopping animals from moving, yet the species on each side barely mix.

This isn’t just some random quirk of nature—it’s a deep, historical divide that tells the story of how continents drifted apart and shaped life in ways we rarely notice.

Table of Contents

Alfred Russel Wallace: The Man Who Saw the Divide

Pin

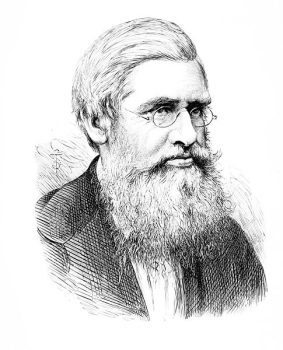

Pin Popular Science Monthly Volume 11, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Before airplanes and GPS, explorers had to travel by boat, foot, and sheer curiosity. One of those explorers was Alfred Russel Wallace, a British naturalist who spent years in the 1800s traveling through the Malay Archipelago (modern-day Indonesia and surrounding areas).

Wallace wasn’t just collecting pretty butterflies—he was documenting everything he saw. And one thing stood out. As he moved between the islands of Bali and Lombok, he noticed a sudden change in wildlife. On one island, he’d see species like orangutans and elephants, similar to what he’d expect in Asia. But just a short distance away, he found marsupials, like tree kangaroos, which were more like the wildlife of Australia.

This wasn’t a small difference. It was a dramatic shift, and it didn’t make sense unless there was an invisible boundary that separated these two regions. Wallace drew a line on the map, unknowingly marking one of the most important discoveries in biogeography.

Why the Wallace Line Exists

Pin

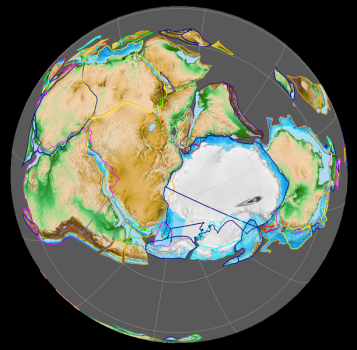

Pin Fama Clamosa, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

At first glance, the Wallace Line seems strange. There’s no ocean trench or mountain range stopping animals from crossing. So why don’t species mix more? The answer goes deep into Earth’s history.

Millions of years ago, the continents weren’t where they are today. Australia, Antarctica, South America, Africa, and India were all connected in a supercontinent called Gondwana, while Asia was part of a separate landmass, Laurasia. Over time, these massive land pieces drifted apart.

Australia and the islands near it carried their own set of animals, like marsupials. Meanwhile, Asia had its own evolution going on, with placental mammals like tigers and elephants. Even when the islands of Indonesia formed, deep underwater trenches remained, preventing easy migration. That’s why even though Bali and Lombok are so close, their animals never mixed—because they were never connected by land.

The Wallace Line isn’t just a random division. It’s a leftover trace of how continents shaped the life we see today.

How the Wallace Line Affects Wildlife Today

If you step onto the islands around the Wallace Line today, you’ll still see the same strange divide that Wallace noticed over 150 years ago. The animals on each side of the line haven’t changed their habits—they still stick to their own territories.

On the Asian side, you’ll find creatures like tigers, rhinos, monkeys, and elephants. These are classic Asian species that have spread across the mainland and onto nearby islands like Sumatra and Borneo.

But take a short trip across the Wallace Line to islands like Sulawesi or Lombok, and suddenly, it feels like you’ve landed in Australia. You’ll see marsupials like tree kangaroos and the bizarre-looking babirusa (a wild pig with tusks that curve backward). No tigers, no elephants—just completely different species.

This isn’t just an old historical quirk. The Wallace Line is still actively shaping where animals live, proving that geography and evolution are deeply connected in ways most people never realize.

The Wallace Line vs. Human Boundaries

People love drawing borders on maps, but nature doesn’t care about political lines. The Wallace Line, however, is a real natural boundary—one that has existed long before humans started mapping the world.

If you look at modern countries like Indonesia, you’ll see that they span both sides of the Wallace Line. That means Indonesia isn’t just culturally diverse—it’s biologically diverse too. The western islands, like Sumatra and Borneo, share wildlife with mainland Asia, while the eastern islands, like Sulawesi and Lombok, have creatures more similar to Australia.

Humans have tried to ignore nature’s boundaries. Zoos, conservation programs, and even illegal wildlife trade have moved species across the line. But even with modern technology, the Wallace Line still holds strong. Animals that evolved separately for millions of years don’t easily adapt when placed on the other side. It’s a reminder that while people can redraw maps, the deeper forces of evolution and geography are much harder to erase.

What Happens When Species Cross the Wallace Line?

Nature has a way of keeping things in balance, but when humans interfere, things get messy. The Wallace Line has acted as a natural barrier for millions of years, but what happens when animals cross it?

Some species have been deliberately or accidentally introduced across the line. For example, the Javan rusa deer, originally from the Asian side, has been introduced to islands past the Wallace Line, including New Guinea and northern Australia. Since these areas never had large grazing animals before, the deer have caused serious ecological damage by outcompeting native species.

On the flip side, some Australian species, like certain birds and reptiles, have naturally expanded their range westward in recent years. Climate change and human activity are making these once-rigid boundaries blur. But evolution doesn’t work overnight. Just because an animal moves across the Wallace Line doesn’t mean it will thrive. Some simply can’t adapt to the competition and environment of their new territory, reinforcing why the Wallace Line has remained a strong divide for so long.

The Wallace Line and Conservation Efforts

Understanding the Wallace Line isn’t just about history—it plays a huge role in protecting wildlife today. Conservationists use this invisible boundary to guide their efforts, making sure ecosystems stay balanced.

For example, when setting up protected areas and wildlife reserves, scientists consider the Wallace Line. They know that animals on one side have evolved separately from those on the other, so mixing them could cause problems. Breeding programs, reforestation efforts, and species reintroduction plans all take the Wallace Line into account.

Unfortunately, deforestation and human expansion don’t follow natural rules. As people build roads, plantations, and cities, they break up habitats, making it easier for invasive species to cross the line. If too many non-native species enter a new environment, they can wipe out the original wildlife that has lived there for thousands of years.

That’s why conservationists fight to protect the Wallace Line—not as a physical barrier, but as a key to keeping Southeast Asia’s biodiversity intact.

The Wallace Line’s Impact on Science and Evolution

The Wallace Line isn’t just a cool geographical feature—it helped shape how we understand evolution. Before Wallace made his discovery, scientists were still debating how species formed and spread. His observations added critical evidence to the theory of evolution.

Wallace’s findings supported the idea that species evolve based on their environment and geographic isolation. The stark contrast in wildlife on either side of the line showed that evolution isn’t random—it follows clear patterns based on geography. This was one of the key insights that helped Darwin refine his own theory of natural selection.

Today, the Wallace Line is still used in studies on biogeography, genetics, and conservation. Researchers study why some species never crossed the line, while others have slowly moved over. It also helps scientists predict how climate change and habitat destruction might impact different species in the future.

Wallace may not have had today’s technology, but his discovery remains one of the most important in evolutionary science.

How the Wallace Line Influences Modern Travel and Tourism

For travelers, the Wallace Line is more than just a scientific concept—it’s a chance to see two completely different ecosystems in one trip. Indonesia, the country that straddles this invisible divide, has become a hotspot for eco-tourism because of it.

If you visit Sumatra or Borneo (west of the Wallace Line), you’ll find rainforests filled with orangutans, elephants, and tigers. It feels like a tropical version of Asia, with dense jungles and massive rivers. But take a short flight to Sulawesi or the Lesser Sunda Islands (east of the Wallace Line), and suddenly you’re in a different world. Marsupials, strange-looking creatures like the babirusa, and birds that seem straight out of Australia take over.

For wildlife lovers, the Wallace Line creates an incredible contrast. It’s one of the only places on Earth where you can see two evolutionary worlds collide—just by hopping from one island to the next.

Why the Wallace Line Still Matters Today

The Wallace Line isn’t just a relic of the past—it’s a reminder that geography and evolution are deeply connected. Even in today’s world, where humans can travel anywhere, nature still follows its own rules.

Understanding the Wallace Line helps scientists, conservationists, and even everyday travelers appreciate why biodiversity is so unique across the world. It shows that evolution isn’t random—it’s shaped by millions of years of separation, environment, and adaptation.

But this natural divide is under threat. Deforestation, climate change, and human activity are slowly breaking down the barriers that kept these ecosystems apart. Some species are being pushed out, while others are invading new territories. The question is: what happens if the Wallace Line disappears?

The answer could reshape entire ecosystems. That’s why studying and protecting the Wallace Line isn’t just about history—it’s about preserving the future of wildlife before it’s too late.

This invisible line has defined species for millions of years. The real challenge now is making sure it still exists for generations to come.